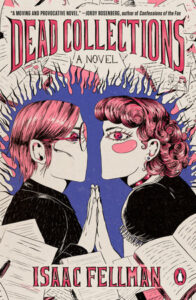

Isaac Fellman, Dead Collections (Penguin Random House, 2022), 256 pp., $17 US.

If Dead Collections was a space, it would be an archive, or perhaps a human heart: rich, moody, and funny, built with infinite care. This literary supernatural novel takes on the carefully interleaved lives and afterlives of objects, bodies, relationships, and identities with a skill that’s delightful to be around—and a wry sense of humour all its own. The result is a sexy, smart, terribly tender trans love story twined with Lambda winner Isaac Fellman’s perceptive take on the detritus we leave around and inside us.

Sol Katz is a forty-something trans archivist—and a vampire. Turned into a vampire as a last-ditch cure for tetanus, he’s hidden his vampirism from everyone but HR, surviving on weekly blood transfusions in a body that’s still breathing mostly out of habit—and secretly living in his underground office at a Marin, California historical society to avoid the sun.

When his archive acquires the effects of cult TV writer Tracy Britton—the creator of a 1990s X-Files knockoff that is Sol’s most enduring fandom—he’s eager to peek behind the inscrutable shapeshifters and queer-coded relationships of the show that meant most to him. But with it comes Tracy’s still-grieving wife, lapsed fanfiction writer Elsie Maine—and a startling, shy intimacy that sends them head-over-heels for each other.

However, as a series of weird, ghostly incidents in the archives escalate—and he’s evicted from his office squat by a transphobic co-worker—Sol’s brought face to face with his body’s needs, Elsie’s own gender struggles, and all he hasn’t processed: community, identity, afterlives, and one very haunted collection.

The joy of Dead Collections is that—like an archive, like a heart—it’s marvellously bigger on the inside. It has a thousand things to say: about the way we map our identities, about vampire tropes, about how fandom power relationships leak into real lives, about the ways we mediate experiences through other people’s art and distance and medical procedures, about how little we know about each other—and how that’s maybe not all bad.

And it has an intricate, playful way to say them. Dead Collections offhandedly provides readers a map of its own structure as Sol organizes Tracy’s collection—”screenplays, show bibles, subject files—lots of those, I’m sorry to say—personal correspondence, business correspondence.”—and then straight-facedly follows that index to a tee, telling its story through those formats. It’s a rigorous, brilliant structural feat, a solid indexing joke, and still emotionally substantial, because it builds off the novel’s central axis: that seeing events and people in different ways can help you understand how complex they are, and how fundamentally whole.

It’s that belief in human wholeness that smooths these intellectual fireworks into a read that’s smooth, accessible, and comforting. Sol’s wholeness—and his developing eye for the ways other people hold universes of complexity—anchors Dead Collections. Even as he qualifies his impressions, self-corrects, footnotes to reassure us this isn’t the whole story—even as he’s just plain wrong sometimes, he navigates the delirious crumbling and rebirth of his sense of self with a rare, steady sincerity.

Fellman—an archivist himself at San Francisco’s GLBT Historical Society—stitches these elements together with a precise, immersive style and a poet’s understanding of repetition, scansion, wordplay, and rhyme. The tiniest details of Sol’s world are so intimate that his San Francisco brims with horror, bedazzlement, and wonder—even when he doesn’t go out much.

It’s writing you can feel on your skin: capable of spinning texture and immensity in one phrase, and brimming with little juxtapositions. Fellman’s sentences push-pull against themselves—”her face collapsing into a smile,” or “turned it quiet and sour and safe”—to build that rising hum of things being less binary and more nuanced than anyone might guess. It’s language soaked in the process-driven experience of transition.

Dead Collections does tackle that question head-on: Sol’s unglamorous, medicalized vampire life is riddled with the casual yet all-consuming mechanics of “passing”—faking migraines to avoid sunlight and soaking his hands in hot water to manage a lifelike handshake. All around him, people toy with their names and identities.

But more subtly, Dead Collections constantly and expertly blurs the lines between bodies and acted-upon objects—but in a way that makes them all remarkably bigger for it. Sol’s first impression of Elsie is almost an artifact catalogue—”[her] body was of denser stuff, and her face was matte and inexpressive”—and objects like an untuned convention-hall piano with “severed nerves and broken nose” are persistently alive. It’s another way of getting at a world where your papers and letters can serve as your ambassadorial ghost; one populated by infinitely complicated people, where nothing’s quite fit to its intended use and everything is—or isn’t—or could be—alive. And where things might have a hope of working out, if we can find ways to give each other that space to be complicated.

That conviction that we can hold identities and still grow within them is what makes Dead Collections such a comfortable read. For all the difficulties and fireworks it’s built on, it’s a wonderfully peaceful book: funny, quiet, philosophical, sexy, and immensely warm. Sol’s coming to terms with every one of his identities—archivist, trans man, vampire, fan—steps away from drawing lines around what one should be. “It’s not an old story yet,” Sol tells us in the opening pages, “and I am still figuring out what it means.” And that’s all right. There are many ways to read an archive.

…

Novelist, editor and critic Leah Bobet’s novels have won the Sunburst, Copper Cylinder, and Aurora Awards, been selected for the Ontario Library Association’s Best Bets program, and shortlisted for the Cybils and the Andre Norton Award. Her short fiction has appeared in multiple Year’s Best anthologies and has been taught in high school and university classrooms in Canada, Australia and the US; her poetry has been multiply shortlisted for the Rhysling and Aurora Awards. She lives in Toronto, where she builds civic engagement spaces and makes quantities of jam. Visit her at www.leahbobet.com.

Novelist, editor and critic Leah Bobet’s novels have won the Sunburst, Copper Cylinder, and Aurora Awards, been selected for the Ontario Library Association’s Best Bets program, and shortlisted for the Cybils and the Andre Norton Award. Her short fiction has appeared in multiple Year’s Best anthologies and has been taught in high school and university classrooms in Canada, Australia and the US; her poetry has been multiply shortlisted for the Rhysling and Aurora Awards. She lives in Toronto, where she builds civic engagement spaces and makes quantities of jam. Visit her at www.leahbobet.com.