by Michael Walter

Can the internet free us from Canada’s history of censorship?

The Canadian government hasn’t always been the biggest protector of free speech. Sure, things have improved a lot in recent years; we’ve gradually seen the growth of an open public space where queer literature has made some headway, and the Internet continues to break down barriers and let marginalized people have more of a voice. But the long history of Canadian censorship and control of the publishing industry still has a huge impact on the literary landscape, especially for LGBTTQI writers and readers. By taking a closer look at the history of censorship in Canada, we can get a better understanding of the forces working to marginalize LGBTTQI literature today, and we can get an idea of what the future of queer publishing might look like.

In there past there have been two main forms of censorship in Canada: direct censorship by the government, backed up by laws, the police and Canada Customs, and indirect censorship through social structures, advocacy groups and other, less formal, means of control.

Direct censorship is the most familiar form by far. In the 20th century, if you published something the Canadian government didn’t like, you didn’t have much hope of getting anyone to read it. If you tried to import books, they could be seized by customs agents. If you tried to transport books to bookstores, they could be seized by the postal service. And of course, the most direct threat: as the publisher, you could be prosecuted under the criminal code and fined or imprisoned.

The standard the government used to test if your book was moral enough for upstanding Canadians to read was called the Hicklin test (it comes from an 1868 English obscenity trial). A publication would fail the test if it was determined to “deprave and corrupt those whose minds are open to such immoral influences.”

How could something so archaic be used in the 20th century?

If this sounds a little outdated, even irrelevant, bear in mind that the same standard was used by the federal government up to the 1960s, and for many years afterwards by the provinces.

If this sounds a little outdated, even irrelevant, bear in mind that the same standard was used by the federal government up to the 1960s, and for many years afterwards by the provinces.

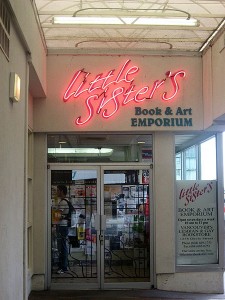

Canada Customs seized books for decades, arbitrarily confiscating publications they decided were obscene, particularly if the books in question were being sent to a bookstore or distributer that catered to the LGBTTQI community. In a famous example, a shipment of Jane Rule’s novel The Young In One Another’s Arms en route to Little Sister’s bookstore in Vancouver was confiscated by customs agents in 1990 (the novel deals with lesbian themes). It seemed to make no difference that the book had been sold regularly in Canada for the previous thirteen years. (“Downtown Canada: Writing Canadian Cities” by Justin D. Edwards and Douglas Ivison, pp.84-85)

In 2000, the Supreme Court of Canada criticized customs agents for a pattern of unfairly targeting books shipped to LGBTTQI stores, but, crucially, agreed they had the legal power to seize anything that sufficiently offended their sensibilities.

This is all troubling, but probably won’t come as a huge surprise to many Canadians. But there’s a much more disturbing trend of censorship in Canada that was used for decades to exclude minority voices from public spaces altogether.

How does technology challenge censorship?

The type of censorship we’ve discussed so far was designed in an era where books were expensive, difficult to produce, and manufactured and sold by a small number of companies. Before World War II, publishing and printing books was a capital-intensive industry. There were few bookstores and they carried a limited number of volumes, all hardbacks. In 1953, a Senate committee tasked to “examine into the sale and distribution of salacious and indecent literature” estimated that in the few years prior, the number of bookstores government censors had to police was as low as 200. (Journals of the Senate of Canada Volume 97, pp. 386-387)

But in the mid-20th century, the economics of publishing changed radically with the technological advances during and following the war. Suddenly there was a new form factor for books—the paperback—that required less investment and was much cheaper and quicker to make. The Senate committee bemoaned the new “soft-covered book, selling at a small price.” Suddenly, thousands of new novels, books, magazines, periodicals and comics were being published. New, less formal stores sprang up (what the committee called “display stands”) to sell all this new material. The number of book-selling institutions went from around 200 to over 9000 in a few years. The committee’s report is full of appalled horror at the scale and overwhelming “efficiency” of these new means of production and distribution and the possible effects these new books might have on the “high school and early university students” of Canada.

At the same time, a huge increase in international trade made it much harder for Canada Customs to weed out scandalous books before they made it into the country. The committee warned that the “facilities and machinery of the Customs and Excise Division” were “absolutely inadequate” to defend innocent Canadian children from the horrific perils of foreign obscenity. It’s even tempting to think that Canada Customs’ long-running discrimination against LGBTTQI book vendors might be based on nothing more than convenience, singling out books based on their destination rather than trying to judge the moral rectitude of tens of thousands of books each year.

