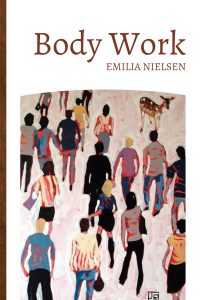

Emilia Nielsen, Body Work (Signature Editions, 2018), 100 pp., $17.95.

My skin tells non-linear tales: a series of abandoned forays into shrinkage and growth; into sun exposure and cooking burns (reader, do not cook fatty proteins sans shirt); into stretched pores and the friction of constraining clothes. The dark peach of Ashkenazi / Scottish skins such as mine are, in my here and now, white—privileged racial hue imbued so often with might and right. Read the strange vertical wrinkle between my eyes as a memory of the tendency towards the thoughtful furrow. Read the laugh lines as evidence that the furrow erupts quickly into fey giggles. Perhaps a pansy-purple butt-bruise refuses to forget a fun night, blooms more in the mirror each day. Skin raises eyebrows—every bit as much as my stretch marks mark me, to many, as a certain type of (selfish) self.

I offer, above, a humble example of what Emilia Nielsen, in her sophomore effort Body Work, might call “Dermographia.” The word—coined to convey Nielsen’s insistence that skin functions as a text—combines the Greek root derma (skin) and the Latin suffix graphia (having relation to writing). According to Nielsen’s opening lines, however, my dermographic method may fall short:

More than some accounting of notches, scrapes?

This birthmark, that mole. More than description

(decorative script).

To stray, surface. Dig a little.

Become floozy, flimsy: dermographer? (11)

So Nielsen, Assistant Professor at York University, wants us to do more than catalogue our skin’s markings. In my reading, she wants readers to write about and on our skins in new ways that change us. Consider this excerpt:

autopoiesis: self-producing, -creating;

living system: more (or less) than machine. Becoming

dialectic: fire and lifeline, ice and leaf. Becoming protein,

organelle, membrane. Becoming mollusk,

cellular. (89)

Though I want to set the book up on dates with works by Franz Kafka (he whose “In the Penal Colony” carves one’s crimes directly upon the body as a form of slow execution) or Jeanette Winterson (she whose Written on the Body remains a coming/cumming of age text for many queer desires), this repetition demands that Deleuze and Guattari (philosophers whose theories of “becoming” span many a book) are invited along too. Readers don’t need to have tackled any of these texts to let Body Work under their skin; even in the excerpt above, Nielsen uses words like “autopoiesis” but immediately defines them, as if letting each line peel itself back into the next. I appreciate this combination of challenge and invitation.

It hearkens to the book’s most vociferous precursor: écriture feminine, “the inscription of the feminine body and female difference in language and text” (Showalter, “Feminist Criticism in the Wilderness,” 249—and take this dated collusion of femininity and ‘female’-ness with a rock of salt). This strand of women’s writing, dating to the 1970s, uses repetition, word play, excess, and cyclical form—all of which are Nielsen’s tools too. To show what I mean, here is an excerpt from key figure Luce Irigaray:

And the sea can shed shimmering scales indefinitely…And each one is the equal of the other as it catches a reflection and lets it go. As it preserves and blurs. As it captures the glinting play of light. As it sustains mirages. Multiple and still far too numerous for the pleasures of the eye, which is lost in that host of sparkling surfaces. And with no end in sight. (Marine Lover, 46)

Aside from the shared interest in surfaces/skin, the rhythm and emphasis created by Irigaray’s anaphora—the repetition of “And” or “As it” at the beginning of almost every short sentence—also gives cadence to Nielsen’s work. These two short poems illustrate this vividly:

Onycholysis Photophobia

Of finger, nail loosen- Dissimilar to fear, irrational belief,

ing from root. Of not the pang of public places just can’t.

rootless, itinerant. Of Can’t daylight or fluorescent. Can’t sun.

rove, ramble, travel Can’t light-filled, luminous. Can’t gleam.

from nailbed. Of Can’t glimmer. Can’t flash. Can’t flume.

peripatetic, nomadic Can’t bear to. Can’t look away. (27)

Of drift and slipping. (26)

Sometimes Nielsen takes alliteration even further than her precursors do: “fracture friction fiction refraction / resistance resilient refuel / rapture rupture wrap-it-up” (15). Irigaray anticipates: “Fiction engenders fiction. Projections, reflections, fantasies” (Speculum of the Other Woman, 251).

I bother to underline Nielsen’s influences because I want readers to have a sense that this book joins a particular conversation, and it may be useful to know that the particular conversation of écriture feminine is one that eschews easily defined voices or characters or personae.

