In Scarborough, Catherine Hernandez’s new novel, a cacophony of voices intermingles to create a unique portrait of the many disparate communities that make up one of the largest and poorest suburbs in Canada. Hernandez carefully weaves many different characters from many different social locations and demographics to tell the story of Scarborough, and while the novel suffers from the weight of so many disparate threads, there are many beautiful gems here that make this book worth reading.

The narrative opens with a brief scene of Laura, a young white girl, escaping an abusive home in the middle of the night with her mom. Throughout the text, Laura is neglected by those who are supposed to care for her and finds meaningful moments of intimacy and connection with strangers and caregivers around her. Laura’s story opens and closes the narrative; her fate places her at the centre of much of the narrative thrust of the novel.

gravitational centre of the novel, however, is the community drop-in program for young children at the Rouge Hill Public School. We are introduced to the centre via an exchange of letters between Hina Hassani, the hijabi woman who has been hired to run it, and her boss, Jane Fulton. These letters are dispersed throughout the novel, detailing the growing tensions between boss and worker, as Jane continually overwhelms Hina with demands for more (unpaid) labour from her office in downtown Toronto. Hina takes care of many of the kids who appear in the novel, including main protagonists Laura, Sylvie, and Bing. The centre works as the physical and metaphorical heart of the book, and many of the characters meet each other there. Hernandez expertly communicates the difficulties of working in a large non-profit, as well as the joys and exhaustions of frontline work.

But Scarborough is not a straightforward novel in terms of plot and exposition. Hernandez gives us brief glimpses of each character’s life in small vignettes, before moving on to new characters or returning to previous threads, and we are introduced to an abundance of voices almost immediately. Some of these voices work better than others. Sylvie and her mom are trying to survive life in a shelter, along with Sylvie’s younger brother Johnny, who has a learning disability and may be hearing impaired. At the shelter, we are briefly introduced to Mrs. Abdul, who jealously guards the shared kitchen, and Mr. George, an elderly Ojibwa man who breathes through a hole in his throat and is tasked with looking after Sylvie and Johnnie when their mother needs to take care of urgent errands. There is also Edna, the Vietnamese mom who manages a nail salon and whose son Bing is on the verge of coming out; Winsum, a West Indian restaurant owner tired of explaining spice levels to white people; Cory, a former white supremacist who deeply despises all of the racialized ethnicities around him and, as Laura’s dad, is also usually too drunk to take care of his young daughter; Victor, a young Black artist harassed by the police; and many others.

Because Hernandez wants to tell so many different stories, sometimes it feels like we are only getting brief and perhaps superficial glimpses of some of these characters’ lives. The only narrative for Victor revolves around him getting harassed by police officers as he paints a mural, which reads as little more than a story ripped from the headlines, without adding anything to who Victor might be or what other forces have shaped his life beyond his interactions with the police. Similarly, Winsum is given a single chapter detailing the events of one Christmas eve and then disappears from the narrative.

The novel suffers from this gamut of voices, and sometimes it reads as if Hernandez felt obligated to represent every single kind of ethnicity found in Scarborough—sometimes to the detriment of the voices she has already introduced. To me, someone who grew up in Scarborough, many of these stories felt familiar, but they also seemed to crowd each other out. Perhaps the form is meant to convey what it is like to live in Scarborough, shaped as it is with so many different facets.

The narrative fleshes out the stories of Sylvie, Johnny, and their mom, as well as Bing and Edna, more than others, and these are some of the best sections of the book. Bing is a gifted student and his connection with his mom is beautifully rendered. Sylvie’s dad is injured before the narrative opens, and we are never given the full story of what happened to him, or his relationship with the family. Characters who look and sound like Sylvie and Bing rarely appear in Canadian literature, and I wish Hernandez had spent more time detailing the histories, contexts, and interiority of these characters’ lives.

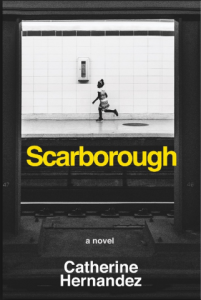

Catherine Hernandez, Scarborough, (Arsenal Pulp Press, 2017). Paperback, 254pp., $17.95.

Asam Ahmad is a poor, working-class writer, poet, and community organizer. His writing tackles issues of power, race, queerness, masculinity, and trauma. His writing and poetry have appeared in CounterPunch, Black Girl Dangerous, Briarpatch, Youngist, and Colorlines. His poem “Remembering How to Grieve” can be found in Killing Trayvons: An Anthology of American Violence.