Review By Asam Ahmad

Near the end of The Ministry of Utmost Happiness, Arundhati Roy’s first new novel in twenty years, we find this passage jotted in a characters’ notebook:

How

to

tell

a

shattered

story?

By

slowly

becoming

everybody.

No.

By slowly becoming everything.

It is an awkward fragment, made more awkward by the way the text appears on the page. But this passage, which also appears on the jacket of the hardcover edition, signals one way to read what can charitably be called a “novel.”

This is not to say that this book is not worth reading. Fans of Roy’s writing do not need to be convinced of her poetic prowess or her staggering ability to condense millennia of history and wisdom into a few succinct sentences. But, perhaps precisely because Roy knows she has a built-in readership eager for more fiction, she does not seem particularly concerned about narrative conventions or the standard trappings of story, plot development, and structural cohesion here. This is particularly disappointing (and surprising) given the intricate and tightly contained architectural symmetry of The God of Small Things.

In The Ministry of Utmost Happiness, Roy has given us two separate narratives that never convincingly come together. One follows, intimately, the story of Anjum, a hijra* in Old Delhi, from birth as what the novel calls (in outdated and offensive terminology) a “hermaphrodite,” to her life as a woman living with other hijras, to her eventual settling into a small construction in a graveyard. The other follows S. Tilottama, a vagabond who falls in love with a Kashmiri resistance fighter and who seems to be modelled on Roy herself. The two stories fit uncomfortably, disjointedly together, and while the second half of the narrative has an intimacy that feels hard won, the first section following Anjum feels stilted and stereotypically tragic. It always feels like we are witnessing the world Anjum is a part of from the outside.

On the other hand, when Roy follows her protagonists to Kashmir, the narrative comes alive and bristles with an emotional honesty and intensity that is hard to adequately communicate. There are some passages that take the reader’s breath away, and Roy’s descriptions of how a people resist occupation, while heavily romanticized, are profoundly revelatory and quite beautiful. Take this passage, for instance, describing how suicide bombing entered the Kashmir valley:

When it [martyrdom] arrived in the Valley it stayed close to the ground and spread through the walnut groves, the saffron fields, the apple, almond and cherry orchards like a creeping mist. It whispered words of war into the ears of doctors and engineers, students, laborers, tailors and carpenters, weaver and farmers, shepherds, cooks and bards. They listened carefully, and then put down their books and implements, their needles, their chisels, their staffs, their plows, their cleavers and their spangled clown costumes. They stilled the looms on which they had woven the most beautiful carpets and the finest, softest shawls the world had ever seen, and ran gnarled, wondering fingers over the smooth barrels of Kalashnikovs that the strangers who visited them allowed them to touch. […] Only after they had been given guns of their own, after they had curled their fingers around the trigger and felt it give, ever so slightly, after they had weighed the odds and decided it was a viable option, only then did they allow the rage and shame of the subjugation they had endured for decades, for centuries, to course through their bodies and turn the blood in their veins into smoke.

This is an astonishing passage, not least because of how it syncretizes the cycles of violence and intimately connects the dots between the transformation of shame and subjugation into its opposite. The synecdochal metaphors build on each other, so that a Kalashnikov seems no different from “the looms on which they had woven the most beautiful carpets … the world had ever seen.” Roy is a master at communicating the ways in which violence seeps into the lives of ordinary people.But part of the disappointment of reading this novel is just how explicitly politics take centre stage in a fiction Roy has insisted on making us wait twenty years to read. We are given indexical accountings of almost all of the recent tragic histories of the subcontinent (and even Afghanistan and Iraq) over the past sixty or so years: Indira Gandhi’s assassination, the rise of Hindu fundamentalism with Prime Minister Modi, the 2003 Gujarat massacre, the Kashmiri occupation, the plight of Dalits (Untouchables), the Indian state’s war on tribal Adivasis in the forests of South India for mining corporations and profit extraction, the Bhopal massacre, the unending persecution of minorities, the internal wars being waged on and inside the bodies of hijras, the ongoing and unceasing patriarchal containment and subjugation of women. This is not a full list. Eventually, the dizzying accounting of violence blurs together. It is not only that Roy is not concerned with the narrative conventions of fiction, it is that she is perhaps not writing fiction at all but something altogether different. The dedication of this novel is to “The Unconsoled,” the capitalization underlining that The Unconsoled are multitudes upon multitudes that can never be fully represented on the page. At one point a protagonist apologizes for the chaos: “there’s too much blood for good literature” in the subcontinent.

For readers of Roy’s non-fiction, many of these issues will be familiar. But fiction is not meant only for the congregation: it is one of the only mediums through which the contradictions and nuances of ordinary life can be grappled with. For all the intricate history and chaos presented here, the moral of the story seems determined in advance and the good guys are easily discernable from the bad. The insistence on wanting to tell everyone’s story means there is very little life in the stories we are told. That, perhaps, is the point of telling everyone’s story: each becomes less meaningful as we whir from one catastrophe to the next, without ever really having time to grapple and sit with the catastrophes we have already been made witness to.

* Hijra, from Arabic meaning “to take flight” or “emigration,” is an ancient South Asian term for transgender people. The (recorded) presence of hijras dates as far back as four thousand years.

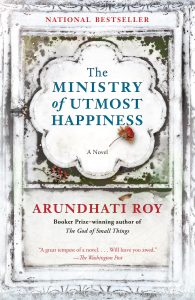

Arundhati Roy, The Ministry of Utmost Happiness (Penguin Random House, 2017). Hardcover, 445 pp., $35.00.

Asam Ahmad is a poor, working-class writer, poet, and community organizer. His writing tackles issues of power, race, queerness, masculinity, and trauma. His writing and poetry have appeared in CounterPunch, Black Girl Dangerous, Briarpatch, Youngist, and Colorlines. His poem “Remembering How to Grieve” can be found in Killing Trayvons: An Anthology of American Violence.