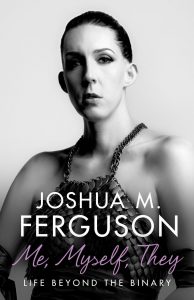

When I opened Me, Myself, They, I knew nothing about Joshua M. Ferguson. I didn’t know that as a political activist they had pioneered policy changes in Ontario and B.C. that now permit non-binary gender identification on birth certificates and driver’s licenses. Further, I was unfamiliar with their work as a documentary filmmaker. I assumed that I would be reading a fairly standard identity memoir about what it’s like to be born in the wrong body and undergo the challenges and risks of transitioning to life as a different sex.

I quickly realized that this is not such a transition story. Rather, it’s the account of a person who feels oppressed and rendered invisible by the forced identity that social convention imposes on the psyche because of the biological maleness or femaleness of the body at birth, and who cannot rest until they change that situation. This is the crux—and the value—of the book. Ferguson, and many others, are neither male nor female, but rather something non-binary and fluid: they are they.

Ferguson was the eldest of three children, raised in Ontario in a well-educated, professional family. Their dad was a wildlife biologist and their mother a psychiatric nurse. Their youth was mainly spent in the small town of Napanee, which lies between Kingston and Belleville, a bit inland from the shores of Lake Ontario. It’s a town without much in the way of cultural amenities; narrow, conservative, unfriendly to alternative lifestyles and identities: a lot like my memory of London, Ontario, where I grew up half a century ago.

From an early age, Ferguson was driven to display a unique gender identity in that alien and fundamentally hostile environment; unsurprisingly, the result was bullying, ridicule and exclusion. They discovered an alternate world in online fantasy games, along with a group of people who accepted them; through the games, Ferguson could create the persona of female power that they truly wanted to be. This was a lifeline in the loneliness and despair of adolescence, especially when the school effectively blamed young Ferguson rather than their oppressors for the bullying that they endured. The school suggested that they leave.

While they emphasize again and again that both parents did their best to love and support them in the risks and struggles of discovering their true identity, the family had more than its share of troubles. Their mother left in their teenage years; their dad attempted a dramatic suicide, which involved police intervention; and their mother subsequently hospitalized herself for bipolar disorder and suicidal ideas. Ferguson survived, damaged and unfocused, into their early twenties. That’s when they had the inspiration that changed their life: they would tell stories like their own, to help other people. They went to University of Western Ontario where a couple of teachers opened up new philosophical and aesthetic worlds; they met like-minded peers, one of whom they ended up marrying—and eventually relocated to Vancouver where they and their husband began making successful documentaries, and where Ferguson completed a doctorate.

That’s an impressive story, and an encouraging one, certainly for people who are constructing identities as trans or non-binary or gender non-conforming—but also for all of us who have been excluded, bullied, marginalized, and abused.

Not that gender fluidity is anything new, as Ferguson points out. Two of the guiding stars in my own firmament, Shakespeare and Jesus, are obviously non-binary: a rich and complex mixture of male and female identities. That’s the source of their immense empathetic power, and with it, their wisdom. And if we’re honest, can any artist claim to be exclusively “male” or “female”?

I myself have a stake in this story. I grew up in the 1950s, a radically different era. I was uncomfortable in my own assumed identity as a little boy. I played with girls; I demanded dolls for Christmas; I dressed up as a woman—before I understood that cross dressing was taboo; to my father’s shame, I avoided sports and the competitive world of my male peers. If I’d been born in the 80s or 90s, I think I would have self-identified as trans or non-binary, a choice unavailable in my day. Like Ferguson, I suffered a lot, and (unlike them) I made major mistakes in trying to live a so-called “normal” life as a heterosexual “cis male.” Those mistakes had horrifying consequences. Other people suffered and remain deeply scarred, because of me. It’s their suffering, not my own, that haunts me now.

In their final chapter, Ferguson cites some studies that show how radically societal notions of gender are now changing, and that’s an encouraging thing. According to one study, a third of millennial (people born in the 1980s) and almost half of “Gen Zers” (people born between the mid-nineties and the early years of this century) identify as a sexual orientation other than heterosexual. They also quote a big California study that finds that twenty-seven percent of that same age group either have, or are perceived as having, “a gender-nonconforming expression” in the way they live. That’s a change for the better, as impossible to imagine in my early years, as in adolescent Ferguson’s Napanee.

While rooted in Ferguson’s often painful experience, Me, Myself, They is structured and written more like a book-length essay than a memoir: it’s mostly “tell” rather than “show.” As such, the voice can be repetitive, and sometimes I feel that I’m reading a somewhat doctrinaire rant. But the honesty is always there—even in their refusal of an easy and conventionally happy ending.

That’s one of the most touching, and troubling, aspects of the story. Ferguson continues to struggle with depression, and a continual need for the affirmation of others. Their life remains arduous and open-ended, despite its success. The story isn’t over by any means; indeed, as they themselves say, referring to the transition from “me” to “they” that gives the book its title, “finally, my story can have its true beginning.”

Joshua M. Ferguson, Me, Myself, They (House of Anansi, 2019) 304 pp., $22.95

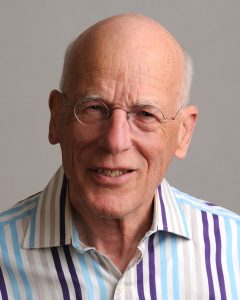

Jeremiah Bartram won a Jessie Richardson Award for his first play, The Wolf Within, about a gay priest coming to terms with his identity. He has been silent for a long time, but recently began writing again, with an MFA from University of King’s College and some work for CNQ. He is writing a book on puppet theatre and lives with his puppets in Ottawa. Visit his website at www.jeremiahbartram.com.

Jeremiah Bartram won a Jessie Richardson Award for his first play, The Wolf Within, about a gay priest coming to terms with his identity. He has been silent for a long time, but recently began writing again, with an MFA from University of King’s College and some work for CNQ. He is writing a book on puppet theatre and lives with his puppets in Ottawa. Visit his website at www.jeremiahbartram.com.