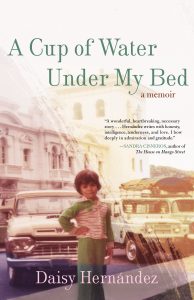

A sprawling, expansive memoir that spans two continents and bridges different worlds in the process, Daisy Hernández’s A Cup of Water under My Bed revels in the complexities and the chaos of the queer immigrant experience. This is a book that refuses easy answers and complicates straightforward, homonationalist understandings of queerness.

Hernández writes with grace and clarity about the ways in which her experiences of migration and poverty as a racial and linguistic outsider have shaped her sexuality and queerness. One of the strangest aspects of the ways in which queerness is spoken about in public discourse today is how completely sexuality and sexual identity have been divorced from all other kinds of experiences and forms of identification. It’s almost as if we are taught to believe that it is possible to understand the queer experience simply by looking at sexuality itself—that other kinds of experiences couldn’t possibly inform or have anything to do with one’s sexuality. Hernández turns this bleached notion of sexuality on its head; there is no way to understand her sexuality without also coming to grips with the other experiences that have shaped her: her migration, her poverty, her gender, spirituality, her elders, etc. This makes for a far richer and more rewarding reading experience.

Hernández spends a good amount of time sketching the alternately comic and tragic experiences of being a Colombian newcomer in New Jersey: tales of alienation are punctured with hilarious anecdotes of difference lost in translation. She writes eloquently of the beginnings of resentment towards the Spanish language, how the xenophobia and racism she experienced out in the world were refracted back onto her parents, how it was easier to blame them for being too Spanish, too new, too other than to blame the racists and xenophobes for being racists and xenophobes.

While officially Catholic, her parents have brought with them ancient spiritual practices that remain somewhat hidden and obscure to Hernández as a child. One of the most beautiful aspects of this memoir is the way it gives new life to what are considered pagan or “dead” spiritual practices (“brujas,” in today’s queer chicana lexicon). Growing up, Hernández goes to Catholic church every Sunday. Her father, however, does not, choosing instead to commune with a candy dish in the basement. Eventually Hernández makes the connection between his spiritual practice and the official religion being given to her: “When the white men arrived in Africa, they failed to see the gods. They beat the Yorubans, shoved them onto ships, across the oceans, and never suspected that the holy ones were heading for the Americas—the Yorubans drummed and danced and sang, the spirits came down and took hold of their heads and wrists and feet—the Spaniards forbade their practice of the religion.” She begins to trace the ways that colonialism has shaped these (forcibly hidden) spiritual practices:

It began like this perhaps: The saint in public and the orisha in secret. The bleeding Jesus in the living room and Elegguá in the basement. And high above our heads, the tin rooster my mother keeps above the kitchen cupboard: Osun, the one who brings messages when your life is in danger.

These practices might seem marginal or inconsequential but come to have considerable importance later in life, and they shape Hernández’s psyche in particular and particularized ways. They also give rise to the title of this book: a cup of water is placed under the bed to protect the sleeper from evil spirits. Later, Hernández writes hilariously about visiting a “psychic” with her mom on Bergenline Avenue in Jersey, an experience she can’t quite make sense of as a child but the significance of which she comes to understand later in life:

Sometimes now when I think about the women my mother called on, I consider how they may have helped her to feel less alone in this world. At least there was a woman to talk to, to ask questions of, to sit with, because no one ever mentions the silence that follows the painful moments. Everyone talks of what happened when the forelady announced the factory was closing, when a man beat a child and the police were called, when a girl realized that going to college would cost thousands of dollars. But of what happens afterwards, no one ever speaks.

It is an empty room, that afterwards, a soledad, and it sits there at the center of a person’s life and waits to be filled.

This is a memoir that doesn’t even mention sexuality or desire in any substantial way until about halfway through the text. This is one of its greatest strengths. Reading this memoir, one can’t help but wonder if a normative, cis, middle-class white gay or lesbian could find anything in here that would resonate with their own experience. Perhaps the importance of this text lies in the fact that there isn’t much—that it speaks to experiences and identifications that almost always remain unspoken or forcibly hidden in mainstream queer discourse. Hernández’s memoir fills in these elisions and shows how much queer complexity still remains to be revealed.

Daisy Hernández, A Cup of Water under My Bed (Beacon Press, 2014), Paperback, 181pp, $22.00

Asam Ahmad is a poor, working-class writer, poet, and community organizer. His writing tackles issues of power, race, queerness, masculinity, and trauma. His writing and poetry have appeared in CounterPunch, Black Girl Dangerous, Briarpatch, Youngist and Colorlines. His poem “Remembering How to Grieve” can be found in Killing Trayvons: An Anthology of American Violence.