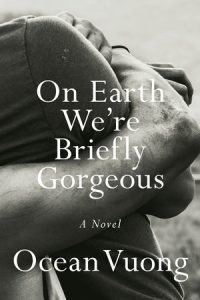

Ocean Vuong, On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous (Penguin Random House, 2019), 368 pp., $28.00.

In his first novel, On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, the poet Ocean Vuong creates scenes of magisterial beauty through a heartfelt and earnest exploration of grief, desire, pain, and joy. The novel, written as a letter to the protagonist’s illiterate mother, is remarkable for its verbal and imaginative daring in exploring scenes of incredible vulnerability and sensuality.

By structuring this book as a protagonist’s letter to his mother, Vuong is able to mine an incredible amount of ethnographic detail in the form, and for the sake, of fiction. Vuong traces his protagonist’s (nicknamed Little Dog), his mom’s, and his grandma’s journey (named Rose and Lan, respectively) from Vietnam to New York to Hartford, Connecticut. We are briefly taken back to an imagined Vietnam when Little Dog’s family had to flee the war that was bearing down upon them. We get scenes of a young woman and a girl by a dirt road, their city on fire. But this telling feels jostled and hurried, as if we are urgently trying to get elsewhere. It does not feel like the narrator (or the author?) wants to spend time telling us about this point in his life.

The elsewhere the narrator arrives at is a pained and painfully erotic story of Little Dog’s first love, in the form of Trevor, a “hick white boy” from the backwoods of Connecticut who lives with his father and works in the tobacco fields with Little Dog. Trevor shoots and skins raccoons, drives a pickup truck, and hates himself for being queer. Vuong intentionally reveals Trevor as an unlikeable character, yet the narrator’s articulation of his love for Trevor makes everything bloom:

I wanted more, the scent, the atmosphere of him, the taste of French fries and peanut butter underneath the salve of his tongue, the salt around his neck from the two-hour drives to nowhere and a Burger King at the edge of the county, a day of tense talk with his old man, the rust from the electric razor he shared with that old man, how I would always find it on his sink in its sad plastic case, the tobacco, weed and cocaine on his fingers mixed with motor oil, all of it accumulating into the afterscent of wood smoke caught and soaked in his hair.

There are two beating, pulsing hearts in this novel: one, the tragic love story of a racialized queer migrant surviving generations of trauma who falls in love with a poor rural white boy, a story that touches on race, class, the opioid crisis, the housing crisis, urban/rural divides, the way late capitalism creates excess bodies which cannot be accommodated into its circuits of wealth. The other tells the story of two generations of Vietnamese women, both of whom barely survived (that word feels indulgent or excessive here, as I’m not sure if they survived or not, or if what they survived can be accurately captured by naming it survival) a war whose aftereffects still burnish the landscape and whose violence grows inside their bodies like cancer.

For a poet who has previously demonstrated a keen ability to cohere all kinds of valences of violence through his tensile grasp of the English language alone, these two stories never convincingly come together. The poetic resonances here are not able to bridge these disparate worlds. Instead, so many of the stories in this book feel like stumps: stumps that lead nowhere; stumps that end abruptly; stumps that begin to flower before being cut off; cut down. There is very little conflict here, much of the narrative drive of the text coming from how these stories sit in proximity to one another, revealing new, refracted meaning through context and placement. Sometimes this works but, more often than not, it feels as if we are reading fragments of a whole that don’t want to fit together.

Little Dog’s father feels like an aching absence in this text, one so painful the narrator never fully faces it. We only get tiny whispers of the narrator’s father, mostly in the form of violence. There are snippets of domestic violence: a man beating a woman, a house on fire with our young narrator hiding under a table. We get Little Dog on a turbulent plane with his mother, attempting to get back with his father and Little Dog convinced that it should be like this, that the plane should feel as if it is shattering. We get the whole family, Little Dog, Rose and Lan, driving to Little Dog’s aunt’s house to save her from a violent alcoholic man, only to find that they have come to the wrong address. These scenes communicate a notion of family as primarily a site of violence and pain. But there are also incredible scenes of tenderness and care between Little Dog and his matriarchs.

Unfortunately, the conceit of a son writing letters to his illiterate mother doesn’t fully work. So much of the narrative drive in this text comes from Vuong’s achingly tender portrayal of the relationship between mother and son, but many of the chapters (especially ones that relate incredible scenes of sexual intimacy) feel as if they are addressed to anyone but Little Dog’s mom. Vuong makes this clear directly: “the very impossibility of your reading this is all that makes my writing it possible” and “I am writing to reach you—even if each word I put down is one word further from where you are.” But acknowledging the limitations of his address do not make those limitations disappear.

Indeed, this epistolary form overdetermines the telling: too much of the profundity contained in this novel feels unearned and far too precious. There are lines that read as if they have arrived too early, as if the burnt truth of pain that created them was never fully shown to us.

Perhaps that is too much to ask of an author who has already given us so much, but this is how it felt putting down this novel. There is so much incredible story here, the telling itself never feels as if it fully accounted for it. Still, the linguistic form holding this story is worth reading, if only for the beauty of its language alone.

Asam Ahmad is a writer living in Tkaronto. His first collection of essays is forthcoming from Between the Lines Press.

Asam Ahmad is a writer living in Tkaronto. His first collection of essays is forthcoming from Between the Lines Press.