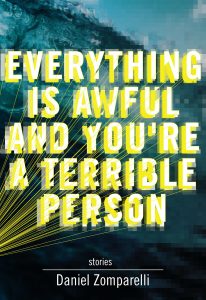

Local snowbird, poet and fiction writer, and editor of Poetry Is Dead magazine Daniel Zomparelli’s new book Everything Is Awful and You’re a Terrible Person was released this year with Arsenal Pulp Press in Vancouver to rave reviews, deservedly followed by a shout-out from the New York Times. Matthew Walsh interviewed Daniel for Plenitude magazine about his new book, ghosts, creating visual art, and how he balances comedy with tragedy in his writing.

Matthew Walsh: This book takes an experimental look at what a writer can do with short stories. The stories interlock in significant and subtle ways. We follow Ryan and others through Everything Is Awful and You’re a Terrible Person, and we do it through short pieces, like “Date: Luvcub,” and longer stories, like “Tongue Out Smiley Face.” Was this a format that you started out with in mind, or something that developed out of your writing process?

Daniel Zomparelli: This came about relatively quickly after I had finished a handful of the stories. I wanted to see other characters come back and wanted to write sequels to stories. Ryan’s narrative is when I really got into it. I wanted to tell the story of someone but only through dates. It was originally just one story (and I would argue it still is), but I spread it throughout the book as a way to bring the reader back to a specific narrative. I wanted the reader to check in on different characters as they were going. It felt more reflective of the way a gay community can feel small and intertwined.

MW: The title of the collection is Everything Is Awful and You’re a Terrible Person, but not everything is awful. There is a lot of comedy in the book, too, like the relationship between characters in the title story and their journey to the Maritimes, or the many interactions on apps in the book. Maybe I am terrible, but I laughed. I was also touched by them. It seemed like the sadness was easier to take with some comedy in it to even it out—like in the Luvcub story. Was that something you were focused on while you wrote?

DZ: I have always loved dramedies. Comedy can be a nice valve release so that when there is so much sorrow going on, [readers] get a break and can go in for more. Also, comedy is what I enjoy most. After I had sent anyone my stories, they would give feedback but I would always ask “okay, but did you laugh?”

A lot of these stories were written out of grief after the loss of my mother. The title story has a couple of people who represent the friends who carried me in those times. I was making a lot of mistakes but friends acted like bumpers in bowling so that I made it down the lane (lol, I don’t know why I’m using a bowling reference). Having the safety of friendships where you can joke about anything is a lifesaver for me, and that’s what I was hoping to get at in some of the stories.

MW: What was so memorable for me as a reader was the way the characters talk in the book. The dialogue is so natural that it was easy to imagine these people, and a lot is communicated even in just asking do you want to spend the night?—a line that is sort of a little thread throughout the book. Was it easy to get dialogue right, or get it to do more than just being something that is said?

DZ: I have a pretty bad memory for a lot of things, a lot of basic things. I once tried to remember the word “carrot” and had to say “it’s like orange but also vegetable?” But the one thing my brain locks in is dialogue or conversations. It’s a very annoying trait to have because no one likes to hear “that’s not what you said,” but it’s what I enjoy writing and it feels easy to get at. I’m shit for descriptions (see: orange vegetable), but dialogue I feel confident about. When writing I had a lot of the conversations between gay men swirling in my head and so a lot of it went into this book. “Do you want to spend the night?” is a common one, because it is a commitment beyond sex. What is the desire for staying the night, what intimacy will that hold, all of those questions come into play so it’s a weird moment to deal with. Someone wanting to be alone and the other wanting company can be tough, it can feel like a form of rejection even after something as potentially validating as sex.

MW: Technology is a component to how you tell some of these stories. For instance, in “Blocked” the main character’s phone and the interactions on the phone tell most of the story—through text messages and #hashtags. You could have told this story a bunch of ways. Was using the phone something you always had in mind as a plot device, or did it come through some other way, like through developing the character?

DZ: I always had this in mind for the book. What we text, what we post online, it’s all a story that we present. But I also wanted to show what the potential story was behind those things. We follow strangers on Instagram and Twitter and we think we know their lives, but we have literally no idea what is happening beyond their posts.

MW: I loved what you did promoting your book over Twitter, with all the gifs and fakeboyfriend.net. It really tied into the themes of the book and it was cool to see the teasers for it, because so many of the characters are on their phones. How did you get the idea to promote this book in such a unique way?

DZ: I love creating visual stuff. For each of my earlier books I was able to make some visual poetry along with the text, but this book had none. So for the marketing, I found a way to incorporate that. Phones can be a horror story of emotions, so I wanted the glitched images to feel that way as well. And also to show that phones are weird magic boxes. You can have these text message exchanges you post online, but glitching them felt like a reminder that anything posted can be a false narrative. I did feel bad that everyone thought my boyfriend was writing these intense messages (each of the screen grabs was from a “Boyfriend” that was a character from one of my stories).

MW: In between the longer pieces you have a few short poem-like moments here and there. While you were working on the book did you take breaks from fiction to write poetry, or did writing some of these stories inspire any poems?

DZ: The only break I took was to write Rom Com with Dina Del Bucchia. It was mostly to get me back to writing consistently and it helped. After I finished that book, I stopped writing poetry. I’ve written a thing or two for commissions, and there’s a few poetry-like pieces in here that are actually from a handful of years ago, but I haven’t written poetry in a long time. There’s so many great poets out there that I just don’t feel up for the challenge yet. These new poets are so good, beyond my skills, and I can’t keep up. And I get to have the pleasure of being a reader without thinking of my own work. It’s really nice.

MW: Where do you go, what do you need, when you are sitting down to do a long writing session?

DZ: I don’t do long writing sessions. I’m a super slow writer so I only write about an hour or two at a time. The only thing I really need to write is a deadline. If I don’t have one, I just write a sentence or two at a time, or just write down notes. I’m much better at playing Bubble Witch 3 and fav’ing Instagram photos of puppies/cute babies than being a prolific writer.

MW: Ghosts play important roles in these stories, and the collection opens with a ghost story, in “Ghosts Can Be Boyfriends Too.” Have you ever had a weird experience you could say was caused by a ghost?

DZ: Ah, yes. I have a lot of weird experiences with ghosts. I always felt protected by a ghost when I was younger. This is probably an intense thing, but my sister passed when I was young, and she was always the person I would go to when I was having anxiety nightmares. These nightmares were intense and made me feel like I was going to pass out. I would run to her bedroom and she would always make me feel protected. After she passed away, I was very confused and wouldn’t go to her bedroom anymore. We had this very long dark hallway that I was certain was haunted. At the end of the hallway was my mother’s room. After my sister passed away, I would have to brace myself and run as fast as possible to my mother’s room. It felt safe, but didn’t feel the same. After that, I used to hear things being moved around in our home, and even when we moved I had an instance where someone knocked hard on my bedroom door, but no one was home and the alarm was set. There was a lot of weird instances like this that I won’t bother explaining, but it always felt protective rather than scary. I guess that as a kid, ghosts are easier to carry around than grief.

Matthew Walsh is a award-winning poet and short story writer whose work has appeared in journals across Canada and his interviews can be found on Maisonneuve, Prism international, and Plenitude. He’s @croonjuice on Twitter