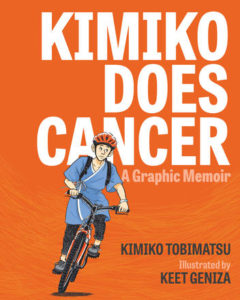

Kimiko Tobimatsu, illustrated by Keet Geniza, Kimiko Does Cancer (Arsenal Pulp Press, 2020), 96 pp., $19.95.

Kimiko Does Cancer, a graphic medicine memoir written by Kimiko Tobimatsu and illustrated by Keet Geniza, is a tender offering that critiques mainstream breast cancer narratives and the mythologies of strength. Tracing the relational impacts of illness through Geniza’s earthy green, grey and black ink hues and a wide array of subtle to expressive faces, this book is both a personal story about the experience of one young, queer, mixed race Japanese Canadian woman with cancer and a narrative about the expectations patients face from society, their families, communities and workplaces that limit their autonomy within the healthcare system. Giving readers a vivid glimpse of cancer as a deeply emotional, interior experience, Tobimatsu and Geniza create a non-linear story of recovery that is funny, lively, and full of honest self-reflection.

In a pandemic where more and more people are becoming disabled and contending with the long-term effects of illness, Kimiko Does Cancer is a gentle salve for weary grief. At the same time, in a scene where fellow cancer patients impose unrealistic optimism upon one terminal cancer patient, Tobimatsu reminds readers that “[l]eaving the room to grieve can be as important as maintaining hope” (42). Rejecting isolation for the solitude of grief is, in this case, a refusal of toxic positivity and cure culture. Illness and death are part of our lives, and yet we live in a world that largely runs on denial and disavowal.

Geniza satirizes this denial through cheeky illustrations of the beaming smiles of Macy, Stacy, and Lacy—three straight, cisgender white women who represent ideal patients according to dominant narratives about cancer. In one panel, these women hold hands as they sky dive, depicting cancer recovery as an Eat, Pray, Love adventure that allows you to “live in the moment” and gain enlightenment. Kimiko’s race, queer masculinity, and inability to “sweat the small stuff” make her feel out of place. At the same time, her identities make her an easy token as a research subject within the medical field—shown through the studies she is solicited to participate in–where the needs of younger queer people of colour are unrecognized and lesser known. In other words, the relief that Kimiko Does Cancer brings is a recognition that the white, cis-heteronormative, and traditionally feminine face of breast cancer is inaccurate and harmful. Having cancer does not necessarily turn patients into “survivors, fighters, [or] warriors.” With gentle humour, Tobimatsu questions the very notion of cancer as a war to fight. In choosing the graphic memoir form, Tobimatsu gives room for Geniza to show readers both the façades and real faces of cancer—the invalidating comments and conflicting advice from doctors, as well as patients’ internal struggle.

Just like the sudden arrival of illness itself, the book enters mid-conversation as Kimiko notices an abnormal bump on her breast while phoning her girlfriend. On the next page, readers dive deep into Kimiko’s internal monologue, with her thoughts racing through what feels like the narrowing doorway of her life—the person she will become, what she will look like, and what she will need to tell her friends. Geniza aptly illustrates a long stairway leading up to a closed door and in the adjacent panel shows Kimiko peeking out of one into the dimness of her home. This sense of confinement and the narrowing of perspective is contrasted with the overwhelm Kimiko feels later in her recovery. Here, she reflects that “[l]iving in the same area where I was diagnosed, radiated, harvested means cancer reminders are never far away… [t]he towering buildings trigger a pressure at the back of my eyes and throat. . . Sometimes I notice I’m holding my breath.” Geniza dramatizes this looming, suffocating pressure with large letters on buildings reading “YES. WE WILL DO EVERYTHING FOR THE CURE” and “WE WILL CONQUER CANCER IN OUR LIFETIME.” The wide-perspective of these panels visualize how such messaging is everywhere, even as Kimiko tries to ignore them. Kimiko’s experience was life-changing, but living beneath the shadow of cure is what ultimately diminishes and invisibilizes the effects of long-term chronic illness she experiences post-cancer.

