Perhaps it was because I had finished reading Between the World and Me by Ta-Nehisi Coates that I had already been thinking of bodies and how they moved in the world before starting Kai Cheng Thom’s a place called No Homeland. Her first poetry collection conjures the image of a person wandering, forever lost—but what I found between the pages of her resonant poetry and lucid prose was someone who knew exactly who they were, but who was robbed of the ability to tell their story because their body had been misread. Each poem then becomes a way for Thom to narrate the gap between her Chinese transfeminine body and the outside world, an act that saves her life over and over again.

Most transgender narratives attempt to bridge the same gap, but while most mainstream depictions do this by forgetting the body exists (since the trans person is “trapped in the wrong body”), Thom calls the body into direct focus. Even in poems where she seems to invoke the typical “trapped” trope that comes along with transgender storytelling, like in “there is a poem,” she subverts it by focusing on the physicality of the throat, and by doing so manages to avoid a universalizing view of trans identity.

Sometimes Thom evokes the body through the abject (blood is a recurring theme in this work, especially blood from sexual violence in “trauma is not sacred”), sometimes it’s through injury (as in “when you die”), and sometimes it’s through sex (as in “3 love stories”). Even Thom’s depictions of food conjure the viscera, since it’s through the act of eating that we all gather around a table and become physically present both in our own bodies (through hunger/fullness) and in our families. Her poem about learning to chop from her mother and then losing her mother ties both of these ideas together through the image of a severed finger. Thom writes, “you don’t get back what you cut off […] I will be chopping vegetables when you die, nonchalant.” The family line exerts pressure on the child, especially the transgender child, when parents demand certain behaviours—but parents are also part of the child and wish the child to be safe from bodily harm, which in this poem causes its own type of bodily harm. The chopping scene sticks with me long after reading because it conjures up surgery, trans identity, and family expectations of gender and safety so strongly; the fact that Thom does this through her evocative language alone is extraordinary.

In many ways, it is the body, not the universal “I,” who is the speaker in all of her poems. Thom’s poems are largely built off oral tradition, making them authorless and memorable; the singsong-like structure and repeated choruses of “diaspora babies” and “stealing fire” evoke a melody on the page. It’s the body, and its tie to a large cultural history, that doesn’t forget and allows the poet to say what can’t be expressed. This includes the stories from Thom’s grandmother, but also the trauma of colonialism and intergenerational trauma that “the river” documents in sprawling poetic detail.

Pleasure and pain become intermingled in this work, but not in a way that is worn out. When Thom writes about how violence and love share the same letters, I put the book down because I’d never noticed how intertwined those words were; perhaps that demonstrates my own privilege when it comes to this specific type of sexual violence that intersects with race. But this is what Thom does so well in her poems: she draws attention to the lines of privilege, to intersecting oppressions and identities, by naming the body. Once the power structure has been given a name, it becomes visible, and the reader can draw their own conclusions.

That being said, some poems are direct callouts—such as “dear white gay men,” but this particular poem is delivered in such a stark manner that its honesty is refreshing and funny. By virtue of naming race in this poem, she’s named that power structure and directed blame at a group who often forgets their body, and the whiteness and power that go along with it. Similarly, her poem “the wounded for healing” acts as a callout, but in a more sympathetic way. There were entire sections of this poem that I wanted to get framed—to make her words physical beyond the page—because I’d internalized its meaning, perhaps in a way similar to how Thom describes her own “book fetish” in her poem about Amber Dawn. Poetry does have the ability to change things—but it must be conscious of that power in order to change them.

My favourite poem is one of the most hopeful ones. In “the lady in the moon” Thom describes her speaker lying back on the grass during sex, but then orients her poetic vision towards the moon and recalls the myth of the woman who used to live there. This woman is a goddess who can turn “mortal flesh / into the divine”; by the end of the poem, Thom transforms her speaker into that divine moon, making her body take on a new landscape without shame. To me, it’s the most hopeful poem in the collection because it focuses on a future where the borders we assign to bodies disappear—but it doesn’t do this through a utopian vision that forgets its origin. It roots itself, literally to the grass on the ground, and becomes a tangible manifestation of a possible future.

Kai Cheng Thom’s work is magical, marvellous, and bodily. It’s something I won’t forget for a long time.

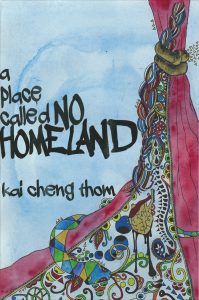

Kai Cheng Thom, a place called No Homeland (Arsenal Pulp Press, 2017). Paperback, 85pp. $14.95 CAD.

Evelyn Deshane has appeared in Guts magazine, Briarpatch magazine, and Bitch magazine. Evelyn (pronounced Eve-a-lyn) received an MA from Trent University and is currently completing a PhD at University of Waterloo. Their most recent project #Trans is an edited collection about transgender and nonbinary identity online. Visit evedeshane.wordpress.com for more.

Kai Cheng Thom will be reading at both Glad Day Bookshop and Another Story Bookshop in Toronto on Saturday, April 22nd during a launch crawl with Catherine Hernandez, author of Scarborough.