by Geer Austin

When I agreed to lead a creative writing workshop for homeless LGBT youth, I had been leading workshops for about ten years. The earliest ones had taken place in the apartment in the Park Slope section of Brooklyn where I lived with my domestic partner. Those groups consisted of people like me, middle class urbanites with time and money to spare. Since then, I’d led a group of low-income and formerly homeless adults, persons with serious mental illness, and persons living with HIV/AIDS in a supportive housing residence in Times Square, but homeless youth promised to be even more vulnerable and challenging than them.

I felt as if a PhD in clinical psychology would be good training for communicating with the members of my new workshop, but I was armed only with a B.A. in literature from Bard College and a certificate in leading workshops from Amherst Writers and Artists, a not-for-profit organization based in Amherst, Massachusetts. Pat Schneider, the founder of AWA, believes writing is an art form that belongs to everyone, and her organization has trained leaders who founded workshops, for underserved as well as mainstream populations, across the U.S. and Canada, as well as in Ireland, Japan, Singapore, Malawi, the Netherlands and India.

The first time I entered Sylvia’s Place, an emergency night shelter for homeless LGBT youth, where my new workshop started out (it later moved to New Alternatives for LGBT Homeless Youth), I ran into an enormous young woman I’ll call Ronnie. She informed me in a loud voice that I could not lead the workshop on the third floor – in the offices of the Metropolitan Community Church, the sponsor of Sylvia’s Place – because she refused to climb the stairs.

Okay, I mumbled, caving into the first of many demands from workshop participants. I hesitate to call them students because AWA had trained me to be a leader rather than a teacher, and Pat Schneider had drilled one of her core beliefs into my head, “a writer is someone who writes.” In other words, the workshop leader is a writer among other writers. A facilitator. So my encounter with Ronnie was a meeting of two writers.

Ronnie would tell me over the course of our three year acquaintance that I was clueless, that all of my writing prompts were uninspiring, but also that she came to Sylvia’s Place mostly because of me, and that mine was the first workshop she’d ever attended and she’d since become a devoted workshopper. By then she had published some of her pieces, some with my assistance and others on her own.

Sylvia’s Place was named after Sylvia Rivera, a transgender heroine of the Stonewall rebellion, and it attracted a number of transgender youth. Many of them, as well as some of the other boys and girls, worked in the sex trades. For the transgender girls, sex work was one of the few opportunities available to them, as most employers shunned them. Many of the youth abused drugs and/or alcohol, and there were absences for sojourns in Riker’s Island, a prison complex located in the East River between Manhattan and the Bronx. But also, some left the shelter system for their freshman year at college, mostly due to the efforts of Kate Barnhart, a tireless advocate who worked at Sylvia’s Place before founding New Alternatives for Homeless LGBT Youth, and others passed high school equivalency exams and were placed by Kate in jobs and apartments of their own.

So what happened in my workshop? When the youth and I sat around a table in the shelter, we were all intent on writing (though chaos swirled around us as dozens of other youth dropped in for dinner, conversation and dancing). I followed the guidelines taught to me at AWA, provided a prompt and instructed the youth to use it as inspiration or to write about anything else that popped into their minds. Following a short writing period, I asked if they wanted to read what they had written. And after each reading, we commented on the piece using these parameters: we assumed that all writing was fiction, we spoke about “the narrator” rather “you” and we made only positive comments. For example, we’d say, “I liked when the narrator rescued the baby.” We never said, “Why did your mother neglect that baby? She oughta be thrown in jail!” These rules were invaluable at Sylvia’s Place where feelings were easily hurt, arguments could escalate into fistfights, and the staff told war stories about mopping blood off the floors.

And what did the youth write? They wrote about mothers abandoning their children, and grandmothers picking up the slack. About voyages into outer space. About vampires and superheroes and gods and goddesses. About sex! About parents who kicked their children out of their homes when the kids came out to them. About growing up in foster care. About running away. About transitioning. About fathers and stepfathers who raped boys and girls. About hunger. About cold. About love. They told some of the rawest and most compelling stories I have ever heard.

On my first day at Sylvia’s Place, I couldn’t foresee the stories I would hear or how leading the workshop would change me. After my dialogue with Ronnie, all of us writers took our places at a big table, and I passed out pens and notebooks and explained the workshop rules. I looked around the table and saw experimental hairstyles matched by radical outfits culled from stacks of donated clothing. I was wearing the suit and tie required by my day job (the huge chunk of my life not devoted to poetry).

A transgender girl looked me in the eyes and said, “How do you identify?”

I hesitated for a moment. No one had ever asked me that question. Then I said, “I am a gay man.”

“I thought so,” she said, but I don’t like to make assumptions.

She stared or maybe glared at me, and I had one of those lightning bolt moments. A combination of shame and revelation. Assumptions, I thought. Those are bad things. I’d made assumptions about these young people before meeting them. I needed to open my mind and take them in.

A couple of years later, a boy wrote a piece that included the words “my homeless wisdom.” I commented on the phrase, and everyone else at the table nodded their heads, as if to say, yeah we all have that. I studied their faces, each of them young, some missing teeth, some scarred, others breathtaking in their perfection. And I had another epiphany. I had been taking care of them by showing up every week, bringing them snacks, listening to and commenting on their creative writing, but they had also been taking care of me. All of them had been through harder times than I could imagine. And they were wiser than I was in many ways, though they were also impulsive, sometimes rash, young people. Layers of experience had molded their personalities, but these layers had been piled on rapidly at a young age. I suddenly knew that they had been going easy on me, treating me as if I were a sensitive child. Because I was the outlander, the one who hadn’t yet graduated from the University of the Streets. Leading the group had been my postgraduate education in tolerance and self-awareness. I hadn’t needed a PhD in clinical psychology to deal with homeless LGBT youth. I had only needed to learn to listen.

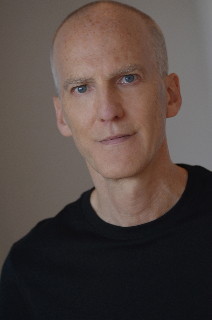

GEER AUSTIN’s poetry and fiction has appeared in MiPOesias, This Literary Magazine, Potomac Review, Big Bridge, Mary: a Literary Quarterly, and Ganymede Unfinished, among others. He is the former editor of NYB, a New York/Berlin arts magazine. He lives in New York.