A Q&A with Amanda Merpaw, Plenitude Magazine

In connection with the annual Victoria Festival of Authors taking place October 15 to 19, 2025, Plenitude poetry editor Amanda Merpaw interviews Jess Housty.

Jess Housty (‘Cúagilákv) is an Indigenous parent, herbalist, and award-winning poet. Their work in the non-profit sector supports Indigenous cultural resurgence, land protection, food sovereignty, and climate organizing in their Heiltsuk territory and beyond. They live in Bella Bella, B.C., surrounded by extended family and nonhuman kin.

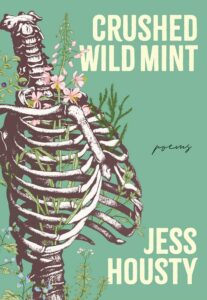

Winner of the 2024 Dorothy Livesay Poetry Prize and the Bill Duthie Booksellers’ Choice Award, Crushed Wild Mint explores land love and ancestral wisdom. Rooted in the poet’s motherland and shaped by their roles as parent and herbalist, these poems move between body and land, grief and love, where natural and ancestral worlds converge.

Amanda Merpaw (AM): The first poem in your collection Crushed Wild Mint closes with the lines, “Praying is dreaming out loud / with my ancestors; // praying is giving a voice and anatomy / to futurity.” Many of the poems in the collection open with lines about prayer, weave the practice of prayer throughout, or feature the word prayer in their titles. What does prayer mean to you? What do you see yourself dreaming of in these poems? What future do you hope to give voice to?

Jess Housty (JH): Prayer, for me, is the act of offering a gift of connection to another entity, human or nonhuman. Prayer connects me to myself, my ancestors, my kin, my land. It enables me to reach toward something or someone I love and speak to their sacredness. I’m often asked if I’m religious, and I’m not. But I have a deep reverence in me, and an unflagging belief that holiness and wonder are far more widespread than we can possibly imagine. We just need to invite connection. That’s the only future worth creating, for me — one rooted in kinship and community and the power of mutual witnessing.

Jess Housty (JH): Prayer, for me, is the act of offering a gift of connection to another entity, human or nonhuman. Prayer connects me to myself, my ancestors, my kin, my land. It enables me to reach toward something or someone I love and speak to their sacredness. I’m often asked if I’m religious, and I’m not. But I have a deep reverence in me, and an unflagging belief that holiness and wonder are far more widespread than we can possibly imagine. We just need to invite connection. That’s the only future worth creating, for me — one rooted in kinship and community and the power of mutual witnessing.

AM: In addition to being a poet, you’re also an herbalist and land-based educator. The poems in this collection are abundant “with the flora who are our kin,” with the medicine of the land, with harvest and healing. Is there a connection for you between the work you do as a poet and the work you do with the land? Do you see poems as a form of nourishment? Or, as you write in “Bowing to Yarrow (II),” as “small acts of healing and propagation”? Are there limits to what a poem can and cannot offer?

JH: It’s all the same work to me: it’s all making a space for reverence and reciprocity. There is a mutuality in my relationship with plants rooted in reciprocal caretaking and shared medicine, and in those acts of shared medicine we build kinship. Poems are another kind of medicine and it’s a privilege to be part of a conversation through poetry, both as a writer and a reader, in which I am nourished and try to offer nourishment in return. A poem cannot break a fever like yarrow can, or clear the lungs like usnea, but it can nourish — it can heal — by offering a point of connection.

AM: One of the throughlines of this collection is the importance of family and ancestry—both what we inherit and what we pass along. Who or what do you see as your poetic lineage? What poets, writers, artists, family and community members, beings and places have influenced you in your poetic work?

JH: I grew up with storytellers and oral historians who gave me such a rich understanding of how place and kinship and culture braid together into shared identity. My grandfathers, in particular, animated my understanding of the world and my place within it through their magnificent storytelling. But I also feel indebted to so many of the poets whose work I encountered young — Wendell Berry, Mary Oliver, Jim Harrison, Sharon Olds, Lorna Crozier, Susan Musgrave — who showed me how to be a human being who is capable of being an attentive and loving and truthful witness to the world around me.

