This article is part of the Queer Press Profiles series by DJ Fraser

Even before its launch in the summer of 2015, Dagger Imprints was a community venture, responsive to the climate in the BC publishing industry, and run by a few extremely dedicated employees of Vici Johnstone, owner of Caitlin Press. The name of the small imprint from Caitlin, entirely dedicated to the writing of queer women, was chosen by the community surrounding the press that operates out of Sechelt on the Sunshine Coast. Not only is the name a reference to homophobic language and judgment from earlier in the twentieth century, it also is a cute in-joke dedicated to the publishing industry, as a dagger is also a typographic glyph.

The name of this small arm of Caitlin is part of a historical project of reclamation, which recognizes dagger as a slur, and the complex history in the queer community of necessary redemptions of language that has hurt us, or that continues to press its sharp sides against our skin, thick as it is. Johnstone at first recoiled from the sound of the suggested name—she remembered the revulsion and virulent homophobic sentiment she had experienced when she first came out in the late seventies—but Johnstone had to admit it sounded right, that it sounded like the right kind of name for this project of reclamation.

The idea of a dagger’s imprint, points or marks made with such a powerful weapon, reminds us that even heavy tools can be worked with precision and delicacy.

Dagger Editions, or something like it, had been a brainchild of Johnstone’s since before she bought Caitlin Press, a company committed to the stories of rural outliers. Adopting the mandate of “where urban meets rural,” Johnstone began publishing stories of the BC Interior and around the South Coast.

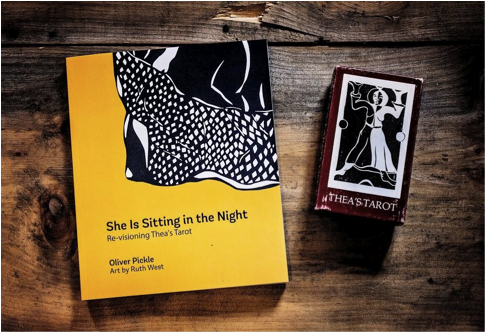

By the time the press was launched, there were already a few projects in the works: Dagger already has some heavy hitters of Canadian queer women writers, including Betsy Warland, Nicola Harwood, Arleen Paré, and other burgeoning talent like Leah Horlick and Andrea Routley.

By the time the press was launched, there were already a few projects in the works: Dagger already has some heavy hitters of Canadian queer women writers, including Betsy Warland, Nicola Harwood, Arleen Paré, and other burgeoning talent like Leah Horlick and Andrea Routley.

By specifically naming the project, and creating a rare space for works by queer-identified women to shine, Dagger Editions offers to its readers a roster of voices and a range of experience that escapes the mainstream publishing world.

Through this curation of queer women’s voices, the team at Dagger Editions hopes to foster emerging writers and uncover a greater wealth of Canadian women’s stories from the intersection of the rural and urban, stories from the outskirts and border zones of queerness in Canada. Although there is a large amount of diversity in the Canadian publishing industry, and many queer presses among them, there is only Dagger when it comes to showcasing the voices of queer-identified women in Canada. With the full support of fellow community presses like the infamous (unfortunately defunct) Press Gang and the eminent Arsenal Pulp Press of Vancouver, the imprint is off to a running start.

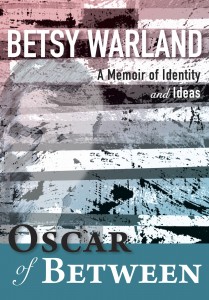

The press is providing a new and much-needed space for queer women’s voices in Canada, but it is not only in our ever-expanding libraries that we’ll see change: as part of the publishing mandate in Canada, all books have to be registered with Library and Archives Canada in order to create a master list of all published works in the country. When Betsy Warland’s book exploring gender non-conformity was erroneously listed under the category of “transsexual,” it was clear that, although times have changed, the language of the heteronormative, cisnormative world is still barely adequate to describe the creative outpouring of the queer community, let alone voices that dare transgress the gender binary.

The press is providing a new and much-needed space for queer women’s voices in Canada, but it is not only in our ever-expanding libraries that we’ll see change: as part of the publishing mandate in Canada, all books have to be registered with Library and Archives Canada in order to create a master list of all published works in the country. When Betsy Warland’s book exploring gender non-conformity was erroneously listed under the category of “transsexual,” it was clear that, although times have changed, the language of the heteronormative, cisnormative world is still barely adequate to describe the creative outpouring of the queer community, let alone voices that dare transgress the gender binary.

In the end, after much work, Warland’s book was listed under “gender identity.” Not an exact fit, but closer to an understanding of gender non-conforming folk who feel a connection with liminal states of gender expression.

This is only one of the ways in which queer presses are actually refiguring the landscape of the publishing industry in order to create spaces in which queer voices are not only recognized, but respected, and in which stories from queer women in Canada can represent a shifting landscape of urban, rural, and queer identity that is finally being looked at in literature as an essential and vital part of a dialogue about the Canadian terrain of life and art, creation and experience.

“We’ve come so far now,“ Johnstone said, adding that people, even outside of the queer community, can now access the language and “say the words” that mean so much. It’s time to set these glyphs to a page, making impressions as we go.