Reviewed by Asam Ahmad

If all poets hope to occasionally make the ineffable speak, Ocean Vuong does so effortlessly in almost every poem from his new collection of poetry, Night Sky with Exit Wounds. It’s hard not to become undone reading many of these poems, and you may find that something inexplicable has shifted within you when you put the book down.

Vuong has a unique ability to create poetry out of seemingly disparate themes: love, war, intimacy, sex, family. Another way to say this might be: his poetry is a reminder that there is nothing disparate about any of these themes, that there is a confoundingly straight line from war to family to sex to intimacy to love. “There are / men who touch breasts / as they would / the tops of skulls,” “the best way to understand a man is with your teeth,” and “a man in climax [is] the closest thing to surrender.”

Vuong’s biographical history bears heavily on a lot of these poems. In “Aubade with Burning City,” the poet intermingles lines from Irving Berlin’s White Christmas with a terrifying poetic rendition of the April 1975 bombing of Saigon by US troops. The juxtaposition is jarring to say the least, but also historically apt: a note tells us the song was broadcast on Armed Forces Radio as the final bombing and evacuation were under way. Reading the poem reminds one of the particular ways in which formerly colonized people and those in the diaspora carry violence and heartache with them, and the ways in which trauma gets written on our very bodies. In another poem, the speaker notes “the grandfather fucking / the pregnant farmgirl in the back of his army jeep.” Vuong’s grandfather was a US serviceman who married his grandmother, a rural farm girl. “[N]o bombs = no family = no me.”

“When they ask you

where you’re from,

tell them your name

was fleshed from the toothless mouth

of a war-woman.”

Maybe this is why reading Vuong’s poetry makes palpable the fear that loving someone is as dangerous as venturing onto a battlefield. It’s clichéd to compare love with a war zone, but Vuong nuances this trope by never letting us forget the long history of colonialism and imperialism that is always bearing down on how queer people of colour must contend with life and loving in the diaspora. As someone who is already living an inheritance of violence, Vuong makes us feel loss in ways where it isn’t clear if it is war or love that is the topic. “I am running / toward a rusted horizon, running / out of a country / to run out of.”

These poems are harrowing, but the precision and beauty of the poetry itself makes some kind of hope feel palpable. “Seventh Circle of Hell” begins with a note from the Dallas Voice in the top right corner: “On April 27, 2011, a gay couple, Michael Humphrey and Clayton Capshaw, was murdered by immolation in their home in Dallas, Texas.” The poem itself is written entirely in the footnotes: they are numbered haphazardly on the page, so one feels as if one is reading a zigzag or puzzle that never quite fits or comes together.

As if my finger, / tracing your collarbone / behind closed doors, / was enough / to erase myself. To forget / we built this house knowing / it won’t last. How / does anyone stop / regret / without cutting / off his hands?

[…] Just tell me the story / again, / of the sparrows who flew from falling Rome, / their blazed wings. / How ruin nested inside each thimbled throat / & made it sing

It sometimes feels like this poet is willing to dig in sacred, violent places to gift us with a different kind of knowing, to allow us to imagine a different way of being in this world.

The speaker of these poems invariably describes his father in the most intimate and the most violent terms. The epigraph, appearing in both English and Vietnamese, gives us a clue for how to read this text. It reads: “for my mother [& father]”—“&” signalling that the declaration to his father is almost an afterthought, a necessary formality rather than a real desire, the brackets reminding us that the place of the father—whether biographically or psychologically—is being interrogated and put under pressure in these poems.

“Do you know who I am, ba?” The answer never comes: “The answer / is the bullet hole in his back, brimming / with seawater.” At another point, the speaker addresses himself: “Ocean, don’t be afraid. / […] Your father is only your father / until one of you forgets. / […] Ocean, / are you listening? The most beautiful part / of your body is wherever / your mother’s shadow falls.”

Vuong has a keen eye for visual imagery: there are cathedrals in sea-black eyes, a black piano in a moonlit field, bones turning into sonatas, and even “the trees know the weight of history.” Vuong’s ability to hear the cadences of the English language and the tensile precision with which he creates wholly unanticipated linguistic resonances leave the reader feeling invariably shaken, understood, seen, and at times breathless.

It’s hard not to reach for such effusive adjectives when describing the experience of reading Vuong. It’s better to simply tell everyone in your life to go out and read these poems.

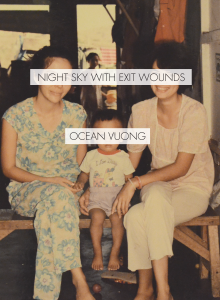

Ocean Vuong, Night Sky with Exit Wounds (Copper Canyon Press, 2016), Paperback, 92pp, $16.

Asam Ahmad is a poor, working-class writer, poet, and community organizer. His writing tackles issues of power, race, queerness, masculinity and trauma. His writing and poetry have appeared in CounterPunch, Black Girl Dangerous, Briarpatch, Youngist, and Colorlines. His poem “Remembering How to Grieve” can be found in Killing Trayvons: An Anthology of American Violence.