This explosion in the number of books the government had to deal with each year totally overwhelmed their capacity for censorship. Customs offices were flooded. Crown Attorneys were inundated with calls to suppress salacious books, pamphlets and magazines. Even the threat of a conviction for publishing obscene material became less effective; in the past, banning a book would take it out of circulation for years or decades. Once there were hundreds of cheap presses, a new edition with a few minor edits could be printed within weeks. To put it simply, direct government censorship didn’t scale well as technology changed the way people published books.

Does new technology bring about social change?

Predictably, not everyone in Canadian society viewed this change as the beginning of a new era of choice and affordability. To quell the moral panic, pressure groups lobbied politicians to do something—anything—to keep objectionable books out of the hands of their children, partners and fellow citizens.

Some provinces solved the problem by forming “advisory boards”. A panel of citizens would review a publisher’s literature before it was published and let the company know if they were offended, shocked or otherwise appalled by any texts. The members of the panels were sometimes citizens qualified by profession (e.g. literature professors, journalists, teachers) but just as often were members of the very same social and religious advocacy groups whose outcries had convinced provincial governments of the need for such panels in the first place.

Because the decisions of these boards didn’t have any real weight in law, they were able to deal with the increased volume of literature that was flooding Canada. Government censors were burdened by regulations, legislation and the possibility of a public appeal, so had to give each book at least a cursory examination and base their decisions on some kind of evidence. But advisory panels didn’t have to bother with such formalities because, after all, they were just members of the public expressing their opinions. Their rulings could be based on any reason, or none, with no real accountability, so they had no trouble judging literally thousands of books.

The problem with the system was that boards like those formed in Alberta (the Alberta Advisory Board on Objectionable Publications, 1954) and Ontario (the Ontario Attorney General’s Obscene Literature Committee, 1960) were convened under the direction of the provincial government. They could plausibly claim that their decisions were non-binding, but in reality publishers got a virtual guarantee from local authorities that, if they followed the rulings of the boards to the letter, nothing they published would be censored and they would be at no risk of prosecution for publishing obscenity.

Why did people accept this kind of censorship?

Perhaps surprisingly, publishers loved this system. The prize of being protected against the expense and embarrassment of a public obscenity trial was well worth the small inconvenience of not being able to publish a certain percentage of their catalogue.

The real beauty of the system was that the advisory boards could (and did) describe themselves very positively, even saying they were “anti-censorship” organizations that helped publishers avoid accidentally publishing something indecent. (After all, surely no respectable publisher would intentionally print something that might offend the public.)

Even more fortuitously, because censored material was removed before it was ever published, provincial governments soon realized that they could avoid the scandal of obscenity trials themselves. Crown Attorneys dreaded the prospect of describing a book’s salacious details to a crowded courtroom full of red faces and knowing smirks. (Predictably, it was very common for a book’s sales to skyrocket during the course of such a trial—a pre-internet version of the Streisand Effect.)

The result was a comprehensive system of censorship. Publishers accepted the rulings of the boards or faced the implicit threat of prosecution, and a handful of citizens decided what was acceptable for the rest of the province to read. Rather than getting a trial, a verdict and a chance to appeal, a writer who didn’t pass muster with an advisory board would be silently dropped by their publisher and the public would hear nothing about it.

And just what did it take to “deprave and corrupt those whose minds are open to such immoral influences”? Virtually anything that challenged the social orthodoxy of the time was fair game. Inexorably, LGBTTQI voices were suppressed, silenced, wiped from existence, all without the trivial inconvenience of a public trial. In fact, as they became less common, the threat of an obscenity trial seemed to grow more intense. Many publishers of the time would withdraw a book or magazine at just the threat of a lawsuit. One publisher in Nova Scotia withdrew material province-wide at the demands of a single preacher.

Are we free from the legacy of censorship?

Thankfully, the power of censorship has declined since its heyday. In the 1960s, the legal definition of obscenity changed and for the first time publishers could use the artistic merit of a book as a defence against a charge of indecency. Over the next decade, this new standard gradually filtered down to various arms of censorship enforcement, but well into the 1970s some advisory boards were using the old rules. The 1982 Charter of Rights and Freedoms strengthened freedom of speech law, and gradually most of the apparatus of censorship (with the notable exception of the ongoing activity of Canada Customs) was dismantled. But even though there’s a clear trend towards literary freedom, publishers continue to censor themselves. Most often, minority voices are the targets.

