INTERVIEW BY BRETT JOSEF GRUBISIC

INTERVIEW BY BRETT JOSEF GRUBISIC

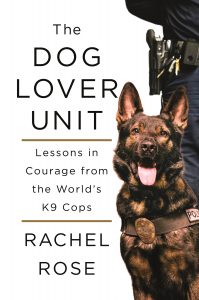

When her wife encouraged her to take on a brand new kind of writing project, Rachel Rose felt real trepidation while sensing glimmers of possibility too. Five years (and countless hours of research, high speed chases, and nursing sore body parts) later, The Dog Lover Unit has hit shelves. More than a factual book about a highly visible yet little-known world (about which, never the less, everyone has an opinion), Rose’s book is thoughtful, revealing, and informative. As a DIY investigative journalist who’s also Vancouver’s keen-eyed poet laureate, Rose takes her looking-behind-the-scenes duties seriously. She also inserts more than a few of her own political viewpoints and evolving personal responses along the way.

Brett Josef Grubisic: As a self-described “stressed-out mom of three young kids” and “dissident leftie feminist poet,” a project taking five years that would lead to you hanging out with Second Amendment advocates, experiencing adrenaline dumps during high-speed chases, and volunteering to get attacked by police dogs seems wildly improbable.

Before you began the research and writing, how did you initially envision the book? In what ways did it change along the way?

Rachel Rose: Honestly, I had no clear initial vision of the book, or even if what I was doing would become a book, though I hoped it would. So why did I spend years of my life obsessed with police dogs, especially considering my background? The short answer is, I was curious. Part of my process as a writer has always been what I now think of as tracking: I find something I don’t understand, something astonishing or infuriating, frightening or incredible, and I start writing to make sense of it, following wherever the scent leads. It is a deeply satisfying and deeply inefficient approach, to explore the world in this intuitive way. Often, these quests don’t become books, or haven’t yet—like the work I’ve done with hospice, and with martial arts training. But I trust my tracking sense, my writer’s intuition. It knows more than I do, and it is how I move through the world.

I wrote, and shed, several books along the way to writing this one. One important shift was to move beyond Canada, and look at policing from a cross-cultural perspective, including the USA, Paris, and London. I would have loved to do more of that, actually, and spend time riding with K9 teams in Japan and Mexico, among other places. (Perhaps there will be a sequel!)

BJG: In The Dog Lover Unit you discover an unexpected affinity between yourself as a poet (who writes, in part, “to make order out of chaos”) and the “rough cops and their dogs” with whom you spent so many days. What had you expected to feel when you began riding in police cars and meeting the dogs’ handlers, and what did you find that wowed you?

RR: I had expected to feel awkward and shy, which I definitely did, but my bigger worry as an introvert was not to have anything to talk about when stuck in a truck with a stranger from a very different world than my own. That worry turned out to be needless. Almost without exception, the cops I rode with were natural storytellers, and all I had to do was listen, take notes, ask questions. These were men and women who carried so many amazing stories from years on the job. Police officers, doctors, paramedics—their lives are filled with dramatic events, trauma and adventures, that have nowhere to go. I gave them a place to put their stories.

BJG: For me, one of the distinctly satisfying and rewarding aspects of your book was the decision to splice together diverse elements. There’s reportage and your fish-out-of-water experiences with police units and criminal offenders. And there’s your taxing at-home challenges as a wife and parent with your traumatic experience as a crime victim when you were much younger. For anyone, personal revelations like these can put them in a position of feeling or being vulnerable. How did the process of writing lead you to the autobiographical inclusions in what could have otherwise been a journalistic account in which the writer becomes a “neutral conduit” for the story she witnesses?

RR: While the vulnerability is a very real issue, I didn’t want to be a neutral conduit. I am drawn to narrative where the writer is implicated in the subject matter. I am grappling with where I am implicated in all of these issues; why should I hide that interesting process from my reader? How much to reveal is always a challenge for a memoirist. I wrote the book with more of my story initially. I took almost all of it out in a later draft. The draft that was finally published tells some of my story in the context of what I discover or see while out with the dogs. I think it’s important to read the book in context, as my own personal story unfolds as I was on the road. I became curious about what police officers actually have to do, including their job of being first responders to victims of crime. That led me to interview victim services workers and talk to them about their role, and how things have changed, and have not changed, for victims, and I tell my own story in that context.

BJG: Other than being attacked by dogs a few times and having to wear a Frenchman’s used jockstrap, what were the biggest personal challenges for you during the researching segments of your project?

RR: Personal challenges included learning to be persistent, and to ask strangers repeatedly for things. If I hadn’t overcome that obstacle, the book would not exist. There are exceptions, and some departments are more open than others, but as a rule, police officers generally do not want to talk to journalists, even poets posing as journalists.

