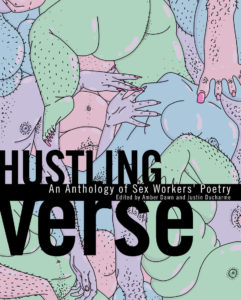

Amber Dawn & Justin Ducharme, ed., Hustling Verse: An Anthology of Sex Workers’ Poetry (Arsenal Pulp Press, 2019), 192 pp., $19.95.

The poetry collection Hustling Verse, edited by Amber Dawn and Justin Ducharme, is a book I want to judge by its cover. The artwork is stunning. From afar, it seems as if it’s a molted collection of pastel pinks, blues, and greens; a scattering of sea shells or birthday candles; something abstract. It’s only on closer examination that the colours take on the form of bodies. Big bodies, small bodies. Bodies with hair, bodies with scars, tattoos, and other markings. There is no solid person on the cover, only a mixture of people, all of them touching. Their intimate touches are meant to signify that this is a collection of sex worker poetry written by sex workers. I’ve wanted to read this since I read the call for submissions on the Lambda Literary page, because this fact alone—sex workers writing about their lives poetically—is a rare artistic creation. But I want to hold the book close, and judge its cover in the best way possible, because I can’t get one thought out of my head: Everyone is touching.

This is fundamentally a book about touch. Of course, it is about sex work and the acts of intimacy or physicality built around sex work—but it is also about touch in so many other ways. The good touch from a friend’s hug, or the bad touch from a family member. The loss of touch from a sense of self which cannot exist in certain conditions; the desperation to stay in touch with friends and family; and the touched feeling that sometimes exists between strangers in moments of triumph and exaltation. This is a book about touch that I have always wanted to read, though I must preface this review by stating that I am not a sex worker. This fact, as Dawn writes in her preface, means I’m an “outsider” in this world. Reading that word—outsider—in a preface was another kind of touch the work exudes: a defensive measure, a signal to slow, to stay back. It is a word that I know hit me harder than it meant because I am touch starved right now.

When I read this work, it was my eighth week of lockdown from COVID-19. Hustling Verse now feels like a scarce resource in a world where we are supposed to stand six feet apart from one another and only go to the grocery store. The public sphere is nearly completely shut down, which means that the private world now takes precedence, and hidden economies inside these private spaces—like sex work—seem to come out into the light.

And yet, we still can’t touch. It is illegal to gather with people, like some sex work still is illegal. So of course, when I saw the cover of the book, all I could think about were the bodies. The space—or lack thereof—between them. It felt so beautiful and transgressive, more now than ever before.

At its core, Hustling Verse is about touch, but it is also a collection that is filled with rich details—not all of them pretty—which are then used to flesh out and make humane a world that most average readers might not come across (or only come across through their own misguided perceptions). This book is supposed to be a discovery, and it is meant to be beautiful in my hand as I read, but the fact that it is also a discovery means that it has been hidden for so long.

As Amber Dawn points out in her introduction, before this collection, she seemed to be the only published and recognized poet who was also a sex worker. Her memoir, How Poetry Saved My Life, is a testament to her narrative of poetry and survival, which is also another core concept of this collection. As Dawn and many other poets note, sex work is often something done for the sake of survival, be it monetary or psychological. Because of that, it can be ugly and brutal, such as Lester Mayers depicts in the stunning poem “Cynicism” which begins with the morning sun gazing “upon his bruised, / bloody black body kicking awake his reality.”

Hustling Verse also depicts sex work as magical, stunning, and visionary—but it might not be the same type of visionary beauty that an average reader might suspect at first glance. It is the tension between the imagined, and the visceral lived reality of, the sex worker which gives this collection its power. In some poems, we see the gritty reality of violence, be it interpersonal through a bad interaction, or we see it in the grander narrative of systemic violence, institutional racism, colonialism, and so on. These realities are not shied away from, nor are they twisted into a made for TV movie where the sex worker prospers at the end by getting out of the life. That narrative—where sex work is seen as unilaterally bad—is too easy; it is the pop culture one. It is one that lacks the depth and nuance of real life experience, which Dawn, Ducharme, and their poets have in so many words.

Dawn has written that novel, anyway. In her 2010 novel Sub Rosa, she writes about the main character’s (nicknamed Little) search for her way out of sex work and her true name. On the surface, it can seem like this narrative is the heart of gold stereotype—but that’s the thing. Dawn delights in surfaces; Little’s time in sex work is an act of survival, but it is also a beautiful, wild place where she meets a bunch of women and men who are just like her. They are part of the mythical underground world where sex work happens, called Sub Rosa, and run by a half dozen people who seem just as magical as the people who inhabit and work there. This is what Dawn is good at: taking real life, especially the real life of those who are marginalized, and then recasting it with neon colours and bright auras. With nail polish and familiars and spellwork inside a massage parlour, as she does with her final poem called “The World’s Oldest Love Spell (a Fairy Tale).”

Dawn is not the only one whose work is imbued with magic and mythology. Irene Wilder’s poem, “Ode to a hooker, without the usual vocabulary” depicts a long line of women as they grow tired of waiting and instead become “the sickle-edged moon” and “mean-mouthed” or a “mama wolf.” Similarly, in Tzaz’s “this is not mythology” the speakers recounts mermaids and goddesses, indulging in the cultural milieu of the mythic woman, while also demanding “a $300 stride to dock” in order to be fairly compensated for her ability to become that perfect dream for someone else. The stereotypes of women, young girls, and sex workers collide in this collection, and it is when the mythology is indulged in—but also pulled back tightly within the same poetic breath—that I found most exhilarating.

I love these poems the most because they are taking that potent myth of the sex worker that our cultural imagination relies upon and leaning into it. But instead of merely rehashing bad narratives, ones which ignore the larger systemic violence at their core, they insert magic in the corners. Trauma, then, is not meant to be something that takes someone down and keeps them down forever; trauma is merely the first step in the grander narrative of survival, where the person at the centre is firmly in charge of their voice and actions. With some added magic, these poets are then able to elevate themselves beyond forced myths and into something better. For the readers, we get a glimpse of that hopeful future, and it is one fundamentally anchored around this idea of touch.

When this review will be published, I hope some of the COVID-19 restrictions will be lifted—but I know that the world will be changed. There is massive potential in this change; for magic, for mayhem, and for a systematic subversion of power like these poets cry out for. I am still an “outsider” here in their world, but I know that the voices in Hustling Verse now seem more prophetic and revolutionary than even before. We need touch. We need to touch others and keep being touched. It is the only way we will survive.

Eve Morton is a writer living in Ontario, Canada. She teaches university and college classes on media studies, academic writing, and genre literature, among other topics. Her collection of poetry called Karma Machine will be released in 2020. Find more info on authormorton.wordpress.com.

Eve Morton is a writer living in Ontario, Canada. She teaches university and college classes on media studies, academic writing, and genre literature, among other topics. Her collection of poetry called Karma Machine will be released in 2020. Find more info on authormorton.wordpress.com.