Interview by Emma Rhodes

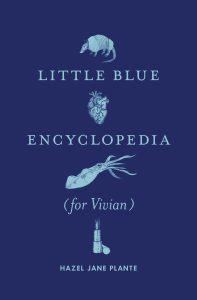

Hazel Jane Plante’s playful and poignant novel Little Blue Encyclopedia (for Vivian) sifts through a queer trans woman’s unrequited love for her straight trans friend who died. A queer love letter steeped in desire, grief, and delight, the story is interspersed with encyclopedia entries about a fictional TV show set on an isolated island. The experimental form functions at once as a manual for how pop culture can help soothe and mend us and as an exploration of oft-overlooked sources of pleasure, including karaoke, birding, and butt toys. Ultimately, Little Blue Encyclopedia (for Vivian) reveals with glorious detail and emotional nuance the woman the narrator loved, why she loved her, and the depths of what she has lost.

Hazel Jane Plante is a queer trans librarian, cat photographer, and writer. Little Blue Encyclopedia (for Vivian) is her debut novel. She currently lives In Vancouver on the unceded territories of the xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam), Sḵwx̱wú7mesh (Squamish), and sə̓lílwətaʔɬ (Tsleil-Waututh) Nations.

How much of Little Blue Encyclopedia (for Vivian) is true and how much is fiction?

How much of Little Blue Encyclopedia (for Vivian) is true and how much is fiction?

That’s a tricky question. I can honestly say that it’s all fiction, but some of it is true. It’s kinda like what Emily Dickinson wrote: “Tell all the truth but tell it slant—”. Or maybe like the Pavement album title (supplied by one of my favourite writers, David Berman), Slanted and Enchanted. There’s plenty of truth in the novel, but it’s been slanted, enchanted, laundered, and refracted.

Do you think discussing real grief, love, and desire is somehow easier when pillowed by fiction? How does fictionalization or experimental writing function in your novel—what’s the purpose or effect of this style of writing?

It might be easier to write about grief, love, and desire through fiction. It does make you feel somewhat less vulnerable and might give you a degree of distance.

I love playing with form, and I love it when a work’s form is deeply connected to its content. It’s kinda like how Jean-Luc Godard said he saw style and content as being “like the outside and inside of the human body—both go together, they can’t be separated.” One of the challenges is to write something that is intrinsically and organically tangled with its form. I’ve gotten better at this over the years, but it’s an ongoing challenge. Writing a novel in the form of an encyclopedia about a fictional TV show seemed like a thorny, fascinating challenge. But, it took nine years to finish this book. One of the reasons that I like constraint-based writing is that it troubles the process and gets you to think differently and leads you to places you’d never go to otherwise.

Although Little Blue is a fictional television show, is it based on anything? What gave you the idea to create this fictional show that frames the novel?

There are a lot of TV shows that influenced the fictional series Little Blue. Mostly, I was inspired by weird shows with an array of eccentric characters set in distinctive fictional locations. A few shows that fit that bill would be Twin Peaks, Northern Exposure, Lost, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, and Gilmore Girls.

At first, I tried to write a book about a fictional TV series that was similar to the kinds of slender books that BFI publishes about classic and cult films, as well as the 33 ⅓ series of books about albums. I wanted to suggest the contours of the show, its main characters, plot points, its actors, its creation process, its critical reception, etc. But the show would only exist between the folds of my book—and in the minds of readers. At some point, I folded that idea into another project that I was working on about a relationship between two trans women. Peanut butter, meet jelly.

Viv claims that “art that tried to capture life through realism always fell short” (6), do you think this is true in writing? Does this fall in line with the experimental structure of Little Blue Encyclopedia (for Vivian)?

I think it’s more true for me with visual art than with writing. I’m drawn mostly to visual art that distorts and contorts, rather than “realistic” art. I like some writing that fucks with the canvas, but I also like writing that crystallizes the world around me by fitting words to things and feelings that help illuminate them.

There’s some realism in my novel, but I also enjoy fucking with the frame. It’s realism via pointillism with pop art thrown in, maybe.

What television channel would Little Blue be on? Would it be available on Netflix? Under what genre—drama?

