Jo wakes up with a lump on her throat. Not in, but on.

She sees it first in the bathroom mirror as her face fades into view through the steam from the shower. It’s about the size of a marble, gelatinous in consistency. When she touches it, she feels it move slightly beneath the skin.

Lucille comes into the bathroom, blurry-eyed and dishevelled from sleep. “Good morning, wife,” she says, and deposits a kiss on the top of Jo’s head. This is almost a joke, born out of the early days of their marriage, when the official title still felt thrillingly strange. They had taken every opportunity to say the word wife, back then, revelling in how fresh and awkward it felt to wear, like new shoes. These days the shoes are broken-in, the leather scuffed and the soles comfortably flattened, but they still say it whenever they can, out of habit.

“Good morning, other wife,” Jo replies. She turns, baring her throat. “What do you think of this?”

Lucille leans forward to examine the lump. Her foul morning breath is warm on Jo’s skin. “Hmm,” she murmurs. The tip of her ring finger presses questioningly. “Swallow for me.”

Jo obeys. She feels the lump squirm vigorously under Lucille’s touch, as though animated by some strange internal engine.

“It might be a cyst,” Lucille says, but doubtfully. She’s a doctor, and it’s her job to know such things. How lucky of me, Jo often thinks, to have married a doctor. “Or just a big zit, maybe. Let me get a needle. I’ll lance it for you.”

She pads downstairs and returns with a needle from her sewing kit. After carefully sterilizing it with rubbing alcohol, she sets the point of it to Jo’s throat. The lump quivers like a cat. Gently, carefully, Lucille begins to apply pressure, but as soon as the needle threatens to puncture the skin, the lump flees to the back of Jo’s neck, cowering beneath the edges of her hair. The suddenness of the movement makes them both jump.

“What the hell,” Lucille mutters, sounding both puzzled and faintly annoyed. “That’s no cyst.”

She reaches for Jo’s neck, but Jo steps out of her reach. It’s an instinctive movement, as though whatever engine powers the lump has compelled her to jump away from her wife’s questing fingers. Lucille raises an eyebrow and lowers her hand, still holding the needle.

“Don’t worry about it,” she says. “It’ll probably go away on its own. No one can see it back there, anyway.”

Lucille frowns, shrugs, nods. She leaves the needle at the edge of the sink, where it points due north to the faucet. At breakfast her eyes return time and time again to Jo’s neck, her expression thoughtful.

◊ ◊ ◊

As Jo walks to work, the lump slides around beneath her skin, investigating its newfound territory. It doesn’t hurt, although she feels it ought to. It doesn’t disgust her, although it ought to do that too. Its sly, careful movements only make her curious and calm.

By the time she sits down at her desk, the lump has wandered back to the front of her throat, apparently convinced the danger has passed. It sidles up along her jaw. She sees it reflected in the dark screen of her computer, bulging and obscene. It looks like she has the mumps. The lump twitches, as though aware of being observed.

She turns the computer on. Her reflection disappears in a flood of blue light and static.

There’s only one picture on Jo’s desk, a photograph of she and Lucille on their honeymoon. Hand in hand in front of Niagara Falls, flushed and smiling and wearing fanny packs that were meant to be ironic but turned out to be merely useful. Behind them, the Falls are a roiling white wall. The turbulent roar of water rings briefly in her ears, as though she’s standing there once again.

How long have they been married now? Three years? Five? Jo finds that she cannot recall. In many ways, it feels as though they have always been married, as though their union was a thing arranged years before they’d met each other in that crowded bar they used to go to, when they were both younger and thinner and less lined with worry and stress. It’s hard for her to remember now that moment when she’d looked up and seen Lucille for the first time, her direct, intense gaze focused on her from across the room, a hook sinking into her and tugging her close.

Or—had it been a bar? Jo frowns, reaching up to depress one finger into the soft surface of the lump. It might’ve been a party, now that she thinks of it, or a wedding. Or maybe she’d known Lucille’s roommate from when she was in medical school. The more she thinks of it, the exact circumstances of their meeting, the more muddled her mind becomes: she can see multiple possibilities unfolding in her wake, a dozen strands of history that drew them forward to where they are now and turned them into wives.

She sits at her desk and does her job. The lump makes its way from her jaw down to her collarbone, where it rests in the little hollow between her clavicles. It moves deliberately, like a snail. She likes the strange, slow slide of it, the feel of it travelling beneath her skin.

◊ ◊ ◊

On Jo’s lunch break, Lucille calls her just as she is about to bite into her sandwich.

“Has it gotten bigger?” she asks. She doesn’t identify herself, confident that Jo will recognize her voice.

Jo touches the lump. It does seem to be larger now, more of an egg than a marble. “I think so,” she says. “Harder, too. Feels like wet sand in a balloon.”

Lucille sighs. Her breath wafts through the receiver and tickles Jo’s ear. “I should’ve lanced it. Do you want me to come to work? I can bring tools from the hospital. A scalpel, or some tissue forceps.”