LGBTTQI bookstores and publishers have made such astounding progress in the past decades that it can be easy to overlook how poorly some mainstream publishers and literary agencies treat queer literature. Examples aren’t hard to find: author Jessica Verday was told a short story couldn’t be included in an anthology because it included a gay relationship; Sherwood Smith and Rachel Brown were offered a deal by an agent on the condition that they change or omit the sexual orientation of a gay character; Brent Hartinger was told by agents and editors to abandon his novel Geography Club–not on its merits, but because there was “no market” for a young-adult book about gay characters; a Publisher’s Weekly article reports authors’ fears of being “blacklisted” if they publicly reveal the pressure they experience from editors and agents to change the sexual orientation of their characters.

It’s hard to pin down where this kind of discrimination comes from. It’s possible that some publishers and agencies are simply harbouring explicit prejudices. But it’s equally possible that, just as with publishers’ collaboration with advisory boards in the past, this discrimination is the result of commercial pressure to take the path of least resistance. For LGBTTQI writers, at least, the reason doesn’t matter that much—a refusal to publish is a refusal to publish any way you look at it.

That’s not to say mainstream presses are the only option for queer writers.

There’s a passionate, rich and diverse community of publishers that has emerged to embrace queer literature, and it’s made huge headway into making queer lit widely available. But the economic climate has been hard on the industry, as it has been for all specialist publishers, and LGBTTQI presses can only accept so many books per year.

Can technology free us once again?

One of the most exciting developments in publishing is the rise of new distribution channels: ebooks on electronic readers and cheap, high-quality print-on-demand paperbacks. At first glance, these channels seem perfect for writers whose work may be marginalized at mainstream publishing houses: they’re relatively cheap to set up, they can (in theory) reach a virtually unlimited audience, they can scale limitlessly with demand and, compared with traditional publishing, they’re subject to virtually no forms of censorship or other types of control over content. In the same way the Internet itself has proved an invaluable tool for discussing and increasing awareness of LGBTTQI issues, these new publishing paradigms have the potential to radically change the publishing landscape for queer writers.

But self-publishing—even shiny, 21st century self-publishing—has severe drawbacks. Where traditional queer publishing has been supported by the close-knit and active LGBTTQI community, it’s much harder for queer writers who self publish to reach out to this audience, and harder still to reach the public at large. A typical self-publishing writer doesn’t have a large marketing budget and often has few contacts or professional relationships. And that’s not even addressing the mammoth task of actually finishing a book without help editing, formatting, typesetting, error-checking and finding cover art.

Allowing authors to self-publish isn’t the only way these new distribution channels can affect the future. Already, some small publishers are leveraging the enterprise-level ebook, print-on-demand and distribution services available online from industry giants like Amazon and Ingram. These kinds of measures aren’t going to level the playing field between micro-presses and the publishing “big six”, but they do allow niche presses to scale production to demand in a way that was impossible even ten years ago. This kind of technology has the potential to answer some of the logistical and economic challenges of running a small publishing company. The future is uncertain but exciting.

But there’s a final challenge to the widespread proliferation of LGBTTQI literature: not censorship, but the tastes of the public itself. New technology is opening up publishing to more competition from all sides, but it’s also creating a more laissez-faire market for books than there has ever been. The positive side of this kind of marketplace is more freedom from censorship, lower barriers to entry for writers and a more diverse range of literature for the public. But the negative side is that the tastes of the public will be met more directly, crudely and cheaply than in the past. The first generation of books published through these new technologies has already been released, and some of the first to cross over to international success exhibit the worst of gender roles, heteronormativity and other unpleasant social mores. Just as literature has the power to examine, critique and change social values, so too do social values influence the literature that rises to the forefront of public awareness in a market free of editorial controls.

It’s churlish of me to complain about the tastes of the public when clearly, once you get rid of censorship, people will write books to match what other people want to read. Trashy books that become popular don’t somehow corrupt the public; they just reveal public tastes. Here’s hoping that those same tastes can be challenged by books from a range of voices that use freedom from censorship to startle, question and amaze.

Michael Walter is a literature student at University of Toronto, a technology buff and an occasional freelance writer. He chiefly writes about new trends in publishing and digital distribution. He also has a blog about love poetry.