Hmm. Good question. Little Blue originally aired on the short-lived (fictional) cable network Fine Media. It wouldn’t be available on Netflix. If it were available on any streaming network, I’d hope it would be part of the Criterion Channel with bonus materials, like commentary tracks and a feature-length documentary. I’m not sure about the genre. Drama is a pretty capacious genre, so that might work, but some of it is pretty odd and off in ways that lean towards comedy. Back in the 80s/90s, some people tried using the term “dramedy” to describe these kind of shows, but “dramedy” is a puke-emoji-worthy word.

Is there something about art that is more attractive to marginalized people, like those in the LGBTQIA+ community? Do you think it has to do with a lack of freedom to express oneself that other forms of expression become so attractive?

I’m not sure if marginalized folks are more drawn to art. I think art is profoundly important for lots of people. I do think that seeing ourselves reflected in art is vital. One of the main reasons that I was scared to transition is that trans characters I saw in films and TV suggested that my life as a trans woman would be shitty. (There have been some great trans characters in recent years on shows like Pose and Sense8, but I still see transphobic shit way too often.)

Do people become better artists when they suffer? Is there something in grief, loss, and loneliness that lends itself to imagination and reflection? Does art and writing make dealing with loss easier somehow, cathartic?

No, people do not become better artists when they suffer. I vehemently disagree with this idea. It’s just not true. I spent many years of my life in a thick fog of depression and anxiety. It took me about a decade of really fucking hard work and many touch-and-go day/nights/weeks/months to tunnel my way through and feel relatively okay in the world. When I felt like a jangling husk of nerves, I was not creating much art. I was just trying to keep myself alive.

At times, grief, loss, and loneliness might lend themselves to imagination and reflection, but while feeling the full weight of those emotions I don’t think most of us can be at our creative best.

I’m not sure that art and writing make dealing with loss easier. They might for some of us. I’m reminded of something I read years ago that Harry Crews said about how he thought it would be therapeutic to write about his traumatic upbringing (in the sharp, but harrowing memoir A Childhood: The Biography of a Place), but he found that writing it unearthed such painful memories that he went on a years-long bender. Personally, I find that being absorbed in art (rather than creating it) can help at times.

Did you find it odd or difficult to write about your own writing process, about this project and the people who helped you through or influenced the project? Is it uncomfortable meta-writing like that, or did it feel natural and like it worked?

I wrote about the fictionalized writing process of the narrator and how it was influenced by her fictional friends, so I didn’t find it odd or difficult. (My writing process for this book was completely different from the narrator’s process.) I’m pretty comfy with meta-writing, or, in this case, pseudo-meta-writing.

Is there a reason the four images are the ones on the cover? Why was the armadillo and squid picked over the middle finger and ghost, or is it arbitrary?

First of all, I love so much that my book has 26 alphabetical illustrations. The illustrator is Onjana Yawnghwe, who is an amazing poet and one of my best friends. As for the four illustrations that appear on the cover, you’d have to ask Kevin Yuen Kit Lo at LOKI in Montreal, who designed the cover. He was given an early draft of the novel, along with Onjana’s illustrations. I think he made some great choices that draw people in. I also sent Kevin my thoughts on the kind of cover that I wanted and stressed that I wanted something “simple and evocative.” Oh, I also said that I didn’t want a blue cover because I thought it was too on-the-nose. Obviously, I was wrong. The book’s cover is two shades of blue and I love it so much.

I definitely don’t think the images are arbitrary, and I’ve had people suggest why they think the cover works so well (e.g., we have three natural objects in the armadillo, heart, and squid, with the final object being human-made; all four objects are tied to Vivian), but I haven’t talked to Kevin about it yet because they just felt right to me.

Emma Rhodes is a fourth-year student at St. Thomas University in Fredericton, NB. She is completing an honours in English Literature with a concentration in Creative Writing. She is an intern at both Goose Lane Editions and Moorehype Publicity, and her work has been published in The Aquinian, Sonder Midwest Magazine, and The New Brunswick Literary Encyclopedia.

Emma Rhodes is a fourth-year student at St. Thomas University in Fredericton, NB. She is completing an honours in English Literature with a concentration in Creative Writing. She is an intern at both Goose Lane Editions and Moorehype Publicity, and her work has been published in The Aquinian, Sonder Midwest Magazine, and The New Brunswick Literary Encyclopedia.