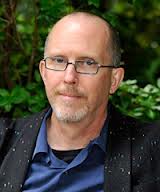

John Barton has published nine previous collections of award-winning poetry, six chapbooks, and two anthologies. He has won three Archibald Lampman Awards, a Patricia Hackett, an Ottawa Book Award, a CBC Literary Award and a National Magazine Award. Born and raised in Alberta, he worked as a librarian and editor for five national museums in Ottawa, where he also co-edited Arc Poetry Magazine and Vernissage: The Magazine of the National Gallery of Canada. John Barton lives in Victoria, where he edits The Malahat Review. For the Boy with the Eyes of the Virgin is his tenth book.

John answered my questions about his latest book during his busy touring schedule, on the train from Ottawa to Toronto.

Andrea Routley: For the Boy with the Eyes of the Virgin is your tenth collection of poetry, not to mention the chapbooks. How does that feel?

John Barton: The book is a survey of thirty-five years’ work and my commitment to the craft of poetry, even of my faith in the vocation I’ve chosen for myself. In a way, the book’s akin to a class or family reunion, where distant relations who’ve not seen each other for decades are gathered together in a party room. I am the poems’ social secretary, who’s made all the arrangements, and now that the party’s started, I have the great pleasure of observing how they interact with one another. Hopefully, it’s a reunion and not a wake.

AR: I liked how the collection was organized chronologically—it’s really interesting to notice how your style has changed over the years. How do you feel your style has evolved? Are these changes the result of conscious choices?

JB: I am of course very close to the work, so it’s perhaps difficult for me to say anything definitive.

I wanted the book to be chronological so readers like you would perceive growth as well as change. I suppose the books each bear testimony to the aesthetic postures I struck at the time of writing them. A Poor Photographer, being the first, is perhaps informed with the egocentricities and insecurities—even with the arrogance—of a beginning poet. Each poem was a thrill to write, as I dove into my newly burnished interest in writing. While writing Hidden Structure, I distinctly remember thinking that I did not want to hide behind the language, so to speak—that is not to bury its subject material, my coming out to myself and others—behind a subterfuge of image, metaphor, and simile and all the other ruses poets have in their poetic arsenal to hide behind. I wanted this long poem—the longest I have ever written—to be both confident and vulnerable as well as articulate, honest and, I suppose, not fearful. West of Darkness is an exploration of persona through the taking on the voice of Emily Carr, and I soon learned that it was very useful to say things about myself through the invented words of another.

[expand title=”More”]

Great Men is the turning-point book, for in it I emphatically stake out the subject that has preoccupied me ever since, which I am sure most readers would identify as the exploration and evocation of gay experience. Notes toward a Family Tree, which comes next, should probably have been published before Great Men. I characterize Notes as my fond farewell to any pretensions I had to heterosexuality (I even wrote a kind of apologia for it as an afterward, and it has turned out to be the most poorly represented book in the selected). In fact I was looking for publishers for both Great Men and Notes toward a Family Tree at the same time—a friend had suggested that I separate a larger manuscript I had tentatively called “Comedians in the Same Desire” into these two collections—and it was pure chance that Great Men found a publisher first. In Notes, I attempted to write about what I arrogantly called at the time “representative man.” It was important to me that its poems “accurately” portrayed something of their time and place to allow readers to see something of themselves in them. I thought a “representative man” (and “woman”) created out of words would hold up a mirror to a shared sense of self. Perhaps Notes was my last attempt to flirt with the very outmoded concept “universality”—which I now view as a pernicious heterosexist construct.

It’s important to recognize that many of these books grew up together. I was writing poems in West of Darkness while I was also writing others that were collected in A Poor Photographer, Hidden Structure, Great Men, and Notes toward a Family Tree. All of these books grew out of my time as a student of Robin Skelton’s at the University of Victoria. He was very supportive of West of Darkness—it was the basis of a special studies course in the last year of my degree. And he even gave me a card about “The Importance of Being Emily,” which of course is an allusion to Oscar Wilde’s play, The Importance of Being Ernest—and I’ve only just realized this instant that Robin might have also been sending me a veiled message that it was okay for me to be gay. Robin left a huge mark on my life as a poet.

Designs from the Interior, which comes next, is perhaps one of my most cohesive books, for its organizing architecture is simple if subtle. An overlay of landscape images (“the suburbs,” “the city,” and “the hinterland”) articulate and interpret the growth of a gay psyche from childhood through adolescence to adulthood. The poems have an urgency to them, I believe, that a resulted from a kind of freefall. I purposely didn’t over think them before I wrote them and wouldn’t let myself to predict where they were going once I began to. This technique of unfolding discovery lends them unpredictability and, I hope, emotional intensity to readers’ experience of them. It is a technique I still use today.

