Reviewed by Asam Ahmad

Near the beginning of Hanya Yanagihara’s A Little Life, one of the main characters witnesses his roommate in physical pain. Instead of trying to comfort his friend, he goes to the bathroom to start tidying up, waiting for the pain to subside: “he did what they had all learned over the years to do when Jude’s legs were hurting him, which was to make some excuse, get up, and leave the room, so Jude could lie perfectly still and wait for the pain to pass without having to make conversation or expend energy pretending that everything was fine.”

Despite the initial turning away, this is not a novel that allows us to look away from pain, physical or psychological. A story about four male friends—Jude, Willem, JB, and Malcolm—who move to New York City after college to pursue their dreams, the novel is structured like a piece of ombre fabric. What initially seems like a sunny narrative of upward mobility turns out to be far darker and more terrifying than anyone could have anticipated. The novel simultaneously moves into the future while reaching into the past to reveal Jude’s horrifying truths. But this is also one of the biggest strengths of the novel. Jude’s story, as we learn in greater detail as the narrative progresses, is one that is almost impossible to hold without feeling intense discomfort and a deep yearning to look away.

Yanagihara employs familiar codes of a New York City post-college narrative to lull us into a false sense of comfort, using various aesthetics to distract us from the pain we are about to witness. There are lengthy and gorgeous descriptions of art and food; sometimes they seem to crowd out the story itself. I suspect one of the reasons the novel works, and what accounts for its unanticipated success, is the way in which it intermingles the abject and the sublime with such terrifying beauty and precision. Yanagihara has spent the last two decades pursuing a career in New York City’s literary world, using her knowledge of the art scene to brilliantly convey current trends.

This sleight-of-hand structure, in which stories that the narration implicitly suggests are not a part of this world slowly unfurl themselves, is used to present a narrative of trauma that is so clear and prescient it is impossible not to be deeply affected by it. As the novel develops, the narrative spends more and more time on the enigmatic Jude St. Francis. Towards the end, Yanagihara’s narrator sometimes sounds almost breathless at the horror and trauma that needs to be described. There are lengthy, gruesome depictions of the unending abuse Jude suffered as a child, but it is Jude’s responses to the trauma that become singularly affecting, even more so than the abuse itself. Yanagihara conveys such beauty and pain through her language and metonymic use of certain gestures, moments, and belongings. I have never cried more than I did while reading this text.

The thing about trauma is that it leaves an imprint that cannot be erased, becoming a rupture or absence in one’s psyche whose logic is irreversible. Yanagihara manages to give words and life to this trauma on the page, and is able to convey very clearly some of the ways it imprints on an individual. When Jude starts dating an apparently benevolent older gentleman who turns out to be another monster, for instance, the narrative proves the old psychoanalytic dictum that what doesn’t get resolved gets repeated.

At times, Jude comes across as almost superhuman in his innocence, generosity, and benevolence. He has self-mastered almost every single cooking skill, and his success as a lawyer is sometimes too briefly explained. Yet his character also rings incredibly true as a traumatized individual, and some of the ways in which he articulates (or doesn’t articulate) his pain and grief are particularly devastating to witness.

To call this “The Great Gay Novel,” as many reviewers have done, seems to be a disservice to its brilliance. The term “gay” only appears a couple times in the entire text, and usually in reference to a media intrusion that wants to force this label onto a character. Sexuality does not define any of these characters’ lived realities. People sleep with different people, and Yanagihara is careful not to label these intimacies but to let them exist simply as intimacies without bludgeoning them into some kind of imposed external rubric.

This is a novel in which both successes and failures are rendered larger than life, and yet the intimacy between the four men sustains this larger vision in ways that feel real and authentic. Yanagihara proves that perhaps no one can write better about intimacy between men than women: it is the friendship between these four men that is at the heart of this novel. These friendships form the connective tissue that sustains Jude to become who he becomes, that allow him, in the words of the title, to live a little life. A Little Life is a truly devastating read, in the way only truly great novels can be.

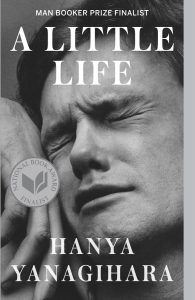

Hanya Yanagihara, A Little Life, (Anchor Books, 2015), Paperback, 816pp., $22.00.

Asam Ahmad is a poor, working-class writer, poet, and community organizer. His writing tackles issues of power, race, queerness, masculinity, and trauma. His writing and poetry have appeared in CounterPunch, Black Girl Dangerous, Briarpatch, Youngist, and Colorlines. His poem “Remembering How to Grieve” can be found in Killing Trayvons: An Anthology of American Violence.