Zachari Logan, Green (Radiant Press, 2024), 166 pp., $25.

Say one were to pull Zachari Logan’s Green off a shelf and flip through it; the effect of letting the pages release under one’s thumb like a kineograph would illicit its own sensations even before one read the words within.

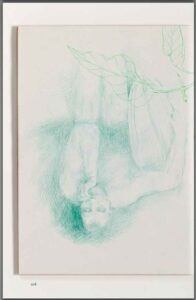

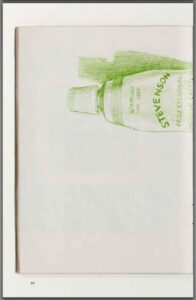

In the first sentence of the preface, Logan admits, “The thingness of a book, its tangible, aesthetic qualities interest me greatly, maybe too much.” This is deeply felt in Green. Between Logan’s poems and essays—cushioned in the center of the book—are scanned images of his own sketches rendered in green ink, pencil, and marker, from a notebook the artist kept for several years documenting everything from tulips and wildflower seeds to a tube of paint and a tapestry hanging in the Met Cloisters. (It should be noted the typography in Green is also green).

What does placing text and drawings within one binding do to the reader’s experience of a book? In Green, Logan’s sketches are not mere supplement to his poems—they are given equal reverence and space. This commingling of different forms has the effect of blurring the lines between textual and visual. “Drawing, while its own conjuration, requires a very similar interchange to writing,” Logan writes in the preface. This sentiment is reminiscent of what Pablo Picasso once said: “You can write a painting in words, just as you can paint feelings in a poem.”

Page excerpted from Green by Zachari Logan, published by Radiant Press, 2025. Reprinted with permission from the publisher.

What makes Green all the more interesting is that the interchange between art and writing doesn’t stop there. Many of the poems in this collection are ekphrastic (notably, “Notes on Caravaggio,” “Sofia,” “El Greco,” “Tom Thomson, the Dream,” “The Unicorn Tapestries,” “Hilma”)—describing the experience of viewing a physical piece of art. A domino effect of interpretation takes place: the art object is seen and felt by Logan at one time and place and transmitted to the reader to see and feel again through the poems on the pages of Green. Or in Logan’s words: “Spell the surface / of skin with marks / that pour out / into eyes, / an enchantment.” (“Drawing”).

Much of Green is about making marks. Beyond the rudimentary pencil, pen, and paint, Logan suggests other artistic mediums can be found in the mundane and metaphorical—bruises, shadows, the sun’s afterimage on closed eyelids, dirt, dust, scratches of a cat’s paw, the wind, a flattened spotted lantern fly on cement, footprints, clouds. But Logan acknowledges these marks are transient: “Nothing will last, / because nothing has ever been / the way I once perceived it.” (“Burgundy 1-17”). Herein lies one of the central tensions in Green. Even after a mark is made, a work of art is created, or a poem is written: it is never completed. The artist’s product ceases to be theirs, instead belonging to time and the slipperiness of perception. But Logan suggests this is not something to be mourned—impermanence must be accepted, celebrated even. This is explored in “The Tiger,” which begins:

A small painting of boreal tones

on faded greenish paper—At the composition’s perimeter

a tiger’s body slinks down a cliff.The once bright orange body

has almost gone pale.A reckoning with so many years

immersed in uv and the pressbetween old glass and parchment.

Page excerpted from Green by Zachari Logan, published by Radiant Press, 2025. Reprinted with permission from the publisher.

Logan presents the reader with an aging but startlingly alive composition. There is a suggestion of the original document—bright, crisp, colourful—and its transformation, its reckoning with time into something faded, yet renewed. By the end of the poem Logan concludes, “I cannot imagine this paper more beautiful / than now.” This is a gift—a perspective Logan has left for the reader to try on. What else becomes more beautiful over time? What unforeseen beauty has yet to transpire?

Logan’s scanned journal of sketches in the middle of the book physically illustrates this point: how time can recontextualize art and create new meaning. There are several instances where one can see that green ink has bled onto the other side of a journal page. This allows in some instances for the viewer to perceive a phantom image of a sketch underneath another one. For example, under a fine line drawing of a chapel interior, an outline of a butterfly is faintly perceptible. Likewise, a folded table umbrella under a houseplant; a lime-green feather behind a rendering of an artist studio. The reader sees the ink that bled through in spots Logan presumably pressed harder or created more saturated layers. By presenting the scanned images of the journal this way, whether intentional or not, Logan has called attention to these happenstance formations, which could only exist in accumulation over time, as he continued to add entries to the journal.

Page excerpted from Green by Zachari Logan, published by Radiant Press, 2025. Reprinted with permission from the publisher.

Green does feel like the result of the author’s preoccupation with the passing of time. However, this fixation is not based in the perils of what could have been or what could be. Rather, the focus is on what is this now? Logan offers a way out of the brambles of the past and the fantasies of the future: “Today is an ode. / Not yesterday, not tomorrow. / They are dirges; they do not exist. / Today is day one. / Today is an ode.” (“Today Is An Ode”).

Green is immediate, it’s happening as you’re reading it. It is not an artifact or a manifesto, it is a living artwork of various forms, expressions, and tensions. It requires the reader to participate and bring their own life materials to the page. This relationship between reader and author within the work allows them to bear witness to each other. Logan entreats, “Push back with all the strength of your roots, press against the weight / of my humanness.” (“Humanness”).

Mormei Zanke is a writer based in Brooklyn. She earned her MFA in literary reportage at NYU’s Arthur L. Carter Journalism Institute and a BA in English literature and creative writing from the University of British Columbia. Her poems and writing have appeared in publications including The Globe and Mail, KGB Lit, Kyoto Journal, PRISM international, and The Sunday Long Read.

Mormei Zanke is a writer based in Brooklyn. She earned her MFA in literary reportage at NYU’s Arthur L. Carter Journalism Institute and a BA in English literature and creative writing from the University of British Columbia. Her poems and writing have appeared in publications including The Globe and Mail, KGB Lit, Kyoto Journal, PRISM international, and The Sunday Long Read.