Brett Josef Grubisic

A few years ago I got a mid-afternoon call from a friend. Originally he and I weren’t friends, not exactly; as strangers we’d made contact surreptitiously online and met for quickies on sporadic afternoons, work routines permitting. After a while the camaraderie flourished as the erotic heat petered out and we began friendly post-fling socializing—catching up on news over coffee, say, or running errands. No surprise, the conversations of this evolving relationship often touched on sexual adventures that were either out of the ordinary or comically disastrous.

That afternoon, however, my friend wasn’t calling about my schedule. He told me that an uncle, the “confirmed bachelor” of his extended family, had died. Sorting through possessions in the uncle’s apartment, he’d found cardboard boxes in a closet. Had their contents been discovered by somebody else, perhaps someone supposedly concerned with preserving family dignity or maintaining the man’s reputation as a choosy bachelor who’d “never found Miss Right,” the boxes would have been tossed out without a second thought. Instead, his nephew wanted to make use of them.

If you’re now picturing a heaped dildo collection or feather boas tangled with size 14 heels, you’re getting warm. Mostly, the boxes contained old porn magazines. Reams of them, all gay: Blueboy, Honcho, Inches.

My friend wanted another opinion about the stash. I cycled over to his house in a matter of minutes. After all, who’d turn down a chance to riffle through a trove of vintage porn. That bygone pictorial style—epic moustaches above, black leather vests in the middle, tight jean cut-offs below! Those exotic ads for Spanish fly and amyl nitrite, both of which, incidentally, are banned in Canada!

I helped my friend sort through the bulk of the material. We divided the exclusively American mags into 1970s (sell) and 1980s (recycle: locating a used bookstore willing to purchase them struck us as a lot of driving and little reward). The uncle had kept nothing newer than issues from about 1982; we guessed that he’d had peculiar taste in models or had lost interest in the magazine format altogether. A secret till the end, his off-the-record existence and its details would remain exactly that.

My friend hoped that the really old magazines might be valuable; ultimately, though, he arranged for a historical archive in Toronto to take possession of the lot.

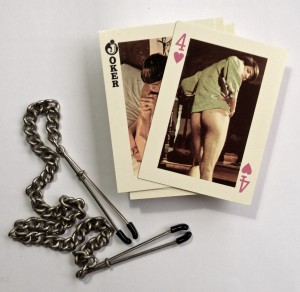

From the piles I grabbed a few items that, years later, still sit in my apartment. A deck of novelty playing cards, circa 1969. Naked shaggy-haired male models bend, squat, or sprawl on each card, jokers included. There’s a pair of nipple clamps as well. Tarnished steel and on a heavy chain, they’re of unknown vintage.

From the piles I grabbed a few items that, years later, still sit in my apartment. A deck of novelty playing cards, circa 1969. Naked shaggy-haired male models bend, squat, or sprawl on each card, jokers included. There’s a pair of nipple clamps as well. Tarnished steel and on a heavy chain, they’re of unknown vintage.

I’ve never used the clamps. As for inviting friends over for an evening of strip poker with those soft-core cards, well, no. Some ideas are best left untested. The clamps reside in a sock drawer, the cards on a bookshelf. Whenever I catch sight of them, though, they never fail to intrigue me. Just mass-produced consumer goods, they’re potent nonetheless, physical reminders of ancestry. Roots.

Any time I’m in the mood, I can flip through my Aunt Ruth’s labour of love, a hand-drawn and photograph-laden history of several generations of our family. With a finger I’ll trace staggered lines to England, Scotland, and what was once Austria-Hungary. And—after what must have been unpleasant, steerage-class Atlantic voyages—to Nova Scotia, the Canadian prairies, and the American breadbasket. (Moundville, Missouri, one of my father’s ancestors’ previous haunts, isn’t on my bucket list, but I’d stop by if in the vicinity.)

Usually, lineage is thought to provide a useful, even necessary foundation and clarifying explanations. Here’s where you come from, you learn: right there’s the village your grandmother’s grandmother once called home; on him you can spot the source of the distinctive family nose; this region explains your cheapness, temper, affinity for boiled potatoes or frowning.