To be clear, I think that is Nielsen’s intellectual goal: to tell readers that both skin and text are never a unity, never a complete picture, “Never the whole “ (16). In a culture that demands one to present a unified and totally coherent self, this call for incompletion is worthy. Again, Irigaray foresees this: “[we are] a strange kind of two, which isn’t one, especially not one. Let them have oneness, with its prerogatives, its domination, its solipsism: like the sun” (Speculum, 207). Irigaray’s contention that oneness/unity in language is “solipsis[tic]” (or self-obsessed) pops up again a few pages later in Nielsen’s work: “*(dermograffiti): skin littered, lettered, / lexical. Tagged: solipsistic. Sloppy / pas de deux: medium and meaning” (20). Both Irigaray and Nielsen advocate for imprecision of voice, and both do so by contending with the threat of solipsism (to focus only on the self or oneself).

And it would be understandable if some readers’ tastes inclined them to wish for more personae, or story, or catharsis, or explicitly political or otherwise outward-looking or outward-feeling content in this book. Body Work isn’t easy or entertaining in a mainstream way. I suspect that it aims instead to motivate readers to learn to live with the difficult dance (“Sloppy / pas de deux”) that is textuality’s inevitable slippages of “medium and meaning” (20). Can we ever “say” what we “mean” with our bodies? How do you live with the reality that a skin—say, your skin—is not impermeable, fully knowable, unified, or otherwise “not one” (Irigaray, Speculum, 207)? The book is playful, but it’s called Body Work for a reason: it can be laborious indeed to face the incapacity to be completely sealed-off bodies and selves. The extent to which a reader considers this an important goal may determine the extent to which they enjoy the book (and certainly, enjoyment is but one possible positive outcome).

All in all: in a culture obsessed with making dark skin lighter, old skin younger, loose skin tighter, scarred skin less visible, and hairier skin more smooth, here is a book that takes “derma” out of the cosmetics industry (dermabrasion; asshole bleaching) and the health sciences (dermatology; dermoplasty) and puts it in the hands of writers and readers. This is not to suggest that the skin sciences are not vital. But I value any consideration of skin as something other than a matter to fix (both in the sense of “repair” and of “fixing” or freezing in time).

A few final thoughts:

Readers who want to join the conversation in which this book intervenes have a crucial component of skin to consider in future works, one we don’t read about here: colour, and therefore, race. How, for instance, do white skins feel and experience their own interpretation, or interpellation, as such? What is the quality of the flush, burn, or chagrin that some white people feel when reminded that they are (that I am) white? After all, “Our skin talks even when we don’t; it is not a neutral canvas” (85).

The footnotes are remarkable (sixty across ninety-five pages) and may be my favourite element. They are a crucial part of the book’s “Becoming / dialectic” (89), so much so that the last word in the book is granted to a footnote. And why not? “Feet” have skin too, and any diabetic or cashier can tell you how important it is to take care of them.

If skin is textual, then texts must be skin—or skin-like inscriptions. For a text about skin-etching, Body Work is remarkably unmarked, which is to say that the pages are inked just sparsely. There’s an English 1000 essay to write about how this perfectly captures the book’s ethos, and another to write that argues the opposite.

I began with my own attempt at dermographia, but then noted that Nielsen wants us to “Dig a little” (11). Does this mean I ought not to end with the many skin puns to which my mind wanders now? If even my skin can’t contain me, if even it is porous, permeable, and penetrable, why end with an attempt at corralling myself? Because “becoming” probably doesn’t happen when we summon up our usual tendencies? Because ending with echoes of the alliteration and anaphora of Nielsen’s écriture feminine is more faithful to the book’s impulses? Because faith in the regeneration of skin is a precondition for human existence? Because ending with questions may be a better way to resist closure, to reject the totalizing oneness against which Irigaray and Nielsen write?

Works Cited

Irigaray, Luce. Speculum of the Other Woman. Trans. Catherine Porter. Cornell University Press, 1985.

—. Marine Lover of Friedrich Nietzsche. Trans. Gillian Gill. New York: Columbia University Press, 1991.

Showalter, Elaine. “Feminist Criticism in the Wilderness.” The New Feminist Criticism: Essays on women, Literature, and Theory. Ed. Elaine Showalter. London: Virago, 1986.

Lucas Crawford is a poet and an Associate Professor of English Literature at the University of New Brunswick. Crawford is the author of two poetry collections and the scholarly book, Architectural Tectonics. Crawford’s first poetry collection, Sideshow Concessions, won the Robert Kroetsch Award for innovative poetry and a third collection, Belated Bris of the Brainsick, is forthcoming from Nightwood Editions in fall 2019.

Lucas Crawford is a poet and an Associate Professor of English Literature at the University of New Brunswick. Crawford is the author of two poetry collections and the scholarly book, Architectural Tectonics. Crawford’s first poetry collection, Sideshow Concessions, won the Robert Kroetsch Award for innovative poetry and a third collection, Belated Bris of the Brainsick, is forthcoming from Nightwood Editions in fall 2019.