Reviewed by Vivek Shraya

Beldan Sezen’s new graphic novel, Snapshots of a Girl, opens with this definition of coming out: “The decision to step out of the unseen, the unspoken, the unnamed. Telling others, loved ones, dear ones, about one’s so-called ‘sexual preferences’ … something you know will disturb the polite agreement of a shared silence.”

Perhaps one of the pitfalls of more queer representation in media is a displaced sense of refined gaydar, which in turn has heightened the insidious practice of outing queers. And it’s not just straight people who engage in this practice. I always dread and rage at the glib tweets from queers on Twitter after a celebrity comes out, usually along the lines of “it’s about time” or “this is not news” or “duh.” Somehow we forget how disturbing it is to discover something atypical about yourself, something you know will disturb the people around you too. We forget what it means to feel as though love itself, supposedly the one thing humans need most, is at stake. We forget that coming out is a personal, private journey that we all have the right to explore and to facilitate. We forget that coming out is a choice—and for many, not a safe or necessary choice.

Snapshots is a beautiful reminder of the vulnerability in coming out not just to others, but also to oneself. “The Denial Years” shows the nameless protagonist awkwardly navigating various boyfriends, only to be perpetually disappointed. There is similar awkwardness and disappointment in her first experiences with women too. A scene where she has just had sex with her crush ends with: “I left feeling as if I had asked for the moon and the very moment I held it in my arms I didn’t know what to do with it.” Sigh. Isn’t this precisely what it feels like to be loved or desired when you aren’t ready to be?

The chapters titled “Coming out … To My Mother—Part Two” and “Coming out … To My Mother—Part Three” highlight the ways that, unlike how it’s portrayed, coming out is not quite a destination but rather—frustratingly—a perpetual action. This is especially true for queer people of colour, in that we must navigate cultural differences and obligations on top of being queer. Many queer people of colour don’t have the Lifetime movie moment with our families rushing to embrace our queerness. Instead, they sometimes skirt around our sexuality, like when the protagonist’s mother says that her real discomfort is the protagonist’s usage of rude language in her books.

The chapters titled “Coming out … To My Mother—Part Two” and “Coming out … To My Mother—Part Three” highlight the ways that, unlike how it’s portrayed, coming out is not quite a destination but rather—frustratingly—a perpetual action. This is especially true for queer people of colour, in that we must navigate cultural differences and obligations on top of being queer. Many queer people of colour don’t have the Lifetime movie moment with our families rushing to embrace our queerness. Instead, they sometimes skirt around our sexuality, like when the protagonist’s mother says that her real discomfort is the protagonist’s usage of rude language in her books.

But there can still be small gestures of acceptance and tenderness with our families, like when the protagonist comes out to her father in the car, and after a short discussion he offers her some gum. That gum might seem ordinary, silly, or even condescending to some readers, especially after her confession, but for me, that gum is precious. That gum says, “I love you.”

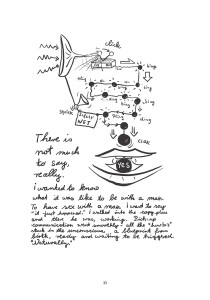

Stylistically, Snapshots features a variety of fonts and sketchbook-style illustrations, which makes for an unpredictable, captivating read and sets a new standard for the modern journal. Sezen also doesn’t shy away from sexual content—talking vaginas? Check! Cartoon cocks? Check! This is refreshing to see in a book that will certainly appeal to young readers, as well as fans of Elisha Lim and Alison Bechdel.

Towards the end of the book, Sezen tackles labels, often another aspect of coming out: “No one wants to be labeled. You know what? i do. What i don’t like is to be judged by my labels.” This distinction between disliking how labels are interpreted versus disliking labels themselves is important. Labels tend to have a bad reputation, particularly from those with privilege. I regularly hear statements like, “Why do we need so many labels? Aren’t we all just human?” For queer and trans people, finding new ways to describe ourselves can be crucial when so many of us have spent lifetimes trying fit into the names that were wrongly assigned to us. Labels also give us a means to name oppression; calling ourselves “human” doesn’t allow us to address our experiences of homophobia, biphobia, and transphobia. As the protagonist says, “By saying i am butch, i am in charge, and i can handle the countless looks, insults, and attacks often caused by my visible ‘nonconformity’ to prescribed gender roles.”

Towards the end of the book, Sezen tackles labels, often another aspect of coming out: “No one wants to be labeled. You know what? i do. What i don’t like is to be judged by my labels.” This distinction between disliking how labels are interpreted versus disliking labels themselves is important. Labels tend to have a bad reputation, particularly from those with privilege. I regularly hear statements like, “Why do we need so many labels? Aren’t we all just human?” For queer and trans people, finding new ways to describe ourselves can be crucial when so many of us have spent lifetimes trying fit into the names that were wrongly assigned to us. Labels also give us a means to name oppression; calling ourselves “human” doesn’t allow us to address our experiences of homophobia, biphobia, and transphobia. As the protagonist says, “By saying i am butch, i am in charge, and i can handle the countless looks, insults, and attacks often caused by my visible ‘nonconformity’ to prescribed gender roles.”

Snapshots of a Girl is an inspiring and sometimes wrenching story about a girl learning to take charge—of her body and her desires—not despite her detours and downfalls, but through them.

Belden Sezen, Snapshots of a Girl (Arsenal Pulp Press, 2015). Paperback, 152pp., $17.95

Vivek Shraya is a Toronto-based artist working in the media of literature, music, performance, and film. Vivek’s body of work includes 12 albums, four short films, and three books, which have been used as textbooks at several post-secondary institutions. Her debut novel, She of the Mountains, was named one of The Globe and Mail’s Best Books of 2014.

Vivek is a three-time Lambda Literary Award finalist, a 2015 Toronto Arts Foundation Emerging Artist Award finalist, and a 2015 recipient of the Writers’ Trust of Canada’s Dayne Ogilvie Prize Honour of Distinction. Both Vivek’s debut collection of poetry, even this page is white, and her first children’s picture book, The Boy & the Bindi, will be published by Arsenal Pulp Press in 2016. Her book on recording artist M.I.A. will be published in 2017 by ECW Press, as part of their Pop Classics series.