AM: Many of the poems in Crushed Wild Mint are addressed to a “you,” though the addressee differs: sometimes it’s a child, a grandparent, a lover, the reader, and beyond. What draws you to this form, this poetic address? What does it make possible for you in these poems? Do you imagine the speaker of the poems also differing throughout the collection?

AM: Many of the poems in Crushed Wild Mint are addressed to a “you,” though the addressee differs: sometimes it’s a child, a grandparent, a lover, the reader, and beyond. What draws you to this form, this poetic address? What does it make possible for you in these poems? Do you imagine the speaker of the poems also differing throughout the collection?

JH: My favourite poems as a reader are the ones that invite me into a sense of shared intimacy. I love poetry that is accessible, that holds out a hand to people and encourages them to imagine themselves into the lines. I hope that when I address poems to an unspecified “You,” that readers press their fingers to their chest for a moment and respond with a quiet, “Me?” Maybe it’s a little silly, but I believe we thrive through our sense of connection and it feels important to offer connection when I can. The poems are so deeply personal that I don’t think the speaker changes — but there’s always a chance the addressee might be you.

AM: There are titles and poems throughout the collection that incorporate Heiltsuk words. Why was it important for you to weave Heiltsuk into your poems and to let it stand on its own without immediate English translation? How did you come to the decision to include the glossary at the end of the book?

JH: Every Indigenous writer I know has a different relationship to their language. I am not a fluent speaker, though I hope to be someday. Much of my work outside of writing focuses on supporting youth in my community to be part of culture and language resurgence. And I feel a debt to those kids, and to the elders who held tight to our language and ceremony for generations, to use whatever power and privilege I have to build up our cultural resilience. One way I try to honour that task is by incorporating our language into my book and letting those words stand in their own strength. I’ve been criticized at times for making readers take on the extra labour of flipping to the glossary and translating, but our language is beautiful and strong and worth the momentary discomfort of knowledge-building.

AM: I was struck by the beautiful tenderness and deep love that flows through these poems, from the speaker to family, ancestors, ghosts, community, land, water, animals, and plants, and also between all of these. In “12.15.21,” a poem for bell hooks, you write, “If love is an action / (and it is), / becoming an ancestor / must be an act of perpetual love; // let our loving be a discipline.” What does it mean to act with perpetual love, for love to be a discipline? What role does love play in your life and in your work?

JH: Sometimes I wonder if people get tired of listening to me talk about love. I think that love is what binds us — what heals the ruptures — what magnifies the joy. And it’s hard work. When I love someone, human or nonhuman kin, when I choose that relational approach, it comes with a commitment to accountability and reciprocity over time and without reserve. That’s where loving becomes a discipline. I choose love over and over and I choose to let love in. It’s intimate and it’s vulnerable and you are never, ever alone in anything you’re carrying. And when we build a discipline of connection, we build the kinship and community that will enable us to survive and thrive.

Amanda Merpaw (she/her) is a queer writer and editor from Ottawa, currently based in Toronto (Treaty 13). She is the author of the collection Most of All the Wanting (Palimpsest Press, 2024) and the chapbook Put the Ghosts Down Between Us (Anstruther Press, 2021). Amanda has been a finalist for Arc’s Poem of the Year contest, The Fiddlehead Fiction Contest, and the Montreal Fiction Prize, and her writing has appeared in various magazines, including The Capilano Review, CV2, Grain, and Prairie Fire. She is English Program Director at Poetry in Voice/Les voix de la poésie and a member of the editorial board at Anstruther Press.

Amanda Merpaw (she/her) is a queer writer and editor from Ottawa, currently based in Toronto (Treaty 13). She is the author of the collection Most of All the Wanting (Palimpsest Press, 2024) and the chapbook Put the Ghosts Down Between Us (Anstruther Press, 2021). Amanda has been a finalist for Arc’s Poem of the Year contest, The Fiddlehead Fiction Contest, and the Montreal Fiction Prize, and her writing has appeared in various magazines, including The Capilano Review, CV2, Grain, and Prairie Fire. She is English Program Director at Poetry in Voice/Les voix de la poésie and a member of the editorial board at Anstruther Press.