Reviewed by Asam Ahmad

In Nick Comilla’s Candyass, a novel that stops tasting sweet about halfway through, an adolescent punk kid from a small town in Pennsylvania narrates his sexual coming of age and various experiences with gay life in Montreal and New York City. Purporting to be a novel that reveals new facets of gay sex and gay life, Candyass inadvertently lays bare the all-consuming narcissism at the heart of so much white gay male culture today.

Arthur, in Montreal for university from the States, considers himself a poet (before he is one) and is committed to living life seeking out muses in every boy he fucks. In this mess of sex, Arthur falls head-over-heels in love with Jeremy, a younger boy from the suburbs of Montreal.

Arthur has a tendency to speak in grand, generalizing terms without showing any signs of being aware that he is making grand, generalizing statements. He often thinks he is being profound when he is really just sharing common-sense gay wisdom: “We smoked cigarettes and started to have real conversations. This was typical of guys my age: it was always easier for us to actually talk after the sex.” He notes that “people tend to talk a lot of shit about the gay village […] Apparently, being free is boring. They want a return to secrecy, to feeling deviant, to a past we can’t experience.” While it’s true that some queers today nostalgically yearn for the days of underground cruising, this statement erases any other reason—gentrification, racism, sexism, transphobia, etc.—people may have for not liking the gay village and makes it seem like the village is nothing other than a utopian vision of freedom, liberty, and égalité.

Arthur is a skinny, smooth, good-looking white twink who calls his desire “picky,” but cruel would be more appropriate. When he first hooks up with Jeremy, he almost changes his mind because Jeremy shows up with a little acne on his face and hair sticking up from the cold. Arthur’s experiences of gay life are coloured by what he looks like, but he rarely seems to be aware that different people with different bodies might have different experiences with gay life and gay sex than he does. For him, we all “get so high we forget it wears off. The clothes are tight to our skin like tattoos, but they slip off effortlessly. Our wrists have been stamped so many times, there’s a shadow on the skin.” Clearly, this “we” only includes certain kinds of gays, but Arthur has no qualms speaking as if he is speaking for the entire gay community. Like many white gay men, Arthur presumes that his singular experience of marginalization makes him an expert on the lives of everyone around him.

The narrator spends most of the time pondering why Jeremy won’t settle down with him even though they are clearly in love, but Arthur has no self-awareness of his own narcissism to make the pondering meaningful or profound in any way. He cannot see that his desire to seek poetry in other men is an incredibly selfish and narcissistic mode of attempting intimacy with other people. When he moves to New York City and comes back to visit Jeremy, he thinks, “this thing between me and Jeremy, whatever it is, has faded. We’re not in sync when we talk to each other anymore. Jason was right: I left, I advanced. […] I’ve watched too many of my muses die.” This is perhaps the only man Arthur has ever loved, and in this moment, he is nothing more to him than a failed muse. Near the end of the novel, after his abusive and mentally ill boyfriend overdoses on cocaine, Arthur wonders, “Why can’t I find a muse who doesn’t fucking destroy me?” It’s hard to resist the urge to slap him in the face and yell SNAP THE FUCK O UT OF IT.

UT OF IT.

The entire novel is punctuated with lines of poetry, and most of the time, these poems feel either inconsequential or incomplete. It’s hard not to wince at lines like “I lube my stroke and all the dudes glide glad / I trick my treats and all is kink S/M / I stub my smoke and the skin sizzles sad.”

Reading this novel, one feels that whole chunks of narrative are absent or missing: we are parked inside the head of a man with an incredibly narrow and limited point of view, who does not seem to be aware that he is offering us an incredibly narrow and limited point of view. When his roommates in Montreal ask him to move out because he does not contribute to the “communal feel of the household,” one can’t help but sympathize with them.

It would be one thing to script this prevalent white gay cultural voice in order to do something with it—problematize it, mock it, parody it, historicize it, etc. Instead, all we get is the voice itself, as if it is communicating something real and authentic rather than being the fantasy that white gay male culture has immersed itself in.

There is nothing new or radical in the vision Candyass offers us, despite the narrator’s many proclamations otherwise.

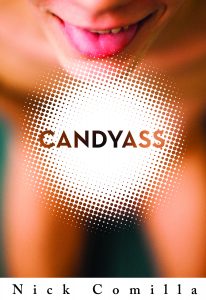

Nick Comilla, Candyass. (Arsenal Pulp Press, 2016), paperback, 158pp., $15.95

Asam Ahmad is a poor, working-class writer, poet, and community organizer. His writing tackles issues of power, race, queerness, masculinity, and trauma. His writing and poetry have appeared in CounterPunch, Black Girl Dangerous, Briarpatch, Youngist, and Colorlines. His poem “Remembering How to Grieve” can be found in Killing Trayvons: An Anthology of American Violence.