Charlotte is crying and she looks up at me with big watery eyes. She says something really quiet. What? says Kate. Say it, Charlotte. You didn’t have a problem saying it ten minutes ago. Tell her. Charlotte cries and looks up at me and she is like a bird I saw once with a broken wing, hopping around and dragging the wing. Said, Charlotte sobs. Said Mommy fucks Aaron. Kate grabs Charlotte’s arm and forces the bar of soap into her mouth. Dirty, bad, lying girl! Kate yells. Why would you say that to Daddy? I’m confused and scared. Kate looks at Charlotte, sitting on the toilet with the bar of soap jammed in her mouth and says, Now I’m going to be late for work. And Daddy’s never going to talk to you again. She slams out of the bathroom and I can hear her in her bedroom, stomping around and banging her closet door. I take the soap out of Charlotte’s mouth and she just looks at me, tears spilling out of her eyes. I pick up her Bugs Bunny toothbrush and squirt green toothpaste on it, help her brush her teeth to get the soap taste out of her mouth. She spits out the foam and I put more toothpaste on the brush, tell her to brush again like a big girl.

–from “Casey and Finnegan,” by Chandra Mayor

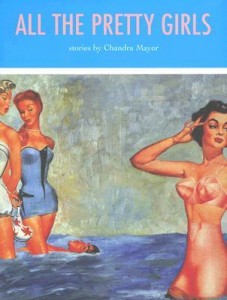

I think Chandra Mayor is one of those writers who people love to project lots of meaning onto—“Winnipeg’s punk poetess” I think I saw a journalist call her once. The publisher write-up on the back of All The Pretty Girls—Chandra’s gorgeous, murky, raw, painful, beautiful collection of short stories—has some of the more melodramatic copy of the type. “These are young women who roll pennies to buy toilet paper and roll their own cigarettes, who watch the mail for the welfare cheque and watch their boyfriends and lovers out of the corners of their eyes…Mayor insists that all girls are pretty girls…”

Actually, I’m pretty sure Chandra doesn’t “insist” much of anything in the book. And after two re-reads I don’t remember any scenes of rolled pennies or cigarettes, though I suppose they could’ve been single lines I missed. But regardless, I always find it all somewhat misleading—there’s no stated manifesto in her writing, and the poverty is real, entrenched, rarely dramatized, it just…looms behind everything. Some of the women have kids, some don’t. Some of them date girls, some haven’t yet figured out they should be dating girls. The protagonists—to me—are somewhat interchangeable in how they feel and act and react to stuff but I love that, honestly—most of the writers I’m drawn to seem to give all their characters the same brain. They don’t get out, shit never gets solved. My favourite story is the last one, “A Boy With Pink Lipstick” quoted below, about a girl with an asshole boyfriend who finds out she’s pregnant, considers whether to have another abortion, birth the child, or throw herself down the stairs. Save one story, “Parquet,” and the dreamy panoramic “Carly’s Hippie Mofo Shit: Mixtape Revisited,” none of these girls finish the story very much ahead from where they started. Which is very Winnipeg I suppose, or at least certain sectors of it: Poor people in unhappy stasis, little changing.

The illusions of all the girls that looked like Carly, all the girls that looked like me, all the ones who believed that we’d already seen both sides of everything. There’s a woman waiting for me at home, a woman who loves me but finds that after ten years I’m not really what she wants at all. There’s a child, a girl with a sketchbook and great pools of light and shadow in her eyes, walking the tightrope through her own teenage years. There’s a woman in an upstairs apartment down the street, listening to records late into the night. All those bruised and laughing girls, smoking cigarettes and playing broken guitars in downtown apartments who feel the things that they lose pull at their fingertips, every day. It still hurts and sparks and lingers, in the way that only ghosts can. What I have now is substantial and thrumming with blood, my own self sitting in my familiar body, my heart softer and stronger, less mysterious to me. A ticket in my pocket, a plane to catch. The fragile wisps and steel edges of hope, well-worn and comfortable in my cupped hands.

–from “Carly’s Hippie Mofo Shit: Mixtape Revisited”

“It’s really hard for people to get too big for their britches in this city,” Chandra said, in one of very few recorded interviews I’ve ever found from her. Truth. I spent my childhood in between rural Manitoba and the Winnipeg that Chandra writes about, at about the 90s-ish time All The Pretty Girls takes place. I found a copy of the book in Montreal, of all places, in a used English bookstore in 2013, days before going in for bottom surgery, in mid-October when fall was turning cold. I read it all the next week, drugged and bleeding in the care clinic, shuffling between bed and the kitchen area. The clinic was beside a river and the sky was mostly grey.

“It’s really hard for people to get too big for their britches in this city,” Chandra said, in one of very few recorded interviews I’ve ever found from her. Truth. I spent my childhood in between rural Manitoba and the Winnipeg that Chandra writes about, at about the 90s-ish time All The Pretty Girls takes place. I found a copy of the book in Montreal, of all places, in a used English bookstore in 2013, days before going in for bottom surgery, in mid-October when fall was turning cold. I read it all the next week, drugged and bleeding in the care clinic, shuffling between bed and the kitchen area. The clinic was beside a river and the sky was mostly grey.

My mother wasn’t like Chandra’s women (my father kind of was), but the beauty and lack of pretension and murkiness and overwhelming pathos of All The Pretty Girls reminded me of my own poor and depressed childhood in that cold unrelenting city more than anything else ever has, and for those two equal reasons I cried and felt balmed, as I have on every read since. And that is all there is.

I went to the park, sat in the sticky thrumming green grass with the kids and the moms and buzzing crawling insects. I waited until I saw Mark take off down the street to the Albert, hours later. I went up to the apartment, changed my clothes, stuffed a bunch of apples in my canvas bag, and went back to the park, the far side where I usually didn’t sit. My hands clenched my skirt and left wrinkled sweat stains on the yellow silk. I was back in my own clothes, fabric made from kisses and flicks of the tongue, tiny frayed straps that skimmed my shoulders, the camisole falling around my body like broken butterfly wings. I smoked cigarettes and stared at the blue sky until my mind was blank, reptilian, thick and clotted with knots and blood and breath that didn’t move all the way through. I heard a kid that might have been Sky, with some guy that might have been Don, but I didn’t bother looking, just curled myself tighter against the ridges of a thick scarred tree. I sat there all night, watching the streetlights, wishing for stars.

–from “A Boy With Pink Lipstick”

Casey Plett wrote the short story collection A Safe Girl To Love and wrote a column on transitioning for McSweeney’s Internet Tendency. She has written for Rookie, The Walrus, The New York Times ArtsBeat, and other publications. Twitter @caseyplett.