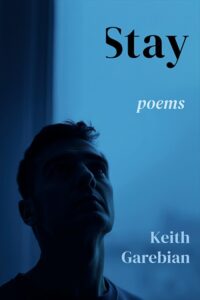

Keith Garebian, Stay (JLRB Press, 2024), 85 pp., $19.99.

There are books you encounter, on occasion, that leave space for you… space where it can feel like you’re living alongside the poet, their accumulated line breaks and stanzas brush up against your own memories, so it’s as if you’re reading and reliving simultaneously. After reading Keith Garebian’s new collection of poems, Stay, a deluge of my own experiences tumbled down so much so that I had to re-read the book to make sure I could differentiate between what this queer elder has offered, and my own mid-life recollections of love and loss.

Garebian, a student of Commonwealth literature with a specific interest in poetry and plays, opens this collection (his thirtieth book) by quoting the late queer trailblazer, Robert Duncan, whose poem “The Torso” accentuates the dizziness of infatuation, contrasting capital-T Truth with illusion. This sets the stage for the series of poems that detail the love affair between the protagonist and his object of affection, a somewhat younger man.

Not every love can be the first, and Garebian’s Stay is an exercise in both anticipation and recognition. Tethered across four discrete sections, Stay takes the reader on a journey that feels as much about self-discovery as it can be about giving up old ideas of who we think we are, or how we may be perceived through our relationship with someone else.

Tellingly, the first section, “Magic Mirror,” begins by recognizing the societal expectations placed on a young person wanting to explore and discover who they might one day become. Here we are introduced to a dreamer who will “come of age / in a gridwork of laws,” who must learn to swim underwater for protection, and then eventually emerge a “swanlike femme” during a midday hotel-room meeting. This object of consideration—the young man, questioning and closeted—we learn is married to a woman and together they have a son, and have immigrated to Canada. Presumably, this is where the narrator meets him, where still “thoughts growing / like roots that dream in the dark.” The section ends with the elliptical moment of shock at a certain turn-of-phrase, the concluding line of “The Words He Will Never Say” (p. 10): “He wants to strip the moon’s halo / the way a brutal man wants to / break into a virgin youth.”

The second section, “This Wild Sweetness,” introduces the location of a bathhouse as the chance meeting place where the protagonist poet elucidates all things physical and libidinal across several of these poems… each depicting a different man, or exploring the archetype of Gay (capital-G) bodies, with reference to Apollo, “sculpted pecs,” wolf-like zeal, “bodybuilder frame,” and more. Here Garebian’s impression of a bathhouse and its visitors feels erotic, yes of course, but darkly so… though not without merit; I love the lines, “In the dark, shadows kneel before shadows; / they worship each other–” (“The First Time,” p.15), as well as “My many flames have singed / into my view an erotic eclipse” and “old sighs made new” (both from “Spending Again What is Already Spent,” p. 19). Tapping into the sounds of these often dark places makes sense and adds another dimension to the telling of this story.

Anyone who has ever tried, or those of us well read in the genre, knows how incredibly difficult it is to write erotic poems without coming across as cliché. Stay walks this fine line, at times a bit too demure only to give into the temptation of certain metaphors, without which ultimately the story might not resonate.

I appreciated more of the poems that comprise the third section, “Poems at the Edge of a Cliff,” for their lust-filled and playfully honest depictions of queer love/non-heteronormative life. Here, the poet experiments with form in a more direct way; lines such as “We recite to each other poems / at the edge of a cliff – / dream poetry, / dream cliff” feel playful and surprising. Whereas “Almost a Sunset” (p. 40) reminds me of a specific instance in my own past, a younger lover who I would read to in bed echoing Garebian’s assertion, “he tells me it isn’t just the sex / that he cares for, but what I know, / my way with words.” Intimacies, such as these, are expanded upon through the routine of day-to-day life, small but meaningful anecdotes, and the laugh-out-loud hilarious sequence from the poem “Throuple”: “It’s a neologism: / a three-way, an online in-joke: / twice the sex, with six times / the emotional baggage” [I can corroborate this math].

Haven’t we all, or might not any of us wind up, the older of two (or three) in a love affair?

The eponymous concluding section presents its inevitable opposite—the departure of the younger lover. The poems that wind down the book offer a flurry of recollections, reiterating various places and sequences from the earlier pages, driving home the reality that these men did share time, and life, and love. In another sort of callback (this time to the Duncan quote that started the collection), Garebian’s “Poem from the First and Last Lines of Justin Chin” is where we find this collection’s title: “In the morning / grief comes in waves // stay.” To call into breath the name of two dead queer poets carries importance, strength, and generosity. Justin Chin (1976-2015) was an Asian American queer poet who died after a massive stroke, leaving his community in shock and understanding that sometimes the most profound love affairs are the briefest. Garebian’s “Our Goodbye” ends with a similar sentiment, “Our time together moved / much too fast – / did you know we were birds // flying headlong into the glass?” [I remember penning notes for a poem comparing all of my boyfriends to various birds, falling, falling, falling.]

I finished this text on my friend Marian’s birthday. When I was getting ready to leave my former home of Winnipeg, I found myself in a barrage of text exchanges with Marian, lost track of time, and wound up missing my flight to what would become my new home in Victoria. This country is so big that the next flight wasn’t scheduled to leave for another eight hours. I’d left my keys behind, with my ex and our dog, and wound up in the purgatory of the Winnipeg airport. What there isn’t room to write about here is the love affair with a younger man that shipwrecked my life in such a profound way that I’m only now picking up the pieces. Brushing up against my own memories, nestled in the pages of Garebian’s Stay.

Originally from Winnipeg, Kegan McFadden is an artist, curator, and writer living on an island in the Pacific Northwest. Over the past twenty years, his criticism and related writing has appeared in Border Crossings Magazine, Canadian Art, CV2, Fuse, Galleries West, GayLetter, poetry is dead, and Plenitude, in addition to numerous gallery publications across Canada.

Originally from Winnipeg, Kegan McFadden is an artist, curator, and writer living on an island in the Pacific Northwest. Over the past twenty years, his criticism and related writing has appeared in Border Crossings Magazine, Canadian Art, CV2, Fuse, Galleries West, GayLetter, poetry is dead, and Plenitude, in addition to numerous gallery publications across Canada.