Sweet Ellipsis was greatly influenced by a crash course in the writing of Erin Mouré. I read all her books in quick succession when Arc edited “Who’s Afraid of Erin Mouré,” a special issue on her work in 1994. Something about Erin’s postmodernist methodology morphed my substantially more modernist vision. Many of the poems in Sweet Ellipsis poured out of me non-stop one summer—perhaps the most exciting period of writing in my life. From a technical perspective, this book is where my writing changed most, and reading through the selected, it is where my satisfaction with the book intensifies. The later books could not have been written had I not published Sweet Ellipsis.

In Hypothesis I apply many technical decisions that are not necessarily apparent to the reader. I became very leery of simile and more inclined to metaphor. The opening lines of “Escher” handily encapsulate my feelings on the subject: “One thing becomes another”; poetry is not about one thing becoming “like” another. Though I did not drop “as” from my vocabulary, I suppressed “like” as much as possible, though I allowed it as an adjective and allowed myself “unlike.” I also dropped “that” and “which” as often as possible and limited end-line punctuation to periods, dashes, and question marks. Commas are only used within lines. All these decisions heighten the imagistic intensity of the poems, often making them dreamlike, even visionary, with touches of the surreal. I have been told that the demands I place on my readers in Hypothesis are greater than my previous books.

In Hypothesis, I also debuted something I called “singlets”—poems composed of single-line stanzas that are right- and left-justified. “In the House of the Present” is a good example. Many readers will assume that these blocks of double-spaced text are prose poems, without realizing that every line break was chosen not determined by the margin. It is the negotiation of line breaks that makes singlets poems.

Hymn is the cumulative result of the books that came before it and is a testament to my belief and love or revision. Many of its poems have long histories. “In the House of the Present” took twenty years to write, with many earlier drafts each reflecting an earlier poetics. I consider the book to be almost wholly composed of rescued past failures.

So how has my style evolved? In a few words: in complexity and texture.

I like to think that both oblige the reader to pay more attention.[/expand]

AR: Why did you choose to title this book after the poem “For the Boy with the Eyes of the Virgin”?

JB: A selected is a very difficult book to name. I didn’t want simply to call this collection “Selected Poems,” because that would leave it without an identity; nor did I want to emphasize later work at the expense of what I’d written earlier. “For the Boy with the Eyes of the Virgin” falls near the middle of the book and is drawn from Designs from the Interior, a collection that I published eighteen years ago, at the midpoint of my career thus far. It is also where my voice begins to mature and my subjectivity is confidently and self-consciously queer. Also, I very much liked the idea of a title that suggests that the book is for someone. Readers unfamiliar with the poem may not know who the boy with the eyes of the virgin is, but I am hoping that they might be sufficiently intrigued to find out. Originally, I had hoped to call the book “Guesswork,” but Jeffery Donaldson took that title for a book he published with Goose Lane last year. Initially I was very disappointed, for this had been my working title for several years, but I consider Jeffery’s taking it to be a lucky save.

AR: What is your favourite poem in this collection? Why?

JB: “Favourite poem” leaves me with tremendous latitude for subjectivity and error. The page count of this book constitutes just over one tenth of my total output thus far, so the poems singled out for inclusion could all be considered “favourites,”—each for individual reasons. I’ve just scanned the table of contents and it’s very hard for me to choose a poem as the one I like most. There are many that I am very satisfied with— “The Pregnant Man,” “Hidden Structure,” “Grey,” “At Lindow,” and “Days of 2004, Days of Cavafy”—because they each represent breakthroughs in theme or technique. Or I remember them as being pleasurable to write. “Saranac Lake Variation” is always the one I say is my best poem—but is that fair to the others? I like how it moves from the personal to the political, how it has ruptures and shifts in the voice, how it evokes place, how it preserves the memory of the man to whom it is addressed, who was a very sweet and troubled person, whom I loved very much, and who sadly is now dead.

AR: There are several poems from the point of view of Emily Carr, from the collection West of Darkness: Emily Carr, a Self-Portrait. The publisher, Nightwood Editions, summarizes the content of this book as an exploration of “the role of love in contemporary society, the complexity of gay experience, the persistence of homophobia, the reinvention of the idea of family, and the fear and courage that AIDS engendered and how it continues to shape the search and attainment of intimacy.” Can you tell us why you chose to engage Emily Carr in this exploration?

JB: If you were to go back to the original edition of West of Darkness, which was published by Penumbra in 1987, you would read in my afterward that I considered its publication as the end of my apprenticeship as a poet—a foolhardy assumption, I feel in retrospect, for I am still apprenticing at my craft. Nevertheless, it was a watershed, for it was an ambitious project for a young poet to pull off. How does it fit with my so-called gay-focused aesthetics, a question that I’ve been asked before? The simple answer is that queers are perpetual shape-shifters, perpetual-motion machines. I always say that Emily Carr is my drag identity, one I am still growing into as I become older, an aging artist like her whom I hope will meet life’s challenges equally well.

