BY RACHNA CONTRACTOR

Last year Arsenal Pulp Press published Vivek Shraya’s first novel, She of the Mountains, which elegantly juxtaposes two love stories, one based in Hindu mythology and one loosely based on Shraya’s life. With only two main characters and a handful of secondary characters, the story maintains a clarity that allows for nuance to come through in the writing—this is a book that makes you feel before it makes you think.

The main story is simple: he grows up experiencing homophobia in Edmonton; he falls in love with her. They separate. He dates Smith briefly. He and she get back together. They move to Toronto. They tussle with each other while remaining intensely connected. They separate again. Yet in only 147 pages the narrative is so layered and poetically written that we can see all of him; his desires, insecurities, and self-destruction are vividly brought to life.

Shraya’s conscious decision not to name the two main characters was intended to keep them relatable, as constructs of the reader’s imagination, perhaps allowing readers to insert themselves into the story. However, the use of he and she—third-person pronouns—maintains a distance between the character and reader, preventing a closeness which comes from knowing someone’s name. It’s the only disappointment I felt from a book that gives so much. By naming him Smith, Shraya tells us that his short-term boyfriend is based on every generic, white, gay guy that everyone knows.

Writing in the first person, Shraya has succeeded at retelling a feminist interpretation of one of Parvati’s stories. Through space and time, the human world, and the realm of Gods and Goddesses, she is in control of her love and longing for Shiv. They are accompanied by their sons Ganesh and Muruga, who in a traditional retelling may appear at the forefront.

There are several contemporary queer South Asian authors who incorporate Hindu mythology into their fiction: Manil Suri, Devdutt Pattanaik, Karishma Kripalani. This is not a coincidence. When asked about this Shraya said, “Hinduism is a queer person’s playground, Hindu Gods were my first queer role models.” Hindu mythology features characters who are unlike each other—Ganesh has the head of an elephant, Shiv is often blue in colour, Kali has anywhere between four and ten arms—set in stories that have been interpreted in as many ways as there are Hindus. To many, Hinduism is a religion based in thought and freedom, expressed through mythology, which enables its believers, and in Shraya’s case those raised in the religion, to take agency and retell those stories as their own.

Shraya’s gender-bending, feminist reinterpretation of Parvati’s various loves and lives colludes with his story to gently question our ideas about queerness. Who defines queer? Who polices the use of language; words like queer, gay, bi? In these stories we are presented with the grey zone, which is more vague. He loves without the limitation of language and labels, which presents more possibilities for acceptance.

As much as love, this book is about the body, embodiment; the ways that we respond to, reject, love, and hate ourselves. The novel explores homophobia, fatness, and whiteness, and how they act out on the body, how we act otherness out on each other. Visceral desire and memory are central to his narrative, coming to terms with self-resentment and moving towards self-acceptance. The two stories cycle around creation, destruction, re-generation; never-endings.

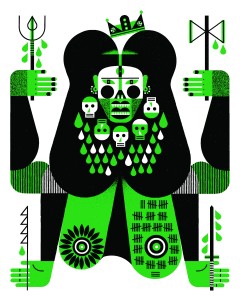

As with all of his projects, Shraya has put a lot of thought into every detail, including the book’s look and feel. The arrangement of words on the page in certain passages is as important in telling the story as the words themselves. One whole page is full of “you’re gay” repeated line by line, in various sizes, punching you in the gut, driving the point home. The two stories—Parvati’s and theirs—are glued together by Raymond Biesinger’s minimalist illustrations, an element rarely used in fiction. Unlike in many traditional mythological depictions, Biesinger has illustrated Parvati alone, without father, husband, or son, asserting her as central in this retelling.

Shraya’s talent as a writer shines through in his use of descriptive imagery. His paragraphs are beautifully written, each like a standalone story. Like many epic stories from Hindu mythology, She of the Mountains is a timeless love story about two people drawn together by something larger than themselves, yet kept apart by each other. Vivek Shraya received his third Lambda nomination for She of the Mountains in the category of Best Bisexual Fiction.

Vivek Shraya, She of the Mountains (Arsenal Pulp Press, 2014). Paperback, 147 pp., $18.95

Rachna Contractor writes about art, community and social change.