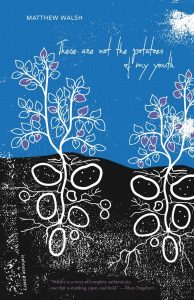

Matthew Walsh, These are not the potatoes of my youth (Goose Lane, 2019), 92 pp., $19.95.

I don’t want to have to use the word liminal, but all the spaces in Matthew Walsh’s debut poetry collection These are not the potatoes of my youth are absolutely liminal. Walsh is a Nova Scotia poet who lived on the West Coast for a while and now resides in Toronto; they have crisscrossed the country by bus several times and carry some sense of that movement into their poems, more concerned with space than geography—we may know all the points on the journey, but they begin to feel like transitory states rather than locations we move through. We won’t be stopping.

The state of being Walsh is getting at with this collection is explicitly queer, and revelation is always at our heels. Bone-deep in their lines is a sense that the speaker is moving through space not to go somewhere—not even to get away from somewhere—but because they don’t belong anywhere, a fact that is always just about to be revealed. They must always be ready to evacuate.

(And I want to say that it feels disingenuous to use the speaker here, because I was raised thinking that one must disconnect the speaker from the poet when talking about poetry—please understand that its use here is as much an evacuation as any of the poems in the book.)

Imagine waking up in the grass, in the process of being examined by a rabbit who recognizes you as an interloper, so alien that you should really “be making pancakes on the moon,” as in “Sleeping outside the Kelowna bus station” (p. 18). The interloper wants to forge a connection with the animal but is overwhelmed by a complicated, violent family history with rabbits. They wish they could “get him/a ticket in the morning to come with” but understand that they can’t, that the rabbit has a community and a role. The speaker wants to connect but is unable to.

Throughout Walsh’s poetry, nothing is fixed and we are perpetually discovering truths or hiding them. Safety is often contingent on disguise; when the speaker ruminates on their father’s love, in “I think my dad liked me” (p. 46), it is based on assumptions and hearsay, which the speaker keeps a catalogue of:

I think my dad liked me because I was good at pretending

I wanted a Pamela Anderson poster in my room.I think my dad liked me because he didn’t know that what I wanted was to be

Pamela Anderson in the red bathing suit, circa Baywatch theme song credits.

In fact, the speaker relates to and assembles themself out of various characters from popular culture. Perhaps the most striking self that the speaker sees reflected back is the character, Cringer, from the 1980’s cartoon, He-Man and the Masters of the Universe. In the show, Prince Adam calls upon the power of Greyskull to transform both himself and his pet tiger, Cringer, into the superheroes He-Man and Battle Cat. Cringer is a trembling “scaredy cat” who’s afraid of his own shadow. Yet in Battle Cat we see a fearsome and strong beast. But the speaker sees both personas at the same time as they overlap one another, and in this observation seems to reveal the liminality of their own identity. By the same token, in choosing to base their “entire masculinity” on Cringer, the speaker gloriously elevates and legitimizes the queer anxiety that propels us through the book. While super-heroic transformations are often about wish fulfillment, Cringer cowers at the thought of becoming Battle Cat, often going so far as to plead with Prince Adam not to call upon the power of Greyskull to transform them. Cringer is perpetually afraid. He would rather hide or escape than deal with difficult situations. Yet Cringer is also Battle Cat, able to put on the mask and transform into He-man’s fearsome sidekick. The speaker aligning themself with Cringer is a rejection of traditional masculinity, or a redefining of it, undermining it even when it is thrust upon them by other people’s assumptions.

That anxiety, exemplified by Cringer, is omnipresent, and when they choose to reveal themself—as in coming out to their mother in “Individual cats” (p. 19)—they also choose to do so in spaces that facilitate escape, like the Superstore parking lot. We are told about the coming out but not shown it, the moment elided as we leap from anxiety to “But my mom is so good about everything now…”.

Never linger, never dwell. Love and safety are conditional; it is better to move quickly through a space rather than be nailed down and destroyed. Even the space that the speaker is moving through is changing and uncertain. “I’m told that space is expanding but I don’t know/what that means for me personally” (“Tree of Mars,” p. 66), they say.

But how does all of this make you feel? Sometimes writing a review can feel liminal too, like trying to both describe and disguise how you feel. While Walsh’s speaker moves through space, they’re still reaching out to us; the voice is intimate and exposed, each poem revealing something in hopes that we will hold on, that we will come with them or hold them close. Walsh’s poems are a whisper between potential lovers, potential friends, potential everything. It isn’t about imbuing them with the Power of Greyskull. It’s about standing with them in the grass outside of a bus station in Kelowna, or in the parking lot of the Superstore. They want us to reach out and close that space.