The thought of facing such an array of instruments, their wicked points and gleaming edges, makes her flinch. The lump seems to flinch as well, a pulsating throb she feels against her collarbone. “It doesn’t hurt,” she replies. “I should be fine.”

Lucille hums in dissent. For a moment Jo thinks that her voice sounds different, that it’s not her voice at all, that she’s speaking not to her wife but to a stranger. She shakes her head, the thought dissolving like sugar on the tongue.

“You know,” she says, “my grandmother in Newfoundland used to believe in fairies.”

Jo waits. Occasionally Lucille will speak in such non-sequiturs, give voice to thoughts that seem to have no connection to the world around her. The connection is always there; it simply has to be teased out, revealed.

“She said that sometimes, men who walked home through a dark field would be hit with something called ‘the blast,’” Lucille continues. “What other people used to call ‘elf-shot.’ They’d feel something hurt and come home with lumps on their legs, their arms. And when the lumps were open, they’d be full of things. Bracken, bones, bits of twig. Probably their way of explaining tumours, or something.”

“Well, I haven’t walked through any dark fields,” Jo replies. She is faintly amused by this superstitious digression from Lucille, who is always the steady one, the one with the brain that works in straightforward and sensible lines. “So I don’t think we can blame fairies for this one.”

There is a moment of quiet on the other end of the phone. Through the static, Jo thinks she can hear a sound, a keening wail, like the sound a rabbit makes when it’s frightened or dying.

“Come right home after work,” Lucille says. “We’ve got to fix this. I don’t trust that thing.”

This is not a command—theirs isn’t that kind of marriage—but Jo finds herself gritting her teeth. She murmurs assent and, after a few more flaccid marital pleasantries, hangs up the phone with more force than necessary. A co-worker sitting a few desks away glances up curiously from his screen, searching for the source of the noise. Jo takes a deep breath and tells herself not to overreact. Lucille is a doctor. She knows when things need to be fixed.

Calmer, she looks down at her sandwich. The pale mash of egg salad is spilling out of its corners, filling the air with the gentle stink of sulphur. She imagines the eggs forming inside the sticky innards of a bird and swallows a sudden surge of vomit. The sandwich is unceremoniously dumped into the trash can in the break room, despite the insistent growling of her stomach. To assuage her hunger, Jo chews on the various items at her desk: mechanical pencils, paper clips, an eraser in the shape of a fish. The taste of plastic and rubber linger on her tongue for the rest of the day.

◊ ◊ ◊

Towards the end of the afternoon, the lump begins to slip down her torso to her navel. It nestles there, a bulbous jewel, visible through the thin white cotton of her blouse.

In direct violation of her wife’s request, Jo does not go straight home after work. She chooses instead to go on a meandering walk through town, telling herself that she is simply taking the scenic route. She wanders down streets she has never heard of and into alleys that go nowhere in particular. Her hands hover over her belly like anxious birds. She cannot see the lump through the wool of her coat, but she can tell by the feel of it that it has grown.

Time crawls. The sky overhead grows darker, shade by shade, and when the stars come out, she tries to pick out constellations with her finger. The only one she recognizes is Aquila, its bright arrow pointing towards clusters and combinations alien to her. She imagines herself as an astronomer in a strange new world and tries to see shapes in the sky, giving them names. The Double Helix, she thinks, tracing it with her finger. The Tower Crane. The Mannequin.

She and Lucille spent their honeymoon camping in Tasmania. On their first night there, Jo left their tent to look up at the night sky and found that it was a stranger to her, its constellations all wrong, all changed. Her reaction had been startling: a long upwards stare, and then a high, thin scream drawn out on a single breath, like yarn from wool. Lucille had laughed, and then she’d frowned, and then she’d begged her to stop, pulling her inside the tent and covering her mouth with a desperate hand; but Jo continued to scream until, finally, she tasted blood in her mouth from her meat-raw throat. That soothed her. She fell asleep, then, despite the discomfort of the no-longer-ironic fanny pack, buckled tightly around her waist.

But no—there is the picture on her desk, the photograph of she and her wife in front of the Falls. That was their honeymoon, wasn’t it? Is she remembering the event wrong, or the picture? Were they in front of the waterfall, or were they standing on a beach in Tasmania, their backs to a blue field of ocean?

She doesn’t know. She can’t remember. The same scream tries to wend its way up her throat and out of her mouth, and she tastes blood.

The lump moves again as she continues to walk, sliding down the curve of her left thigh and calf. The sensation is almost pleasurable. When she looks down she can see it making a bulge in her black tights, resting comfortably above the line of her boots. A Magic 8 Ball. An oracle. She wonders if, like the lump, she’s slipped from one place to another, from northern to southern hemisphere, where all the stars are different.

◊ ◊ ◊

Lucille is sitting on the front step when she gets home, hands placed on her knees. The house is dark, the front door gaping open behind her. Beyond that door is their home, shrouded in darkness. The life they’ve built together. Their mutual wifehood, a commitment made tangible through the purchase of this house, its matching living room set and elegant dining room table.