I had to get comfortable with being lost. I got lost so much trying to meet up with the cops. I know that most people have GPS, but I don’t, and I don’t want it—I love my old car and I don’t use my phone for much beyond phoning, and in any case it has this tendency to not work when I most need it. It was stressful, and perhaps it was an unnecessary stubbornness on my part, but I became more confident that I would eventually figure out where I needed to be.

Also true, I was struggling and a little bit lost in my own life. I think a lot of moms can relate to this. My days belonged mostly to other people. I love my family so much, but my world felt as if it had become small. So I challenged myself to make my world bigger by stepping into the world of these K9 teams, literally following in their footsteps as they trained.

I have neither the personality nor the physical toughness to be a dog handler, but this is as close as I will get, and as much as it was a challenge, it also brought me back to a part of myself that used to be outside with my dogs and my horses, roaming and free. That was great.

But for sure the biggest challenge was dealing with fear. Most of the ride-alongs I did, there were moments (as you will read in the book) where I was legitimately terrified. Nights before ride-alongs, I’d feel an edge, knowing that I didn’t know what would happen, and sometimes driving there, I’d feel these flashes of reluctance to go—the sleep deprivation, the physical discomfort, the fear. But those were only flashes—far more was this feeling of unbelievable excitement that I could tag along with these K9 teams, that I could play fetch and track with these dogs.

BJG: At the end of your book you remark, “There is one story about cops in my leftie circle: they are brutal, power-hungry, racist thugs … I fear that people in the arts community, who might have supported my work and the spirit behind it, will not support this work. People on the right politically will likely not support me, either personally or ideologically. And yet, here I am.” Please tell me about the emotional and philosophical and moral meaning of this “here I am.”

RR: Fyodor Dostoyevsky wrote, “The degree of civilization in a society can be judged by entering its prisons.” I would add to Dostoyevsky’s observation that a society can also be judged by the way in which it is policed. So policing becomes a way of looking at society. It encompasses so much: gender roles, human rights, class, race and power, weapons and violence, victims, criminals, authority, compassion, safety nets (or lack thereof).

Historically, writers trend more or less toward being voices for those who are oppressed, voices for the individual against the state, the underdog and the abused. This fits with my own personal values, and indeed, as poet laureate I have worked as an advocate for refugees and low-income people who are dealing with food insecurity; I have supported imprisoned writers through PEN campaigns; and I have worked for decades against state abuse of human rights.

But I also believe that a writer’s job is to investigate. “I wonder what would happen if I negotiated my way into a pre-med anatomy course?” I asked myself, and my first book, Giving My Body to Science, was the answer. This curious impulse is the truest thing about my work.

Within me exists a permanent tension between the judgmental, activist self, the utopian idealist who wants to make, to force, really, the world to become a better, more humane, humanitarian place, and the writing self, who looks at things—all things—without judgment, who sees how interconnected we all are, and who above all observes, not the way things should be according to me, but the way things are, with all their complications and contradictions.

Activists have answers. That’s why we can be insufferable. We know how the world should be, and we want to compel it to change. But I write from a place of not having answers, only the questions that lead to a quest. My writing is born of not-knowing, of trying to figure something out, whether it is how love and marriage fit together or why some of the best parts of our humanity emerge only in relationship with non-human animals. My writing is my own search for deeper understanding, made public.

BJG: You mention that you’ve been “changed so much” by your time with the dogs. Now that your project has become a book and your late nights in police cruisers has ended, what lasting impression have the dogs and dog units made on you?

RR: To never give up, to keep fighting even when it seems to be hopeless. Also, to fight smart: to know your tactical options to resolve your situation. Don’t keep doing the thing that isn’t working. Change course, try something else, think things through and take action in a different way. This is as true to tracking a criminal as it is to trying to save your own life during a knife fight as it is to overcoming fear of failure as a writer.

Imagine if writing programs offered courses in perseverance and overcoming obstacles, the way police academies offer courses in tactical options. Most of what stops creative people is not lack of talent: it’s not knowing a way to get through the roadblocks.

This is not news, but it was knowledge I needed at the time. When you are going through hard times, sometimes the way to get through is counter-intuitive: to do something even harder, but something very different. I guess I learned that from both the dogs and their handlers: the dogs don’t like to give up when they are on a track. There’s a point where they will, where they get physically tired, but when they trust their handlers, they work as a team, and they persevere. To see what every officer has to go through to even get into the K9 unit, and what they face on the road—it is inspiring to be around that kind of drive and energy and willingness to commit 100 percent. I learned some of that grit just being in their company, and I think it will serve me well.

A UBC prof, Brett Josef Grubisic has written fiction including the novels The Age of Cities and This Location of Unknown Possibilities. His current novel project is set in a small BC mill town in late 1980; From Up River, and One Night Only tells the up-and-down tale of two sets of teenage siblings who form a New Wave cover band.