by Adèle Barclay

In The Argonauts, Maggie Nelson crafts a new kind of text, an exploratory vessel, out of philosophy, theory, art criticism, and memoir to house discussions of motherhood, transitioning, queer family, romance. An innovative work that is exacting and enthralling, The Argonauts harnesses the energy released when exploring gender and generic binaries. Nelson transcends neat categories of autobiography and criticism, picking at the threads of life as a means to get at the knots of culture.

In The Argonauts, Maggie Nelson crafts a new kind of text, an exploratory vessel, out of philosophy, theory, art criticism, and memoir to house discussions of motherhood, transitioning, queer family, romance. An innovative work that is exacting and enthralling, The Argonauts harnesses the energy released when exploring gender and generic binaries. Nelson transcends neat categories of autobiography and criticism, picking at the threads of life as a means to get at the knots of culture.

Ostensibly it’s a story about family—Nelson falls in love, hard and fast, with her sexual and intellectual match, the artist Harry Dodge, and they embark on constructing a familial unit. Nelson becomes pregnant with her son Iggy through artificial insemination while the gender-fluid Dodge transitions at the same time. But really Nelson deploys anecdotes about their baby-making to illuminate questions of homo- and heteronormativity, searching for the points at which queerness and normativity intersect and repel. She recounts marrying Dodge on the eve of Prop 8 in West Hollywood amidst the fake flowers and faux peach finish of a dive chapel and how, afterwards, they celebrated with chocolate pudding on their porch, curled up in sleeping bags with Dodge’s son.

Nelson is keen to note how their forging of queer family is precarious, that it could tip in either direction: “There’s something truly strange about living in a historical moment in which the conservative anxiety and despair about queers bringing down civilization and its institutions (marriage, most notably) is met by the anxiety and despair so many queers feel about the failure or incapacity of queerness to bring down civilization and its intuitions and their frustration with the assimilationist, unthinkingly neoliberal bent of the mainstream GLBTQ+ movement, which has spent fine coin begging entrance into two historically repressive structures: marriage and the military” (26). The book is a historical document of Nelson living and thinking through this fraught time while building her own domicile. This contemporary queer issue—the competing yet simultaneous impulses of normalcy and radicalism—is the friction that motivates Nelson as she pairs domestic vignettes with critical thought.

The Argonauts’ core element is the paragraph, and its sentences are powered by lightning. While Nelson meanders through a vast range of topics by way of paragraphs without chapter or section headings, her striking ability to name the carnal and philosophical currents that shape our cultural moment holds the text together. Nelson is at home with fluctuation, paradox, and nuance, and able to traverse high and low brows to push toward the next kernel of insight or bright crash of frustration. Nelson spars on an erudite level, taking contemporary heavyweight philosophers Žižek and Badiou to task for transphobic pontification—“These are voices that pass for radicality in our times. Let us leave them to their love, their event proper” (79). And in the next breath, her prose pulls you aside to bluntly declare, “I am interested in ass-fucking” (85).

Nelson’s writing is one of the few places where I’ve encountered sexuality, refracted through text, that feels familiar to me. Lovesick and lying on the floor of her friend’s office, Nelson has her friend scour the Internet to determine Harry’s preferred pronouns—it is too late in their courtship for Nelson to ask. Her love is both feral and bookish and she uses it as a flare while navigating theory, art, and literature.

The Argonauts has garnered almost endless praise and attention from mainstream press—NPR, the Guardian, the New Yorker, the New York Times, among others—which is surprising considering Nelson’s interests are fairly esoteric. A student of Eve Sedgwick, she wades with the weirdoes of American literature, George and Mary Oppen, Gertrude Stein, Djuna Barnes, Eileen Myles, CA Conrad, and culls breathlessly from Wittgenstein, Deleuze, Donald Winnicott. The cult success of Nelson’s previous work Bluets, a collection of mini-essays/prose poems about her obsession with the colour blue, hinged partly on the writer, an academic and a poet, finally merging her poetic and scholarly voices. As with Bluets, the popularity of The Argonauts speaks to Nelson’s gift as a writer and thinker—she brings the theoretical references into relief, showing exactly where and how they relate with urgency to emotional and political realities. She doesn’t namedrop; she boils Wittgenstein down to “Words are good enough” (3) in order to explain the reason why she writes.

With its parataxic structure and chain of digressions, The Argonauts is about many things and each reader can glean whatever part is useful to them—it is a book about motherhood, childrearing, love, kinship, queerness, normativity, happiness, twenty-first-century feminism. The title comes from Roland Barthes’s likening of the subject who says “I love you” to the Argonaut furnishing the ship with new parts: “Just as the Argo’s parts may be replaced over time but the boat is still called the Argo, whenever the lover utters the phrase its meaning must be renewed by each use” (5). In this account, name and speech act abide while structure and meaning become utterly altered with time. Nelson’s The Argonauts travels as it speaks, doing the ongoing work of hosting and articulating transformations the queer life accrues.

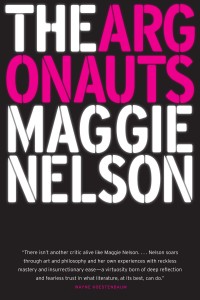

Maggie Nelson, The Argonauts (Graywolf Press, 2015). Hardcover, 160 pp., $23

Adèle Barclay’s writing has appeared in The Literary Review of Canada, The Pinch, Poetry Is Dead, The Rusty Toque, Cosmonauts Avenue and elsewhere. Her debut collection of poetry was shortlisted for the 2015 Robert Kroetsch Award for Innovative Poetry and is forthcoming from Nightwood Editions in 2016.