Gay ancestry’s different. Like striving to make non-family connections to others in the distant past who were left-handed or Canadian (in my case), there’s quite a lot of creative fabrication involved with envisioning a gay family tree and the commonalities that might persist along gay roots. Queers over the millennia might share a genetic marker, true. There could be a strain of kindred sensibility or way of viewing (or being part of) the world, even a profound sense of being regarded as a generally unloved and square peg identity in a round hole world.

Then again, that commonality might be wishful thinking, or a delusion with good intentions.

Even so, I’m drawn to the idea of a family resemblance between queers across the eras. It’s grounding of a kind, an anchor. If I could be magically teleported to 1969 and play a few rounds of poker with the man who owned that deck of naked man cards, would the setting, the conversation, and the mannerisms strike me as familiar enough to also count as familial? If I travelled back still further, to the former card player’s childhood, and met “my kind”—criminals all, technically speaking—what then? Would the experience be one of recognition, as when I stare at a Depression-era photograph of the creased and unsmiling faces of those dour Eastern European relatives on my father’s side and somehow know them? I expect so.

In part, that’s why I believe the impulse to keep those boxed artifacts was pretty much automatic, a reflex. Or, alternatively, that pitching them out struck my friend and me as foolish, a wrongheaded act of eradication of self and community and lineage.

Right now that bric-a-brac—yes, even the cheesy novelty card deck—links me directly to a fundamental section of my root system and communicates something integral about those men and women who came before me.

The material fact of those objects, the weight of them in my hand, might mean nothing, I realize, but that they exist at all gives me a pleasant feeling of historical continuance.

That’s important to possess, I think. Even now, almost fifty years past the “Gay is good” activism that took off in the late 1960s, we’re not a culture or community or tribe (the tag depends on point of view) with much in the way of historical documentation. Schools don’t offer field trips to permanent museum exhibits titled Queer Lives: From Sappho to Tim Cook. My guess is that a unit called “Mainstream Attitudes to Sexual Minorities since Ancient Greece” hasn’t quite made it into high school curricula. I’d bet too that that when most parents instruct kids about sex, they don’t bother to set aside an extra session—just in case—that describes in any way historical understandings of sexual minorities.

Our roots, in short, are sparse and prone to disappearing. Typically, as I understand it, queers to this day grow up in a historical void. There might be an awareness of a lesbian character here, a gay politician there, and the latest singer, actor, or sports star who has come out. Before the here and now, though, there’s not much. Regrettably, the net effect is an unrooted populace.

All of that is understandable. Sexual minorities of all kinds still grow up in and face a world that hates, persecutes, oppresses, politely accepts, legally tolerates, or slyly erases them. And our collective history—with its let’s not talk about its and dare not speak its names … and arrest records, obscenity trials, persecutions, secrets, exilings, suicides, double lives, marriages of convenience, and lurking in the shadows—is hardly a Hallmark message. On top of that, physical evidence just doesn’t persist. Boxes from confirmed bachelor uncles get thrown away, the material evidence of such lives kept buried and unknown.

To me, though, keeping and sharing artifacts counteracts invisibility, forgetfulness, and erasure. Doing so adds real, touchable objects and tells a themed story—persistence despite the odds, say, and the courageous will to be. A ridiculous expectation from an old deck of cards? Maybe, but how else can we know about our extensive queer lineage without such possessions?

◊ ◊ ◊

Aside from the nipple clamps and playing cards in those boxes, I brought home a few booklets that were part of the uncle’s literally closeted unofficial library. These curiosities were evidently a product of their historical moment.

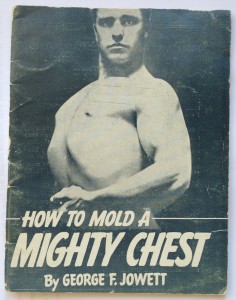

How to Mold a Mighty Chest, a 1938 booklet from the Jowett Institute of Physical Culture of New York City, for example, explains how to build a “impregnable, dynamic, vitallic [sic]” set of pecs.

How to Mold a Mighty Chest, a 1938 booklet from the Jowett Institute of Physical Culture of New York City, for example, explains how to build a “impregnable, dynamic, vitallic [sic]” set of pecs.

