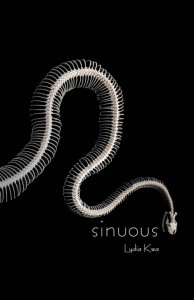

Lydia Kwa, sinuous

Lydia Kwa, sinuous

(Turnstone Press, 2013.) Paperback, 107 pp., $19.95

Reviewed by Chris Fox and Arleen Paré

As avid readers of Lydia Kwa’s fiction (This Place Called Absence, The Walking Boy, shortlisted for the Ethel Wilson Fiction Prize, and Pulse), we were excited to find her second book of poetry, sinuous (her first was The Colour of Heroines). Happily, sinuous is poetry that is unabashedly memoir, which affords the reader an entry into the life and evolution of Kwa, the writer. It is memoir that is solidly polemical, philosophical and political, exploring places and times meaningful to the author. The places are Vancouver, Toronto (and U of T), Singapore, her mother’s kitchen, Japan, a Japanese temple, a psychiatrist’s office, New York. The places are also Kwa’s heart, her mind, states of being, the human condition. The times are now, the last century, the Second World War, ancient Buddhism, 9/11. Far-ranging, yes, but always close to home.

In the book’s preface, Kwa explains that she wrote this poetic series between 1997 and 2011, noting that “sinuous has been [her] companion for such a long time–it has been both a refuge as well as a platform for arguing with [her]self and others.” Book as platform is fairly typical. Many authors employ their writings, their books, as platforms–and Kwa does deploy sinuous in this way. But book as refuge is less familiar. And yet, without a doubt, the reader will sense this when she turns the last page: the experience of refuge; the need for refuge; the very fragrance of refuge permeates Kwa’s poetry. Sinuous is refuge for Kwa as its final lines reveal, “moving out toward the world / surely not a simple case of jettison / from refuge to chaos / in a gasp for living / the breath a blade / slicing through.” It is also a place of refuge for the reader.

Kwa’s writerly concerns are often concerns related to justice, trauma, and/or human relations. Her settings are typically urban, her poetry, primarily intellectual. In sinuous, the tone is personal and psychological, more concerned with dreams and the unconscious (“Everything begins and ends in the basement / unseen, taken for granted”) than is her fiction. But it is also physical. As Kwa writes, “Nothing thinks as clearly as the body.” This is a key consideration: a “sinuous curve uniting / body and mind,” reflecting the aesthetic concerns of “writing the body” that first emerged for lesbian feminist authors in the 1980s and which continue as important pursuits.

The book is arranged as five suites, a pleasing structure that allows Kwa’s poetry to flow through themes, memories, places as though travelling on a river; ideas are pulled along, unimpeded, untitled, doubling back, and curving forward: sinuous. A small coil of snake, a totem, becomes a section divider. Each suite travels approximately 13 pages (a couple wind a little longer) before reaching its destination.

Kwa integrates an impressive range of world thinkers and writers into her writing, which is peppered with quotations from Pierre Janet, Julian Berger, Morihei Ueshiba, Takuan Soho, Gurjit Singh Sandhu, and Carl Jung. At times this strategy heightens the poetic flavour; however, at other times, such intellectual spicing interrupts the flow of the poetics, despite its interest.

Kwa is a poet who takes her writing and her vision seriously. Her most laudable mission seems to be grow the mind and the heart, her own and the world’s too. It is work that aims to liberate the human spirit.