Reviewed by Gwen Benaway

Reviewed by Gwen Benaway

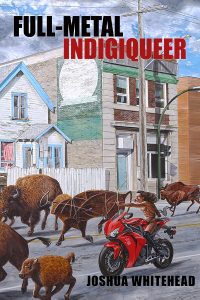

Joshua Whitehead’s debut collection of poetry, full-metal indigiqueer, is a cyberpunk dystopian vision of modern queer Indigenous life. Influenced by the classic Japanese anime Akira, full-metal indigiqueer is one of the most distinctive and original collections of Indigenous poetry ever published. It blends Indigenous futurism with colonial hangovers in dense text that scrolls across the page as if spit out by an old dot matrix printer possessed by an NDN ghost. The strongest feature of Whitehead’s work is how his writing blends genres, poetic influences, Cree and English language, and queer embodiments into a strange poetic cyborg.

For example, the poem “April 5: Pass [Hang] Over” starts off with a nostalgic reference to the television show Roseanne and the speaker’s terror at his identification with Darlene. Transitioning into memories of staying up late while his parents work at “ikwe widdjiitiwin,” the speaker describes watching late-night queer television, particularly Queer as Folk and Kink on Showcase. He writes “catch brent everett and brent Corrigan/in a brokeback mountain parody” and “feel guilty about jacking-off to badboyton and mike18”. The layering of 1990s and early 2000s queer media figures and gay porn stars with Cree words creates a striking dissonance between the traditional and the digital, between Creeness and whiteness. He closes out the stanza with the lines “I was making mirrors out of white queers / whereami / whereami / whereami / i /I [question mark].”

This looping of a Cree self, interjected into digital narratives of white queerness, delineated by poetic coding breaks and text insertions, frames the entire collection. Located inside Creeness, the sense of being dislocated from ancestral ways of being by violent colonial interventions, the speaker in full-metal indigiqueer alternates between interrogating the inherent whiteness of queer culture and mourning their particular longing for safe access to queer desire and community. In a poem called “To My Mister Going to Bed,” the speaker states, “tell me: ‘i didn’t think gay natives still exist,’” a reflection on the seeming impossibility of being queer and Indigenous. Throughout the collection, there are scattered snippets of conversations with white queer men, centred on the ways these sexual interactions replicate notions of colonial possession and research with the speaker’s body.

It is difficult to summarize the collective narrative of full-metal indigiqueer because the collection is determined to escape any easy answers. Whitehead continually returns to the site of colonial desire and the intersections of Creeness, queerness, and the body throughout the collection, asking the questions “where am I” and “what am I” over and over again. The figure of the speaker’s kookum (grandmother) appears throughout several pieces, a small brown Cree woman embedded into the speaker’s memories. She is often balanced against the speaker’s recollections of their family’s violent colonial past and their current experiences of the same colonial violence inside queerness. The grief around the death of the speaker’s kookum is always present, becoming one of the main threads within the collection. While the grief is clearly rooted in the speaker’s love of their kookum, it is also a complicated grief of missing ancestral knowledge, a solid connection to Cree worldviews, and a longing for traditional legends, language, and homecoming.

over and over again. The figure of the speaker’s kookum (grandmother) appears throughout several pieces, a small brown Cree woman embedded into the speaker’s memories. She is often balanced against the speaker’s recollections of their family’s violent colonial past and their current experiences of the same colonial violence inside queerness. The grief around the death of the speaker’s kookum is always present, becoming one of the main threads within the collection. While the grief is clearly rooted in the speaker’s love of their kookum, it is also a complicated grief of missing ancestral knowledge, a solid connection to Cree worldviews, and a longing for traditional legends, language, and homecoming.

Several lines in the collection haunt me. They manage to cut through the digital and pop-culture background noise of the collection to emerge as striking and resonant articulations of Indigenous queerness. I love the stanza in “D Pairs Well with Vowels” that simply states, “can’t i just be a body that loves [questionmark] / why do i have to be a thing [questionmark] / I exist in the bone / and nothing really matters.” It might be tempting to read the speaker as desiring a form of queer misidentification, to be erased of all identities and granted the assumed neutrality of white bodies. For me, as an Indigenous transsexual, I see these lines as speaking to the desire of many Indigenous bodies to escape the constant colonial pressure of the world around us. I read Whitehead’s argument for a return to our traditional ways as an escape back into the intellectual and emotional sovereignty of our nations, a way to finally stand within ourselves outside of colonization, queerness, or whiteness.

In the final poem, “I Can Be a Dream Girl Too,” the speaker writes, “i have to stop myself / remember my people are dying / during every metaphor in this poem.” This reference to the ongoing genocide of Indigenous bodies in Canada is a powerful one which underscores much of Full-Metal Indigiqueer. Whitehead grapples with the questions of Indigenous survival, revitalization, and embodiment within queerness and inside a colonial culture, which resonates with me.

Joshua Whitehead, full-metal indigiqeer. (Talon Books, 2017), paperback, 128pp., $18.95

Gwen Benaway is of Anishinaabe and Métis descent. She has published two collections of poetry, Ceremonies for the Dead and Passage, and her third collection, Holy Wild, is forthcoming from BookThug in 2018. A Two-Spirited Trans poet, she has been described as the spiritual love child of Tomson Highway and Anne Sexton. She has received many distinctions and awards, including the Dayne Ogilvie Honour of Distinction for Emerging Queer Authors from the Writer’s Trust of Canada. Her poetry and essays have been published in national publications and anthologies, including The Globe and Mail, Maclean’s Magazine, CBC Arts, and many others.