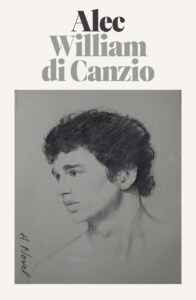

William di Canzio, Alec (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2021), 352 pp., $27.00 US.

I’m a sucker for gay love stories. They’re a sensuous, sugary hit of pure emotion. William di Canzio’s Alec is not without problems—like its source material, E. M. Forster’s posthumously published novel, Maurice—but it’s got that sweet centre I crave.

Set in England right before World War I, Forster’s original work is a thoughtfully rendered mess. It tells the story of the love affair of Maurice Hall and Clive Durham, who meet-cute at Cambridge during a time when homosexuality was an imprisonable offense in England. Though Oscar Wilde’s tragic demise nearly two decades earlier is never mentioned in Forster’s work, it looms ominously over its events. Fearing arrest and loss of social status, Clive forces a sexless purity onto his affair with Maurice, ultimately calling it off and entering into a marriage of convenience.

Forster’s intent, though, was to write a story with a happy ending. To do this, he rather improbably pulls young Alec Scudder out of his hat to be Maurice’s love interest and the catalyst for his sexual awakening in the back third of his novel

In di Canzio’s sequel to Forster’s tale, Alec Scudder is far from the loosely sketched cipher of the original. He’s a smart, inquisitive youth, who takes so well to his studies that he’s allowed to continue them beyond what was customary for the working class at that time.

In di Canzio’s telling, when Alec is finally booted from school, he lands as an under-gamekeeper—first at the estate of Lady Wentworth, then at that of Lady Durham, Clive’s mother. Alec resents being a servant, but is drawn to caring for the game stock and working outdoors. Continuing his interest in the life of the mind, di Canzio’s Alec attends classes at the nearby Workingman’s College. There is one thing, though, in which he has absolutely no interest: girls.

Here the sequel becomes a bit of a slog as di Canzio retreads the events of the original, as he must if he’s to appeal to those who haven’t read Forster’s novel or who haven’t seen the excellent 1987 Merchant-Ivory film adaptation.

Chafing at his fate of a lifetime in service, Alec agrees to join his brother’s business venture in Argentina. Meanwhile, Maurice plods through his meaningless existence as a stockbroker, resigned to a life without love.

In di Canzio’s novel, the somewhat muddied action toward the end of Forster’s tale is clarified by being told from Alec’s point of view. Now when he claps eyes on Maurice, it isn’t the equivocal act it is in the original—it’s love and lust at first sight:

Alec locked eyes with the man, a handsome fellow with black hair and a mustache. He felt a sudden charge. Just as suddenly—and to his surprise—he understood it was mutual. The guest’s expression softened, unwillingly, it seemed, from anger to mildness. What was Alec seeing? Desire, loneliness, longing, even helplessness? The man’s lips parted, as if to speak, but he did not.

Building on this moment, di Canzio provides the motivation the source material lacked for the novel’s pivotal brash act: Alec sneaking one night through the window at the Durham Estate to fall in bed into Maurice’s waiting arms.

Having dispensed with the events in Forster’s Maurice, di Canzio’s sequel takes off. The young lovers overthrow their previous lives and join London’s demimonde and the Bloomsbury set. There, they meet the flamboyant Lord Risley from Forster’s novel. Alec is reacquainted with the imperious Lady Wentworth, his former employer and future benefactress. In this new life, Alec and Maurice attend the symphony, go to parties, to underground gay clubs. Alec is an easy fit with an upper crust set whose outlier status liberalizes their views regarding class.

Forster modeled the Alec/Maurice relationship on that of his acquaintances, the gay rights advocate Edward Carpenter and his working-class lover, whose partnership lasted almost forty years. Di Canzio pays homage to this couple in the characters Ted and George, who become some of Maurice and Alec’s many allies.

In the third quarter of the book, their love affair is eclipsed by World War I. This two-year separation, imposed by the setting of the original work, caused Forster to abandon his own epilog to his novel, though he tinkered with the manuscript for years.

Di Canzio, though, throws himself into the task—describing Maurice’s experiences during the disastrous Gallipoli campaign, and Alec’s stints in the trenches, his times when on leave, his long convalescence from shell shock in the south of France.

In this section, the prose—which trends to the purple during the romantic interludes—becomes muscular, viscerally describing the atrocities and inanities of the long war. As here:

The mules died, many at once. It was as if on reaching the line, their destination, the animals chose death rather than be forced to go farther. They dropped where they stood. When the men were unpacking their carcasses, some wept to see how the straps of their burdens had flayed the beasts’ hides. The best they could do for them was to shove them to the side of the road.

After his hasty evacuation at Gallipoli, Maurice entirely vanishes from the novel. It is just this narrative gambit that Forster must have feared, as it removes the engine driving the story—the relationship between the two men. Without it, the novel lags somewhat, until they are at last reunited.

In the concluding pages, the lovers work out the shape of their future life together. When Maurice’s younger sister has a child of color out of wedlock—perhaps a more serious offense in the day than homosexuality—the principled Maurice and the equally loyal Alec find themselves joined in a new kind of family.

All this is relayed in prose that pays homage to Forster’s style that, while penetrating, can now seem overly florid. Take this example when Forster writes of Maurice’s turmoil over his sexuality:

…on he struggled with his back to ease, because dignity demanded it. There was no one to watch him, nor did he watch himself, but struggles like his are the supreme achievements of humanity, and surpass any legends about Heaven.

Di Canzio responds in some sections as though writing a bodice-ripper. As he does here:

Overwhelmed by the twin riptides of youth and ardor, the lovers ravished each other, panting and gasping like drowning men…. Thus the outlaws abandoned themselves yet again to their unspeakable crimes. And the night smiled…

It’s hard for a modern reader to keep a straight face while reading this—I mean, we’re talking about two men fucking their brains out here! While I applaud di Canzio’s decision to unify the two books stylistically, I believe he would have been better served by the robust style he employs in the war sections when it comes to these gushy bits.

Still, di Canzio’s portrait of the trials and felicities of these two men beautifully succeeds in fulfilling Forster’s intent. For, by the end of Alec, love prevails. No spoiler here. In the spirit of the original, this ship is built to sail off into a happy ending.

…

Lucian Childs is a Canadian-American writer living in Toronto, Ontario. His debut work, Dreaming Home, is forthcoming from Biblioasis. He is a co-editor of Lambda Literary finalist, Building Fires in the Snow: A Collection of Alaska LGBTQ Short Fiction and Poetry. His stories have appeared or are forthcoming in literary journals Grain, The Puritan, and Prairie Fire, among others. Find more at Twitter @lucianchilds and on the web at lucianchilds.com.

Lucian Childs is a Canadian-American writer living in Toronto, Ontario. His debut work, Dreaming Home, is forthcoming from Biblioasis. He is a co-editor of Lambda Literary finalist, Building Fires in the Snow: A Collection of Alaska LGBTQ Short Fiction and Poetry. His stories have appeared or are forthcoming in literary journals Grain, The Puritan, and Prairie Fire, among others. Find more at Twitter @lucianchilds and on the web at lucianchilds.com.