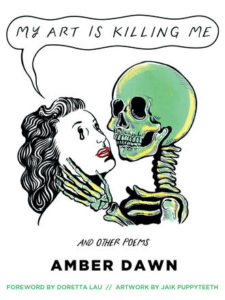

Amber Dawn, My Art Is Killing Me and Other Poems (Arsenal Pulp Press, 2020), 128 pp., $17.95.

My Art Is Killing Me is a poetry collection that feels like a wound. Amber Dawn’s latest collection of mostly free verse poetry from Arsenal Pulp Press weaves her lines with issues both personal and political, and refuses to separate them out. Whether it’s her own experience with sex work and family trauma or university staff asking for free emotional labour alongside trolls harassing her online, Dawn’s poems in this collection (along with the stunning art that accompanies the poems by Jaik Puppyteeth) are twisted up with feelings of betrayal, anger, and the psychic and physical trauma that comes with wounding.

There were two main things that I realized while reading My Art Is Killing Me. One is that, in spite of my love for Amber Dawn, this collection did not target me as an ideal reader, but someone who’s just discovering these outrages, both personal and systemic. The second thing I realized is that while her art is killing her, Amber Dawn knows it is not a fatal wound—yet. The title is important because the word “Killing” is in the –ing form of the verb (gerund); this death is not yet happening, but if nothing is done about these issues, then she—and many like her—will not survive. That is where, once again, the ideal reader steps in and takes up the mantle of hope, strife, and survivorship. These poems are for them: that person still in pain and desperate to make sense of their pain, and these works are meant to be spoken aloud.

As I said before, Dawn speaks about heavy emotional and intellectual topics like the systemic issues involved in sexual harassment in academia, recovery from sexual abuse, and the ways in which the internet has changed our communication to seem more like abuse. Indeed, many of these poems feel as if they will require a crash course in Gender Studies, LGBTQ History, and Cultural Theory in order to understand the nuance and depth to her arguments rendered through sparse poetic lines. In her poem about Hollywood and sex work, “Hollywood Ending,” Dawn begins the poem with the line: “Filmdom vanity, ersatz divinities. By the year 2015, twenty five actresses / had received Academy Award nominations for playing sex workers onscreen” (29). The poem continues to list off the actresses and their roles, the media’s responses to them, and how these roles do not match up to the real life of sex workers, and what this means culturally. The poem is long—many of the poems in this collection span at least three pages—but this one is especially ambitious as it flits between news events with the language of a report, then the ornate diction of a Gender Studies professor as Dawn tears these news stories apart for their latent misogyny and “slut scapegoating” (31).

Other poems also use a mix of real-life reporting alongside the narrator’s artistic views. This is done for strategic reversal of power, such as “Tragic Interview,” when Dawn writes out the numerous questions her narrator has been asked while participating in academic or media interviews as a sex worker. Instead of being forced to answer, her poem turns the question back on the questioner, and leaves them in silence to fill in the blanks. Another poem, “How Hard Feels,” does much the same with its haunting lines left for the audience to complete and repeat for themselves. This poem discusses sexual harassment from an advisor in the speaker’s MFA’s program, linking it to other examples of historical abuse; the poem moves from the specific instance of abuse the narrator experiences to the outside world where abuse continually happens, connecting these experiences through the repeated line: “everywhere there is a man.” While Dawn or her narrator names no names, it is quite clear who these men are if you’ve looked online or in the news cycle lately.

I highly respect Dawn’s ability to turn political issues into poems, and then to survive all the other injustices she outlines in this collection. I also respect Dawn’s credentials, as she has written across multiple genres (from memoir to fantasy fiction) and has an ability to dynamically change her poetic voice. The poems in this collection are far different than the calming glosas in Where The Words Ends and My Body Begins and they are certainly different from her usual fairy tale and mythic images she weaves in her poetry for Hustling Verse (though she does revisit beloved images of witches and mermaids in several poems, like “An Apple, or Haunted,” “Fountainhead” and “Stregheria Instructional #1”; they are shorter works, however, and seem overshadowed by the real-life issues that bleed through this collection otherwise).

So when I follow this praise by saying that My Art Is Killing Me is not my favourite Amber Dawn work, I am not saying this in a dismissive way. This collection is quite good, and necessary in so many ways, but it was not what I was expecting at first.

To convey a sense of My Art Is Killing Me, it’s useful to trace the lineage between this work and Sub Rosa (2010), Amber Dawn’s fantasy novel about a group of magical sex workers. To me, that work manages to confront the gritty reality of a maligned and minority position (in this case, sex worker and abuse survivor) and turns that experience into something both realistic and magical. These ideas seem contradictory—how can something realistically horrible be so wonderfully magical at the same time—but this contradictory sensation (some call it cognitive dissonance) is the core of the nature of trauma. My experience of trauma is different than Dawn’s, but I relate to her as a survivor in some way and see my own complicated feelings replicated in her work. I suspect many of her readers do as well.

As I read these poems in 2020, though, I became aware of an increasing sensation of rootedness to the ground, as if the poetry was holding me in place and not letting me go. I wondered if this could be the effect the author had in mind. As much as I loved some of the poems in My Art Is Killing Me, I found myself craving the same sense of triumph in the darkness that awaits readers in Sub Rosa. I couldn’t stare any longer at wounds. I do not want to deny my personal traumas, nor Dawn’s, nor the historical ones which we are currently living through, but I am not the target audience anymore. These poems could be a revelation to someone who is just starting to find language for their wounds, and confronting Dawn’s precision in her own wounding could be the exact thing they need to read.

My Art Is Killing Me is a work written for those who are at the beginning self-healing work and just now discovering the personal and political nuances of their trauma. The ideal reader still needs to be angry, outraged, and to refuse to let the wound heal because they now understand that their trauma is about more than just their experience; that trauma is cultural, it’s historical, it’s generational. The ideal reader needs to sit with Dawn’s words and let them open that wound in order to heal it.

Eve Morton is a writer living in Ontario, Canada. She teaches university and college classes on media studies, academic writing, and genre literature, among other topics. Her collection of poetry called Karma Machine will be released in 2020. Find more info on authormorton.wordpress.com.

Eve Morton is a writer living in Ontario, Canada. She teaches university and college classes on media studies, academic writing, and genre literature, among other topics. Her collection of poetry called Karma Machine will be released in 2020. Find more info on authormorton.wordpress.com.