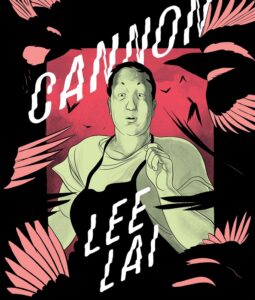

Lee Lai, Cannon (Drawn & Quarterly, 2025), 300 pp., $39.95.

As a freelance reviewer and compulsive reader for nearly four decades, I can say honestly that Lee Lai’s Cannon is not only one of the best graphic novels I’ve read, but one of the best books, full stop. I’ve read it three times now, each encounter deepening my connection to the story Lai is telling and my appreciation for their ability to draw me into this extraordinary work. It took me back to the experience of reading my first graphic novel, Art Spiegelman’s Maus in 1991, which I couldn’t put down and which still thrills me on every rereading. Cannon has, in its very different way, the same kind of power.

Lai plunges readers immediately into a seven-page opening sequence that sets the tone for the novel: first, a quietly uncanny full-page image of magpies surveying a scene of bedlam, followed by page after page of chaos—broken tables and chairs, smashed plates and glasses (beautifully echoed in the book’s endpapers), cutlery scattered everywhere. What’s happened? Where are we? Then Lai introduces the two central characters, with filmic precision: one struggling to breathe, the other more composed, gradually taking charge while infusing the scene with a dark humour that deepens as we move further into this astonishing book.

Lai is a queer, trans, mixed-race cartoonist whose work is marked by a distinctive minimalist style and an exceptional command of visual storytelling. Their drawings—clean lines, expressive bodies, carefully controlled colour—do enormous emotional work. In Cannon, that precision is put to devastating use.

Set during a suffocating heatwave in Montreal in the summer of 2017, Cannon explores the friendship between Lucy, known as Cannon, and her longtime best friend Trish. The two have been friends for fourteen years, but something in the relationship is no longer holding. Cannon, the novel’s emotional centre, is anything but a “loose cannon,” despite the nickname Trish jokingly gives her.

Cannon’s life is crowded with strain. She is the only woman working in a hectic bistro, where her boss, Guy, is a manipulative presence who pits staff against one another and repeatedly hits on her. She also bears responsibility for her aging grandfather, Gung gung, whose health is failing, because her mother, who is an absent presence in her life, as we see throughout the graphic, can’t.

There is also Charlotte, a new hostess at the restaurant who may be interested in a relationship, though Cannon proceeds cautiously. And then there’s Trish, an up-and-coming writer, also Chinese Canadian, who jokes that she and Cannon were the only two queer, English-speaking Asian Canadians in Lennoxville, the Montreal suburb where they grew up..

Trish, reeling from a recent breakup, drifts through casual sex and creative frustration, struggling to find the right subject for her next project. Although Cannon and Trish share a long history, Trish increasingly talks over Cannon, paying little attention to the pressures her friend is under and failing to recognize how abandoned Cannon feels.

Cannon, for her part, doesn’t speak up, which only compounds the problem. She tries to cope by jogging and listening to New Age relaxation tapes, but nothing seems to help. Lai makes this stress viscerally visible, peppering panels with magpies that only Cannon can see.

Throughout the novel, Lai moves fluidly between storylines using an array of techniques—black pen-and-ink panels give way to sudden washes of crimson; overlapping dialogue bubbles conveying how characters speak over Cannon; half-visible sentences capturing the noise and distraction of restaurant life. As readers, we can see that Cannon is nearing a breaking point long before anyone else does.

That breaking point arrives as pressures converge. Cannon discovers that Trish is using Cannon’s life as material for her writing. She suffers panic attacks at work. She sees Charlotte flirting with Guy. Her grandfather collapses and is hospitalized. During a particularly brutal night at the bistro—Grand Prix season in Montreal—Guy makes a pass at Cannon and, when she rejects him, insinuates a threat. It is almost too much.

Trish, meanwhile, slowly realizes her friendship with Cannon is in jeopardy. On the night Guy finally pushes Cannon too far, Trish comes to the restaurant hoping Cannon will open up. And that’s when everything finally snaps.

In a stunning sequence that shifts abruptly from three pages of black-and-white panels to four pages in the crimson tones associated with horror films Cannon and Trish watch together throughout the graphic, the pair destroy the restaurant, ending in a pair of full-page crimson illustrations. The story has come full circle, returning us to the opening sequence. It is magnificent.

Lai resists tidy resolution. The novel does not wrap everything up neatly, but it does suggest that Cannon and Trish have difficult work ahead if their friendship is to survive—and that Cannon can no longer afford to bottle everything up.

There is far more to say about the power of Cannon: how sensitively Lai depicts queerness; the way they draw naked bodies and sexuality with tenderness, variety, and care; how deeply the book understands the stress of not being heard. Lai does not judge their characters or ask them to be perfect—only human.

What struck me most, however, was how cinematic the experience of reading Cannon feels. There are clear nods to horror films—Carrie most obviously, with echoes of The Birds in the recurring magpies—but there is also an implied soundtrack and a filmic use of close-ups, quick cuts, panning shots, and visual “voiceovers.” The panels function like movie stills. Lai has described thinking of panels as a camera lens, favouring a dialogue-driven, “show don’t tell” approach that creates enormous emotional pressure within each scene.

Cannon is, quite simply, breathtaking. Lai’s ability to make their characters feel utterly alive is mesmerizing, and the tenderness with which queerness is rendered feels rare and deeply affirming. As a queer reader, I felt seen—not because the book insists on difference, but because it so generously attends to what makes us human, flaws and all. I can’t wait to see what Lee Lai does next.

Jeffrey Canton began his freelance career interviewing queer writer Patrick Roscoe for Xtra! in 1990, writing features on LGBTQ2S+ creators including Makeda Silvera, Timothy Findley, Jeanette Winterson, Peter McGehee, and Doug Wilson, and later writing the newspaper’s “Between the Covers” column. He’s currently the Children’s Books columnist for The Globe and Mail.

Jeffrey Canton began his freelance career interviewing queer writer Patrick Roscoe for Xtra! in 1990, writing features on LGBTQ2S+ creators including Makeda Silvera, Timothy Findley, Jeanette Winterson, Peter McGehee, and Doug Wilson, and later writing the newspaper’s “Between the Covers” column. He’s currently the Children’s Books columnist for The Globe and Mail.