Doors, as Geniza illustrates, are not only a narrowing of possibility, but also represent an overwhelm of different choices. Geniza shows Kimiko peering into one of six doors, each representing a different cancer treatment drug with no perfect combination of effectiveness and side effects, leaving her to wonder which door to pick. If the book is hopeful, it is in sharing how medical advances have improved the array of recovery options for breast cancer patients and in imagining what it means to centre the patients’ decision-making process, even if this process is daunting, scary, and never-ending. In the beginning of the book, Kimiko’s parents start to make healthcare decisions for her, but as she recovers, she learns to say no and seek out her emotional well-being on her own terms.

Tobimatsu dedicates the memoir “to our fellow sick queers.” The historical, political resonance here reminds readers of the queer folks who have passed on and survived the AIDS crisis, as well as disability justice movements in which queer folks are key leaders. It’s also a gentle call of recognition to a community whose needs and voices are routinely ignored. Taking cues from Black lesbian poet Audre Lorde and Black femme sex educator Ericka Hart, Tobimatsu’s work connects decades of sick queer writing with her own experience and the present moment. Tobimatsu and Geniza’s collaboration calls on us to connect cancer with disability, and understand disability justice as a movement that allows us to rethink how we relate to ourselves and the world.

Kimiko Does Cancer isn’t a loud, clanging story that clambers to break the silence about the queer cancer experience. It’s a quieter, more thoughtful reflection that walks readers alongside what it feels like to lose and regain autonomy as a sick person. Hers is a specific story of a human rights lawyer and queer person of colour who struggled with her lack of participation in protests, while daydreaming about redistributing official cancer research funds to migrant labour movements. It shows how hyper-focusing on work limited her capacity to stay present and take care of herself and how her menopause symptoms made it difficult for clients to take her seriously.

As shown through the range of expressions in Geniza’s illustrated faces and various panels depicting humorous interludes, this memoir skillfully balances the interplay between pleasure and critique. While Kimiko is critical of official cancer messaging and is no longer able to be as easygoing, she nonetheless lets herself enjoy the piecemeal “perks” of being a young cancer patient who receives “special treatment.” She yearns to belong to social worlds that are no longer accessible—“I know making time for myself is healthy… but it doesn’t stop the fear of missing out”—yet is still able to appreciate the brief moments of pleasure between pain: “The brief moment in a shower when the heat soaks into my bones, before it triggers a hot flash. / The sensory comfort of eating, something that is even more important now. / The few hours after waking up from a good night’s sleep, before I get tired again.”

Disability justice organizer and writer Mia Mingus describes access intimacy as “that elusive, hard to describe feeling when someone else ‘gets’ your access needs. The kind of eerie comfort that your disabled self feels with someone on a purely access level.” Throughout Kimiko Does Cancer, Kimiko learns to better listen to her body and to “accept care and ask for what [she] need[s] from loved ones.” In other words, Tobimatsu and Geniza’s is a story of Kimiko gaining access intimacy with herself; it is a memoir that invites the audience to gain access intimacy with its narrator. Tobimatsu shares conflicts with her family, holds space for her break-up and the clumsiness of dating with her post-cancer symptoms, and finally being able to be vulnerable with her friends. This honesty about bodies and relationships is refreshing, both as a queer story and one about illness. Most of all, I loved how Geniza takes the reader from the close-up of text messages to the devastating, single-page winter scene of Kimiko’s breakup to the still moment when she washes her face in her bathroom, door ajar, lights on, by herself, but open—through the medium of the memoir—to being seen.

Jane Shi is a queer Chinese settler living on the unceded, traditional, and ancestral territories of the Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh First Nations. Her writing has appeared in Canthius, PRISM international, Briarpatch Magazine, and The Malahat Review.

Jane Shi is a queer Chinese settler living on the unceded, traditional, and ancestral territories of the Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh First Nations. Her writing has appeared in Canthius, PRISM international, Briarpatch Magazine, and The Malahat Review.