Before the advances of gay liberation, we needed to pass as straight to survive and either masqueraded as good husbands and fathers, if we were fearful, or as dapper bachelor uncles who kept to themselves. Then once we began to feel bolder, we became clones, leather men, Lesbian Avengers, divas, and so on. Not for me the feathers and sequins of younger drag queens, which I’d now find humiliating to assume, mutton dressing as lamb. I am much more suited to hairnets, painting smocks made from flour sacks, and sensible shoes, with a monkey on my shoulder and a dog-eared volume of Walt Whitman at hand, and a few intact ideals. Also, all poets worthy of the name are willing and able—even predisposed—to address diverse subjects in their work. Very early on, Emily Carr was one of mine. It would have been impolite of me not to include her in the book.

AR: I loved Vaughan’s introduction. He writes “there is no such thing as a cowardly John Barton poem,” and that you were “‘out’ long before it was safe, out in an era when publishers would print any old sweet cream and teatime-recipe poem . . . before they’d letterset a simple love song between two fellows.” As prolific an editor as you are an author, you have an expert’s view of publishing today. How do you feel the literary landscape has expanded for queer writers? How is it limited? What are the challenges for queer writers today?

JB: When I compiled Seminal: The Anthology of Canada’s Gay Male Poets with Billeh Nickerson, I noticed that fully half of the poems had originally been published between 1990 and 2007, a short period of time in comparison to the much longer period of time over which the previous half was published, years during which poets were not able to be as frank about their sexual orientation. I not sure why 1990 seems to me to be an apt fulcrum in Canadian queer letters; and it may only be a chance and meaningless observation. However, more and more legal protections for gays and lesbians were put in place through the seventies and eighties—sexual orientation was enshrined as a protected category in the Canadian Human Rights Act and by extension in the Charter of Rights and Freedoms in 1992—so perhaps queer writers felt freer to speak openly about their experience. Also, by 1990, the need to write about AIDS and rally round its victims had become very urgent. In the United States, Paul Monette published Borrowed Time, his memoir about the AIDS death of his long-time partner, Roger Horwitz, in 1988, and in 1992, his second memoir, Becoming a Man, about his life in general and his sero-conversion in particular, won the National Book Award for Nonfiction. Writing about AIDS made queer writers bolder, not only to comprehend the disease, but to preserve their experience in memory. The eighties and early nineties are very marked by this remarkable literature of loss.

[expand title=”More”]

Starting In the late 1990s, American novelist and social critic Sarah Schulman has written extensively about how larger commercial publishers began to drop their queer authors in a kind of social engineering in face of declining sales and worsening bottom lines. If you pick up a recent copy of The Gay and Lesbian Review, you’ll notice that the vast majority of the books it reviews are published by small or academic presses. Authors who used to publish with houses like Crown, Harper Collins, etc. are now with presses like Arsenal Pulp and Cleis, to name two examples. Many seemingly self-published authors also purchase advertising space in magazines like The Gay and Lesbian Review. This move to small press and self-publishing may suggest a corresponding loss of access to readers. Small houses don’t have large promotional budgets. As a poet, I find nothing unusual in this. However, with the rise of e-books, I think queer writers have great opportunities before them.

How do these observations translate into an understanding of queer writing today? Despite the challenges of the present publishing environment, there are simply more queer writers writing now than before and their accomplishments stand on the shoulders of those who came before. They may write about gay subjects or they may choose to explore something different. I’d like to believe that, whatever they write about, their queer sensibilities inform their poems, stories, and plays. [/expand]

AR: Have these changes influenced your writing?

JB: It’s hard for me to be objective about my own work, but I will say that it has been informed by the AIDS crisis. Also, as a poet, I have ridden the ups-and-downs of publishing like everyone else. The simplest way to combat them is to write well.

I think an important influence on queer writing has been how it is read. How mine has been read is telling. Critiques written by straight reviewers of Great Men, which I published in 1990, in comparison to those by gay reviewers, show a difference in focus. Straight reviewers wrote almost exclusively about the book’s love poems, which were largely ungendered, while gay reviewers narrowed in on the poems with overtly gay content. Each set of reviewers placed me in a kind of ghetto; the former, while acknowledging that I was queer, whitewashed me; the latter emphasized particular hues. Readers see what they wish to see. I’ve aimed to write on gay themes throughout my career by applying the most accomplished poetics that I can muster, expressing a gay subjectivity that queer readers might see themselves in and with a technical finesse that all readers of poetry can respect. I make myself sound like a spider spinning a well-executed web to lure in my readers, only to stupefy them with the full force of my queer-laced content.

[expand title=”More from John Barton on the publication process“]

AR: How did this book happen?

