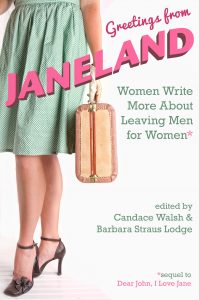

I came out while reading Greetings from Janeland: Women Write More About Leaving Men for Women, edited by Candace Walsh and Barbara Straus Lodge. It’s the 2017 sequel to Dear John, I Love Jane, which was released in 2010. I hadn’t read the first book when I read Greetings. The fact that it took an anthology of essays by queer women to inspire me to come out at the age of 52 says a lot about the contributors’ empowering combined force. Not that it’s unusual for women to come out as queer later in life, for reasons of sexual fluidity, gender identity, and/or a life-long struggle of facing repressed or closeted sexual orientation.

I took my time savoring and processing the book. With a few essays left to read, I came out to my siblings (I let my son know I was queer a year ago and a few close friends before that). A couple of weeks later, I came out to friends on Facebook. And here I am making my first public statement: I am queer, bisexual, maybe all gay, and it’s okay not to know if I’ll ever want to be with a man again.

Each story of leaving a man for a woman in Greetings is unique. Journeys include growing up in an oppressive religious family, a long marital entrapment inside domestic violence, surprising oneself with sudden dreams about women, and sometimes, even, the writer ends up with a man after all or is happy being alone.

Several of the writers are returning contributors from Dear John, I Love Jane, offering updates on their original stories or a matured perspective on being queer. And many of the essays touch on the current political climate, the history of LGBTTQI rights, the impact of the Pulse nightclub shooting, the mustering of support for each other in the queer community, and overcoming fear. Queer literature is often quoted as inspiration, including more than a couple references to Adrienne Rich. Emily Withnall reminds us of Rich’s much-needed line: “When a woman tells the truth she is creating the possibility of more truth around her,” echoing loud and clear across both queer women advocacy and today’s #MeToo movement.

The narrative stories with specific scenes and dialogue impacted me more than the abstract essays summarizing events and ideas. Each essay adds a vital voice, but the more concrete the experience, the more powerful, and the quality of writing does vary from essay to essay. While all the writing is good, some of it is outstanding, making me wish all the essays reached the same level of literary strength. But the variety of voices and perspectives help make up for this loss.

Leah Lax’s essay “Birth Day” is excerpted from her memoir Uncovered: How I Left Hasidic Life and Finally Came Home. In a lush scene crafted for the five senses, Leah is walking in the woods at dusk before kissing a woman—her companion on the walk—for the first time: “Her softness is a sound that fills my ears. Compared with this, memories of Levi are paper that rustles and scatters.”

The immediacy of the details is unforgettable, as are the scenes from perhaps the best-written essay, featured first in the collection, “Sir, May I Have a Pack of Marlboros?” by BK Loren. She has the rare gift of making her summary statements equal in power to her fully developed scenes. She knows where to weave in the broader ideas. Between two scenes building up to her first relationship with a woman, she lists in bullet points what she was known for in high school. First on the list: “My goal in life was to fake my way into a mental hospital. I believed I’d be happy there. In the outside world, I felt straight-jacketed,” summing up how so many of us have felt spending years and often decades not coming out even to ourselves. Loren keeps the reader’s emotions in tune with her narration, and by the end of the essay, we feel her revelatory sense of confidence in love and know that we, too, can make it there if we haven’t.

Each essay gives the reader a different glimpse into the agony and joy of a woman discovering and accepting her own desire. Even the more abstract essays pack a punch with quotable lines as in K. Astre’s “Unexpected Expedition”: “I didn’t think there was much else to ask for out of a relationship because I didn’t know what heights my senses could scale.” And some of the writers portray sensuous scenes that would shake most queer readers with a slumbering libido awake—genuine intimacy that doesn’t feel pornographic. So that’s what I’ve been missing.

The book is not without humor as well. Joey Schultz-Ezell writes, “My hair knew I was gay before I did” and, a few pages later, she says her queer family calls itself “The Gaydy Bunch.” And when a writer lands on a perfect simile or metaphor, it helps this reader finally make sense of how I’ve felt for so long. There’s a reason I’ve felt straight-jacketed inside my life. For me, that reason was not accepting my queer identity and, before that, not even being aware of it. G. Lev Baumel writes, “My life has become like an itchy wool sweater that’s shrunk in the wash. No matter how hard I wrestle to fit into it, it’s too uncomfortable.”

In “Strong Like Her,” StarMcGill-Goudey calls her mother’s bible “that ancient book of oppression and horrors.” Cassie Premo Steele’s essay “Pregnant with Myself” uses poetic repetition, ending sections, for example, with a sentence containing the word “good” in different contexts, the meaning of the word ever-evolving with her changing perspective.

After having already come out to my family and close friends, I posted to my Facebook friends on National Coming Out Day this October, with a photo of a lone fishing boat and the stunning mountains across the water: “I’m a queer person all about being alone for now in Homer, Alaska.” Thank you, writers in Janeland, for helping me say it.

Greetings from Janeland: Women Write More About Leaving Men for Women, eds. Candace Walsh and Barbara Straus Lodge (Cleis Press, 2017). Paperback, 240pp., $24.95.

Rebecca Snow’s debut novel, Glassmusic, was released from Conundrum Press in 2014 and shortlisted for the 2015 International Rubery Book Award. She was awarded a fellowship in poetry for the 2015 Seaside Writers Conference, and her creative nonfiction and poems have appeared in The Guardian, Progenitor, Rattle, and elsewhere. Snow teaches creative writing for the University of Alaska/Kenai Peninsula College in Homer, Alaska.