Illustrated with hardcore scenes in porn-set toilets, Headhunters, with a foreword by “Jerome Rose M.D.,” claims to be educational, a “complete study of sexual practices in public restrooms by the male homosexual.” After taking a stab at formal language—“I shall give some case examples,” etc.—the author’s descriptions turn into standard issue erotica (“Jack grabbed Don’s pulsating, ivory rod …”) until the end. Throughout, this “case study” of sexual practices devotes a few pages to advertising other fake-scientific mail-order titles from New York, Homosexual Sexuality and Photo-Illustrated Male Homosexual Marriages. The eternal mysteries of either of those were available to those twenty-one or older for $5.95 (which is $37 in today’s dollars).

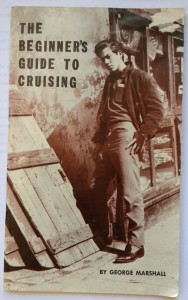

Another oddity is George Marshall’s The Beginner’s Guide to Cruising (published in 1964 and once available for $3 from PO Box 7410 in Washington DC). It’s surprising insofar as what it’s not about: cruising in the contemporary sense. No, it’s about the art of hustling. The cruiser here is a guy who navigates the tricky world of flamboyant gays. “Natural aesthetes,” the authors declares of the cruiser’s prey, “resent the vulgar, the gross, the gaudy, the harsh, the crude, the cacophonic.” “Emotional rather than rational,” gays are useful to the cruiser for money, food, drinks, sex, shelter, and whatever else is desired. To everything there is a season, of course, and these cruisers eventually moved on (“Leaving gays is just as much an art as conquering them”) and targeted new aesthetes for conquest. Apparently, any cruiser that settled down was a poseur, a gay in cruiser drag. If you wanted to be a cruiser in the early 1960s, this guide covered every element required for success.

Another oddity is George Marshall’s The Beginner’s Guide to Cruising (published in 1964 and once available for $3 from PO Box 7410 in Washington DC). It’s surprising insofar as what it’s not about: cruising in the contemporary sense. No, it’s about the art of hustling. The cruiser here is a guy who navigates the tricky world of flamboyant gays. “Natural aesthetes,” the authors declares of the cruiser’s prey, “resent the vulgar, the gross, the gaudy, the harsh, the crude, the cacophonic.” “Emotional rather than rational,” gays are useful to the cruiser for money, food, drinks, sex, shelter, and whatever else is desired. To everything there is a season, of course, and these cruisers eventually moved on (“Leaving gays is just as much an art as conquering them”) and targeted new aesthetes for conquest. Apparently, any cruiser that settled down was a poseur, a gay in cruiser drag. If you wanted to be a cruiser in the early 1960s, this guide covered every element required for success.

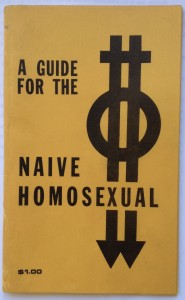

Of the lot, my favourite is local and handmade; costing a dollar, it’s a zine from before that term was coined.

If you’ve ever tried to picture queer life in Halifax, Red Deer, or Prince George in the late 1960s or before and can produce nothing whatsoever (or only come up with one of those sad episodes of getting caught, arrested, or rejected, or drowning sorrows in booze, as Mad Men highlighted so well), then this booklet is fascinating for its ability to fill in some of the blanks.

Roedy Green’s A Guide for the Naive Homosexual (my copy is the eleventh revision, dating from March 1971) is an all-purpose instruction manual. Typed, photocopied, hand-stapled, and proudly featuring “BETTER BLATANT THAN LATENT” on its fiftieth and final page, Guide is a spirited, funny, sarcastic, and educational collection of information.

Roedy Green’s A Guide for the Naive Homosexual (my copy is the eleventh revision, dating from March 1971) is an all-purpose instruction manual. Typed, photocopied, hand-stapled, and proudly featuring “BETTER BLATANT THAN LATENT” on its fiftieth and final page, Guide is a spirited, funny, sarcastic, and educational collection of information.

Green printed a Vancouver PO box and telephone number of the back cover of his “complete guide for Canadians of either sex who feel they are homosexual, but who know nothing about how to meet other homosexual people.” Inside, the author describes his project’s origin in 1969. He’d once been a “reasonably miserable un-come-out gay” who’d searched for years but failed to meet any like-minded men. Finally, a friend took him to a gay club. “Ever since that day,” Green writes, “I have been one of the happiest people alive.” Wanting the same for Canadian readers near and far, he offers all kinds of advice about its attainment.