“Hello, wife,” she says. She stands but doesn’t leave the step.

“Hello, other wife,” Jo replies, and swallows the urge to apologize. She stands empty-handed on the front lawn, her feet carefully planted. The heaviness of the lump, now the size of a small bowling ball and nearly as hard, has made her gait unsteady. She tugs off her shoes and pantyhose, flinging them away into the grass.

Lucille’s gaze travels downwards from Jo’s throat and onto her ankle. “Look how much it’s grown,” she says. “I don’t know if the things I brought from work will even do the job.”

Sharp edges and pinching tweezers, the whine of a circular saw. The lump shivers.

“It’s not dangerous,” Jo says.

Lucille shakes her head and steps towards her. There is something in her expression that makes uneasy little flames lick along Jo’s skin. “You don’t know that.”

“Neither do you!” This was an unintentional shout. It echoes strangely, and somewhere in the distance a dog howls indignantly. Once again Jo takes a breath, reminds herself to stay calm. A doctor, she thinks. My wife is a doctor. How lucky I am. Wives. “We could just ignore it,” she continues, quieter now. “In a few days you wouldn’t even see it. It would just be part of me. Like an arm, or a mouth.”

Her wife takes another step closer. She is on the grass; only a few feet separate them. “Mouths bite,” she says. “We have knives in the kitchen, tools in the garage. We’ll try everything.”

She imagines the bit of a drill piercing the thin blanket of skin that swaddles the lump, scrambling its innards like an egg. Something rises in the back of her throat, bile or acid or that same scream that writhed in her throat under unfamiliar stars.

“Our honeymoon,” she croaks. “Did we go to Tasmania, or Niagara Falls?”

Her wife frowns “Neither,” she replies. “We went to Japan. Mount Fuji, the Golden Pavilion. That shrine where you rang a bell for the god.”

She can see it then, that hazy blue-white mountain stretched across the horizon like a sleeping giant. But in the same breath she smells the salt of the Tasmanian beach, hears again the thunder of falling water. All three places, fighting to occupy the same space in her mind. She tries to speak and finds she is having trouble breathing, her throat closing tight as a fist.

Lucille looks at her with something that’s not quite pity. She closes the space between them and kneels at Jo’s feet, a supplicant’s pose that belies her actual purpose. The lump twitches insistently, its surface rippling with distress.

“Trust me,” she whispers, to one or both of them, and then she lays both hands on the offending growth before they can escape.

The lump shudders violently. A noise comes from deep within it, the wail of a dying rabbit. Lucille does not seem to hear it. She flexes her hands once, a pianist preparing at the bench, then takes a firm hold of it and begins to pull, her nails digging painful grooves into Jo’s flesh.

The lump’s movements did not hurt, but this does. Jo feels it in her bones.

“Let go!” she cries, trying to free herself, but her wife doesn’t seem to hear this either.

For a moment the three of them grapple together in tableau: Lucille tugging, the lump screaming, Jo wobbling above them like a streetlight in a gale, her eyes spilling over.

Then, with a sound like meat ripping off a bone, the lump tears away from Jo’s leg. The keening sound abruptly stops. She feels a breaking inside of herself, like the shell of an egg collapsing under pressure.

Jo expects blood, gore, a gaping hole where the lump had been, but when she looks down, her ankle is smooth and whole. Her wife opens her hands. Something fleshy squirms there before dissolving, bit by bit, into a pile of debris. A fairy-blast, Jo thinks, confused, but the debris contains material unlike what her wife described before: broken matchsticks, baby teeth, dead flies, dust.

Lucille whispers something soft and sweet to her fistful of trash. When she looks up, Jo sees that her eyes are bright, her mouth open and panting. The look on her face might be love, she thinks. She hopes.

“I fixed it,” Lucille says, spreading her fingers wide. Bits of yarn and dryer lint tumble through them to the grass. “See? You’re better now.”

Jo says nothing. She’s thinking about ringing a bell outside of a shrine, of standing damp and exhilarated in the spray of a waterfall, of screaming into the gaping void of the stars.

The wind picks up, and she watches it take what’s in her wife’s hands, scattering it into the dark.

…

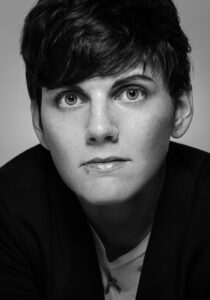

A 2020 graduate of the Simon Fraser University Writer’s Studio program, Elliott Gish’s work has appeared in The New Quarterly, Wigleaf, The Baltimore Review, Vastarien, and others. Her debut novel, Grey Dog, will be published by ECW Press in Spring 2024. She lives with her partner in Halifax, Nova Scotia.

A 2020 graduate of the Simon Fraser University Writer’s Studio program, Elliott Gish’s work has appeared in The New Quarterly, Wigleaf, The Baltimore Review, Vastarien, and others. Her debut novel, Grey Dog, will be published by ECW Press in Spring 2024. She lives with her partner in Halifax, Nova Scotia.