JB: Only two of my nine previous books are now in print. Arranging rights to poems from a book that is still in print can be tricky and can even involve permissions that must be paid, so when ECW and Anansi agreed to return the rights to Designs from the Interior, Sweet Ellipsis, and Hypothesis to me in 2008, the timing seemed right to compile a survey representative of my career thus far. Closer to the time of publication, Dundurn and Brick, graciously granted to reprint poems from West of Darkness and Hymn—both still available—without charge.

In 2008, based on advice from friends, specifically Shane Neilson, I sent query letters, accompanied with a selection of reviews and articles about my work, to a number of publishers to see if any of them would consider publishing such a book, and in the spring of 2009 Silas White at Nightwood was the first to express interest. Silas eventually offered me a contract in January 2011. Some would wonder why it took him so long to make a final decision, but a volume of selected poems is a different kind of book. Unlike collections of new work, such a book is not eligible for Governor General’s Awards—and because awards are one of the few true profile-raising marketing tools available to the publishers of poetry, a selected can be perceived as having a built-in liability for invisibility. Publishers may also fear that potential readers would characterize a selected as “been there, done that,” and not want to buy it. You’d have to ask Silas, if he had any of these anxieties about my book, but I can only guess that he saw merit in the enterprise of publishing some of my best work in a single volume. I also had the luxury of being in no rush for a decision, so I never felt the need to hurry him along. Decisions need whatever time they require to be made, and I always take the long view in such situations. When Silas made his, I believe he did so with few or no doubts. I am very grateful to him.

AR: How did you make selections? Is this collection meant to be representative of your work, or is there a particular story you wanted to tell?

JB: Over the month of April in 2010, James Gurley, an American poet in Seattle, who’s one of my closest friends, helped me go through each of my books in order of publication. As I remember, we both came up with lists of candidate poems from each book and carefully whittled down the combined list to a representative sample of poems, progressing to the next book only after discussion of the one then under discussion had concluded. I like to call the 200-page result the “rough cut” of what became my selected, and this is what I sent to Silas in 2011, after he decided to accept the book. What amazed me at the time—and amazes me still—is that Silas agreed to publish my selected without seeing a manuscript for it first. He must have based his decision in part on the reviews I had submitted along with my query letter in 2008.

In any case, the terms of my contract, which I received in August 2011, specified that I next submit a 120-page manuscript that fall, so I spent the next month paring down the rough cut by 40%. The process also involved a few substitutions in favour of some of Jim’s and my initial selections, and I asked Jim to take a final quick look at the shortened manuscript before I sent it to Silas. In May 2012, just before the book was sent to Carleton Wilson, Nightwood’s excellent designer, for layout, Silas proposed a few more changes to the selection, so more poems were withdrawn in favour of others that were added—by this time Silas had familiarized himself with my previous books. I was particularly pleased with his input, for poems that I always liked very much—“Confidential” and “Touch-Screen” come to mind—were brought into the book. I can’t now tell you which poems Silas and I dropped at this stage, which is a sign that I don’t miss them.

AR: Did you have a hand in selecting the cover image? Can you tell us why this image was chosen?

JB: Nightwood gave me great latitude. It was very important to me that the cover artist be queer, so I approached Victoria artist Miles Lowry; his work had also graced the cover of my 1984 book, Hidden Structure, as well as illustrated several of its inside pages. I emailed Miles a copy of the manuscript, and a while later, he replied with the cover image and nothing else. It worked very well with the book’s title, and I feel that Miles had a strong intuitive sense of what would work best. Within, which is a photo he took of one of his own sculptures, might be a piece of antiquity unearthed during an archeological dig. That the figure’s eyes are closed makes the image especially powerful. It suggests a kind of meditative interiority I hope the poems inside the book also have.

AR: What is next for you?

JB: I am working on two projects very slowly. One is a book of formal poems, which I am calling Strange Meeting—pantoums, glosas, quintillas, sonnets, and other verse forms that cover a very wide range of subjects from Benjamin Britten to global warming, with a few one-night stands in between. The second book, Contrapposto, daunts me. It is an extended documentary poem about painter Paul Cadmus, photographer George Platt Lynes, and ballet impresario Lincoln Kirstein, all gay men who knew one another and lived in New York through the twentieth century. The book looks at the [male] body in visual art, ballet, and photography from social, aesthetic, and political vantages. I’ve been working on this book off and on for ten years and published many of the existing poems in magazines. Eight of the ballet poems have also been collected into my recent JackPine chapbook, Balletomane: The Program Notes of Lincoln Kirstein; I’d like to collect a handful of the thirty Cadmus poems in a similar chapbook sometime in the immediate future. My first goal is to finish Strange Meeting in the next year. I don’t mind if Contrapposto takes another decade. I benefit from knowing that no one is waiting for it, so I can take all the time I want to get it right.

[/expand]