Aside from a queer lingo glossary (“Bull dyke,” “KY,” “Mary,” “Trick”), the latter part of the booklet includes a reading list (of non-fiction studies and American homophile publications; none are Canadian) and a twelve-page appendix with descriptions of every gay and lesbian place in Canada the author had visited or been told about, including baths, toilets, bars, and parks. He gives addresses and adds warnings about stabbings, violence, police, hustlers, and local etiquette.

Candid, unapologetic, and often catty, Green’s emphasis is sex first, socializing after the fact.

Here’s Green reviewing the New Moon Cafe in Lethbridge: “Pick-ups if you are not choosy.”

A steam bath in London: “Gay, hypersensitive, paranoid, but good.”

The Strand Theatre in Edmonton: “A lively back row, but is definitely not recommended except for the most brazen and desperate people.”

Meanwhile, the Vanport “is the main lesbian hangout in Vancouver. It is not recommended as the crowd is quite rough with a lot of pot users and heroin addicts.”

As a snapshot of queer Canada some forty-five years ago, Roedy’s appendix offers a rougher alternative to the Stonewall origin story that’s come to serve as a global, iconic political moment, the event from which modern GLBTQ consciousness is thought to have sprung. Instead of the adamant “No!” to the police and oppressive dominant culture and the ideology of “We’re here, we’re queer, get used to it” that followed soon after, the images provided by A Guide for the Naive Homosexual show a quieter, grittier struggle. From Victoria’s Beacon Hill Park and Quebec City’s Cafe Chez Paul to Edmonton’s Dreamland Theatre (“a real hole of a place to be used only by those unafraid of V.D.”), Green conveys the risks but also the irresistible force of desire that men had to meet other men for sex, companionship, and conversation. (The Guide admits to a limited knowledge of lesbian hangouts and cruising grounds, but Green’s accounts of the Vanport, the Pompernik in Quebec City and the Club in London suggest a similar pattern.)

As a portrait, it’s shadowy and discomfiting for certain. With the hustler economy, toilet stalls, syphilis vectors, and “anything goes” philosophy, the scenes are probably way sleazier than proponents of “Gay is good” would hope for. As a documentary picture of the history of my people, though, I prefer to focus on the fact that these men and women felt compelled to risk arrest, humiliation, career loss, violence, and public shaming in order to meet—talk to, argue with, kiss, fuck—others. Acted on, their desires and needs invented community of a kind—fleeting, secretive, in darkness—within a larger world whose routine messages reminded them they were a sickness, sin, and a criminal perversion that shouldn’t ever speak out, find love, or exist at all.

Before the addresses of hot spots across Canada, Green gives ample advice on assorted topics—friendship, coming out, sex, cohabiting, and the commonplace societal views about homosexuality (which he simply dismisses as close-minded prejudice). Though he was writing at a time when secrets, shame, and constant wariness were everyday habits, his unapologetic outlook and the advice that comes from it points to a future that’s so utterly familiar in the twenty-first century that it’s barely noticed and merely taken for granted. But with his DIY mail-order project, Roedy Green was a one-man Stonewall. He understood the world and the place of his kind in it and refused to accept the dismissive judgments. He wanted his alienated brothers and sisters, all of them, to meet. To have sex or a drink or, who knows, swap stories of work, sports, or family. He’d found happiness and thought that since others deserved it too, he’d help make that happen.

It’s a touching story, right? Without my friend and his uncle’s boxed collection, I could never tell it. We’re lesser as individuals and a community when such moments are hidden, lost, or forgotten. When poring over Roedy’s Guide and catching sight of those novelty cards on the bookshelf, I’m gladdened by their very existence. In sharing those artifacts and my thoughts about them, the value of Green—an ancestral stranger—and his project returns to mind: to share stories, to disseminate information, to build or maintain community, to secure happiness. Brave and necessary circa 1970, his beliefs remain crucial forty-five years later.

A UBC prof, Brett Josef Grubisic has written fiction including the novels The Age of Cities and This Location of Unknown Possibilities. His current novel project is set in a small BC mill town in late 1980; From Up River, and One Night Only tells the up-and-down tale of two sets of teenage siblings who form a New Wave cover band.

A UBC prof, Brett Josef Grubisic has written fiction including the novels The Age of Cities and This Location of Unknown Possibilities. His current novel project is set in a small BC mill town in late 1980; From Up River, and One Night Only tells the up-and-down tale of two sets of teenage siblings who form a New Wave cover band.