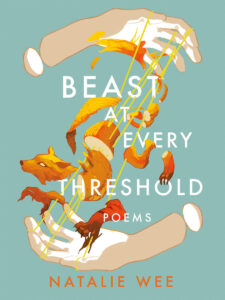

Natalie Wee, Beast at Every Threshold (Arsenal Pulp Press, 2022), 104 pp., $17.95.

In her sophomore poetry collection Beast at Every Threshold (Arsenal Pulp Press, 2022), Natalie Wee offers an exploration of desire, grief, and history with evocative, sensual, and visceral finesse. Reading the collection is like discovering the individual flavours in a delicious meal: each poem stands out on its own while interacting and building on the others in subtle, intricate ways. The layers of references to music, memes, other poets, and queer pop culture deliver a surprising bonus, like an intimate dessert.

Previously the author of Our Bodies & Other Fine Machines (San Press, 2021) and runner-up for the 2020 Pacific Spirit Poetry Prize, Natalie Wee takes risks with her poetry. She plays with form and challenges her readers to explore her poems like a map. Some of the poems in Beast at Every Threshold, such as “Self-Portrait as Monster Dating Sim,” “Self-Portrait as Beast Index,” and “When I Say I Want to Learn Your Mother’s Recipe, I Mean”—which are written like a choose-your-own-path sestina, as a crossword puzzle, or prescribed to be read three different ways—make the reader pause, turn back, and discover something new. While the poems are playful and unique, this sort of experience might be awkward or abrupt for some readers. The potential confusion is worth the unusualness though, as long as a reader takes their time with each poem. They allow for more than one way to read them. Wee gives her audience more than their usual reading experience; her readers have the opportunity to be cartographers.

The collection documents a consuming search for love across language, memory, and history. Wee is a beyond skilled at writing the love poem, whether to a future lover’s potential, a mother’s endurance, or to a grandmother’s failing memory. The attention to minor detail offers us some stunning morsels. Even the relatability of a dog is an eye-opening experience: “I too have cradled my loves to sleep in the arms / of a burning kingdom. I have kissed the ash of dreams & knelt before a door, / obedient, when a given name leashed me by the hair.”

Love is just one side of the coin, and Wee shows how tangled it can be with grief. Even when the speaker of the poem reflects on her love for her mother and grandmother, looking back at their family history is inextricable from misogyny and racism: “I peer through this bloodline & find on the other end / a man wearing a bullet for a face, convinced a girl / is the width of his fist.” In other poems, Wee continues to flip the coin over and over between hollowness and adoration, turning a typically problematic question into something that can bond two individuals as a community: “It’s magic, how / another diasporic darling makes / where are you from sound like sisterhood / instead of a reminder I’m not really from here.” Wee’s poems evoke the pain of racism and hate crimes, but also show the small solace and beauty found in community and family.

Through all this grief, we can’t forget pleasure and intimacy. Not only are some of the poems sexy (and very at that), one of the ways Wee draws in the reader like an old friend or lover is her use of short form and slang, along with pop culture. In “Inside Joke,” a highlight in the collection, it feels as if we’re privy to a good friend’s group chat: “fuck language purists, goodbye only exists bc sum1 wrote god / be with ye in shorthand.”

There are layers upon layers of queer pop culture references, from multiple poems referring to The Legend of Korra, a poem about mishearing a Phoebe Bridgers lyric, a response to the Black Mirror episode “San Junipero,” lines from fellow poets, and more. Beast at Every Threshold is a queer treasure, especially for women and femmes: “what it means to love another woman & bury her / name under a tongue, to peel the sound layer by layer / until each syllable becomes an eel’s wafer-fin / that flounders in a throat.”

A constant thread that weaves through the collection is Wee’s focus on translation and etymology, beginning in the first poem with how the word “humiliate” translates into English as “to lose face.” She shows how a word can easily hop between different meanings, like the slippery slope between desire and shame or love and pain. This is illustrated clearly in the poem “Sayang,” which explores the terror and adoration surrounding a redacted name. The poem scrutinizes the Malay word “sayang” and how it’s affectionate as a noun or verb, but it’s also the saying, “[it’s] a pity.” A single word has several layers to it.

Beast at Every Threshold is divided fairly evenly into two sections: Thresh and Hold, except for one poem, “In Defense of My Roommate’s Dog,” which acts as a sort of stand-alone prequel. While “threshold,” as part of the book’s title, means an entryway, or the point of intensity where stimulation begins to take effect, it’s an interesting word choice to divide. “Thresh” is to separate, typically grain or wheat, or to deliver a blow, while “hold” is to have and to keep, or even reserve or retain. Together or divided, “threshold” is full of intensity and potential of what’s to come, and the decision of when to hold back. Wee is constantly referencing different beasts throughout the collection, whether mythical or real, and yet she evokes them as collected, thoughtful metaphors. Wee truly makes me appreciate the importance of a name and what it can carry. As she asserts, “a name is only lyric / until we know what it commands.”

This is a poetry collection that readers will want to return to again and again in order to sift through the words, delve into the double meanings, and appreciate the absolute intricate success Natalie Wee has created.

…

Michaela Stephen (she/her) is a queer writer based in Toronto, ON, where she works at Second Story Press. She has been published or has work forthcoming in Grain, CV2, Canthius, This Magazine, and The Humber Literary Review, among others. She lives with her cat, Banana Loaf.

Michaela Stephen (she/her) is a queer writer based in Toronto, ON, where she works at Second Story Press. She has been published or has work forthcoming in Grain, CV2, Canthius, This Magazine, and The Humber Literary Review, among others. She lives with her cat, Banana Loaf.