Reviewed by Evelyn Deshane

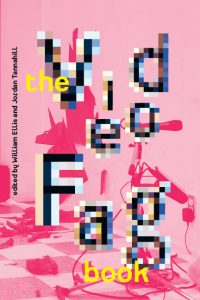

A black hole infiltrates much of The Videofag Book, a collection edited by William Ellis and Jordan Tannahill about their time running the Videofag art space in Kensington Market, Toronto. Comprising an introduction by Tannahill and Ellis, a roundtable conversation, love letters, a play, poetry, and over a dozen photos, The Videofag Book is meant to represent four years of performances while also summarizing the main ethos of the project as a whole. In effect, The Videofag Book strives to represent the empty space of the stage where art used to be by showing the reader so much of what came before. Only through this intense cacophony of voices and blasts of colour do we get a sense of what used to be on Augusta Avenue.

A black hole infiltrates much of The Videofag Book, a collection edited by William Ellis and Jordan Tannahill about their time running the Videofag art space in Kensington Market, Toronto. Comprising an introduction by Tannahill and Ellis, a roundtable conversation, love letters, a play, poetry, and over a dozen photos, The Videofag Book is meant to represent four years of performances while also summarizing the main ethos of the project as a whole. In effect, The Videofag Book strives to represent the empty space of the stage where art used to be by showing the reader so much of what came before. Only through this intense cacophony of voices and blasts of colour do we get a sense of what used to be on Augusta Avenue.

Before I go on, I must confess: In spite of living close to Toronto, I never saw anything at Videofag. Not until I saw the bright pink cover on publisher Book*hug’s website did I realize this art space existed—but the moment I read the write-up, I knew I had been there. At some time, in some other place, I had experienced Videofag without actually being there—which is to say, I have felt that strange mix of queerness tangled through a complete obliteration of private and public space—which is to say, again, that I have felt nothing in spite of being surrounded. That’s what The Videofag Book book is about: nothing, and everything, and the inherent confusion in these states of being.

Videofag is located in a black hole of time and space, permeated by a perpetual sense of not being there tomorrow because the rent is high and they’re artists. When William and Jordan move into the former barbershop, they paint over old hair; this fact is mentioned several times in the collection, especially in the roundtable discussion “House of the Cool Parents.” Many of the artists in that discussion claim that the hair is still visible, as if the walls know that Videofag itself will eventually be painted over.

These contributors praise this sense of queer temporariness, since it frees Videofag from the time-as-productive model. Knowing that this show will end means that they can enjoy it for what it is now, and not for what it could mean to a future board of directors for the Art Gallery of Ontario. Embracing the lack of stability means that every single performance (be it the play All Our Happy Days Are Stupid or the Sissy Boy YouTube Night) has a sense of urgency about it. Urgency is what gives photos in the book a celebratory attitude. Each image makes me wish I was there; for those who were, these images put them back into that frame of time with a glimpse. It’s so fitting that the review package for this book came with a postcard of its cover, because each one of these photos shouts “wish you were here” at the highest volume, representing a time and place so succinctly while also making it utterly transitory.

The cry of “wish you were here” is also melancholic. I look at this transitory environment and love everything it embodies, but it also fills me with dread because it is now over. Though Jordan Tannahill and William Ellis have gone on to other things, as have many of the other artists who participated in the collection, there is a permanent sense of longing that imbues each one of the testimonials. The play A Man Vanishes, written by Greg MacArthur, represents this sense of dread the best. For me, it is the standout work in the collection.

A Man Vanishes, performed at Videofag from March 10 to 20, 2016, includes Jordan and William as both actors and characters and documents the last days of a man who vanishes through others’ stories of him. While piecing together the man’s former life in hopes of finding his future, we also get constructions of Jordan and William and their art space project. In one scathing monologue, a friend named Jen says that Jordan and William’s perpetual need to have their lives on display through Videofag is “desperate” and “pathetic” and most of the time “they look sad.”

This is the first time that we hear direct criticism of Videofag’s goals. Collapsing the boundaries of private and public is not always triumpphant or celebratory; it’s annoying and upsetting and invasive to have people walk through your home and your bedroom while dressing for their play. It strains your sense of self and your relationships. Indeed, Jordan and William were boyfriends when they opened Videofag, but by the time it was over, they had broken up.

Though the breakup is mentioned on the back cover—like VideoFag’s eventual ending—there is little closure around their relationship. Was their breakup as triumphant as Aisha Sasha John’s goodbye party poem? Or was it quiet and unsettling, like MacArthur’s description of the man vanishing? I found myself filled with questions about their private lives—which, of course, they have the right to keep private. They do not have to write an exposé on their love life in order for their art space project to be seen as valid—but, as Jen reminds me in the play, they also did put their lives on display. I want to witness their life, but so often, it feels like I’m looking at a void.

Ultimately, I think Eric’s monologue about black holes in A Man Vanishes sums up Videofag the best. When he says that black holes can’t been seen—only felt—it is clear that he’s talking about William and Jordan’s project: “Can you imagine […] being able to asphyxiate light?”

Videofag left a mark in people’s imagination, but I’m sure it also left a physical mark in the practice space itself. No matter who moves in next, they will surely paint over glitter, like the former barbershop’s hair, thereby allowing Jordan and William to asphyxiate the light a little longer.

The Videofag Book., eds. William Ellis and Jordan Tannahill (Book*hug, 2017). Trade paperback. $23.00.

Evelyn Deshane’s work has appeared in Bitch magazine, Briarpatch, and Strange Horizons. Evelyn (pron. Eve-a-lyn) received an MA from Trent University and is completing a PhD at the University of Waterloo. Evelyn’s recent project #Trans is an edited collection about transgender and nonbinary identity online. Visit evedeshane.wordpress.com for more info.