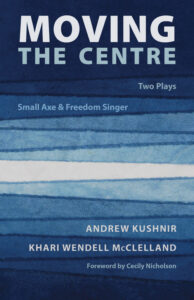

Andrew Kushnir & Khari Wendell McClelland, Moving the Centre (Talonbooks, 2022), 160 pp., $19.95.

Moving the Centre consists of two documentary plays, “Small Axe” by Andrew Kushnir and “Freedom Singer” by Khari Wendell McClelland, as well as accompanying essays. Relying on sources pulled from original interviews, historical records, and personal experiences, both artists explore themes of race, connection across place and time and personal excavation while examining societal structures.

In Slouching Towards Bethlehem, Joan Didion writes, “writers are always selling someone out.” This attitude was prevalent among my college professors: when making art, the hurt feelings of others are collateral damage. However, other schools of thought suggest we should consider the social ramifications of our work, examine our biases, and question our “right” to tell certain stories. This means that if we believe in something—say, justice, inclusivity, and accountability—we should do something about it. Small Axe is Andrew Kushnir’s attempt to do something about it.

Small Axe follows Kushnir (playing himself) as, after a conversation with a friend of Jamaican descent, he seeks to gain knowledge about the way Black people experience homophobia, both abroad and in Canada. He interviews over a dozen subjects: refugees, community leaders, Pride Parade revellers. The project goes off the rails as the subjects become interviewers, questioning Andrew’s motivations, assumptions, and intentions. What is he, a white man, going to do with their stories? With growing horror, Andrew realizes that he might be complicit in the oppression he’s seeking to expose.

Kushnir works to strike a balance by foregrounding his subjects and utilizing verbatim theatre. All of their dialogue, which includes anecdotes and thoughts on family, church, slavery, colonialism, and culture were pulled directly from interview transcripts with the real subjects. The stories are told by those who experienced them. He also employs a reversal of their roles: the characters directly challenge him, they move into the audience, and tell him: “work on your shit.” This results in a climax where Andrew attempts to dismantle the scaffolding on his own set.

It’s paradoxical: things cannot be presented exactly as they happened. The original subjects aren’t on stage and the content has been reorganized for better flow. Kushnir controls what the audience experiences and when. As much as he desires to minimize his part, he can’t remove it while also telling this story. This is an intriguing internal conflict. Small Axe is not perfect—it’s not “tidy”—but it is an ambitious work that seeks to “pass the mic” and move the centre of power. In this way, it’s essential that this play is read alongside the second play of the book, Freedom Singer, which is a perfect spiritual complement to Kushnir’s work.

In Freedom Singer, Khari Wendell McClelland finds a new connection with his ancestor Kizzy, an enslaved woman who fled to Canada and returned to Detroit after slavery was abolished. The play depicts McClelland’s journey to find more information on Kizzy, with a focus on the songs she might have sung on the underground railroad.

Freedom Singer demonstrates how hybridizing verbatim theatre with other forms (in this case, musical concert) can result in exciting creative outcomes. Even though I read the play, rather than seeing it performed, I was struck by its sound design. Ambient sound effects, repeating beats, and rolling riffs orient the audience in McClelland’s journey and contribute to the flow of the story. Whereas Small Axe relies on the actors’ voices, Freedom Singer incorporates actual recordings of interviews, conversations, song fragments, and historical sound bites into the play. The cast interacts with the included media with a great sense of duty and play—sometimes contextualizing it for the audience, other times engaging with it like an off-stage co-star, and occasionally embodying the character. There’s even a full-blown re-enactment of a 1991 Heritage Minute that had me laughing (and cringing).

Interwoven throughout the play are the songs McClelland is searching for—a mix of original and reimagined abolitionist songs that he utilizes to cement the connection between past and present, between Kizzy and himself. A moving example of the way song operates within the play is a 1943 recording of William Riley, an elderly man and escaped enslaved person. As McClelland points out, it’s rare to hear the voice of someone who lived during American slavery. When Riley sings “No More Auction Block for Me,” it’s powerful. The cast then perform the song themselves, shifting Riley’s lyrics from “no more auction block for me” to “no more crooked cops” and “no more poisoned land and sea,” connecting the oppression of Kizzy’s time to that of McClelland’s.

This also exemplifies a major theme of the book in general: iteration. As McClelland explains in his accompanying essay, this work is “less about the perfection of a single offering and more about how it might lead you to your next iteration as an artist and human being.”

Moving the Centre is a stirring, philosophical, and challenging read. I wish I could tackle it in a classroom or even a book club—there’s so much to chew on, from the technical aspects of the form to the exploration of the ways racism intersects with art, history, power, and purpose. It examines the connection between intention and outcome, between creator and consumer, between ancestor and descendent. While neither Kushnir nor McClelland resolve the inciting incidents that spark their plays, they achieve a deeper goal of “[t]rying again and again to get closer to truth, revelation, and grace.”

…

Cara Kauhane is a writer from Vancouver. Her work has appeared in The Ampersand Review, The Capilano Review, Fugue, and Memewar.

Cara Kauhane is a writer from Vancouver. Her work has appeared in The Ampersand Review, The Capilano Review, Fugue, and Memewar.