H. Nigel Thomas, A Different Hurricane (Dundurn Press, 2025), 250pp., $25.99.

On a quiet morning in 2017, the island of St. Vincent seems utterly calm. Yet, for Gordon Wiley, there is turbulence—for reasons the reader will soon discern. A thick backstory unfolds in flashbacks and sequences from his dead wife’s secret journal; these elements make for an intriguing plot about the authentic self in relation to hidden sexual identity. Since Maureen’s death from AIDS a year ago (a disease she contracted from him), Gordon fears what their daughter Frida (named after the feminist Mexican painter) will discover when she arrives.

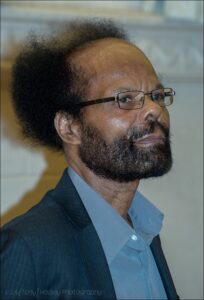

Caribbean-born H. Nigel Thomas (an award-winning gay writer who lives and works in Montreal) continues his career-long exploration of gay characters and themes in this intergenerational saga. As he has remarked to freelance journalist Irwin Rappaport, A Different Hurricane is his most personal novel, a product of memories that have haunted him since his days as a young queer in St Vincent and the Grenadines. A potent part of its plot targets the life-threatening risks to LGBTQ communities across the Caribbean, with an especially damning portrayal of Vincentian life and mores. Serving at times as the novelist’s mouthpiece, Maureen notes in her private journal, “There’s not much to do in St Vincent beyond going to the beach and eating and visiting friends and colleagues. Here only students read. At home people mostly listen to music or watch rented films. Of course, for most uneducated Vincentian men, life is work—if they have a job—getting drunk, playing cards, and wenching.” Her journal, which constitutes a large part of the novel, is a significant framing device, marked by her striving to tell the hidden truth—while keeping that same truth from daughter Frida who, not surprisingly, is neurotically virginal, though intellectually brilliant.

What drives this retrospective novel is Gordon’s double life, begun in boyhood when he fell in love with Allan, a neighbourhood boy of stronger intellect, in a place where gays were mocked and called “woman-man, antipympym, and buller.” Their love affair lasts twelve years. Allan grows up to be an atheistic doctor and remains a loyal friend to Gordon, even though they are threatened with physical harm and moral shame by their community’s widespread homophobia. While Allan is also married, the parameters of his marriage are different from Gordon’s: he does not contract sexual disease or infect his wife, Beth, and she does not consider his homosexual affairs to be as grievous as heterosexual infidelity. On the other hand, Gordon’s marriage to Maureen (whom he impregnated outside wedlock) is a different masquerade, a union without any mutual sexual passion. Brought up by a cold, Methodist mother with wisdom “forged in the kiln of cynicism,” and a father who abandoned wife and daughter, Maureen is well-read and she realizes she herself has been a willing part of the charade by lying about Gordon’s artificial, public self. Once nicknamed Sister Goody-Goody by convent classmates, she is dying of AIDS. Maureen also knows, from a course in Jungian psychology, that there will be hell to pay if their false selves overwhelm and swallow up their true ones.

What drives this retrospective novel is Gordon’s double life, begun in boyhood when he fell in love with Allan, a neighbourhood boy of stronger intellect, in a place where gays were mocked and called “woman-man, antipympym, and buller.” Their love affair lasts twelve years. Allan grows up to be an atheistic doctor and remains a loyal friend to Gordon, even though they are threatened with physical harm and moral shame by their community’s widespread homophobia. While Allan is also married, the parameters of his marriage are different from Gordon’s: he does not contract sexual disease or infect his wife, Beth, and she does not consider his homosexual affairs to be as grievous as heterosexual infidelity. On the other hand, Gordon’s marriage to Maureen (whom he impregnated outside wedlock) is a different masquerade, a union without any mutual sexual passion. Brought up by a cold, Methodist mother with wisdom “forged in the kiln of cynicism,” and a father who abandoned wife and daughter, Maureen is well-read and she realizes she herself has been a willing part of the charade by lying about Gordon’s artificial, public self. Once nicknamed Sister Goody-Goody by convent classmates, she is dying of AIDS. Maureen also knows, from a course in Jungian psychology, that there will be hell to pay if their false selves overwhelm and swallow up their true ones.

Thomas makes fine use of local dialect (particularly in the mouth of drunken Freckles, a loud, wife-battering cocksman) and multiple points of view (including stream of consciousness), but he doesn’t altogether avoid editorial intervention. His story’s real fascination and power lie in its insights into the complexities of queer love. Little wonder there is a reference to Brokeback Mountain, that film which evokes the tender melancholy and heartbreak of a doomed queer relationship, one rooted in a loneliness not simply sexual, but also existential. Thomas’s novel is tender and painful, too, but much too demure in its treatment of gay sex. Thomas has none of the lewd raunchiness of Larry Kramer, the fantastical perversities of William S. Burroughs, or the sexual ecstasies of Edmund White; nor does he demonstrate the stylish grace of an Andrew Holleran, or the satiric wit of an Andrew Sean Greer. His sex scenes are almost self-apologetic, their most vivid markers being spontaneous tumescence and a furtive touch or kiss. Graphic queer love is pushed into the background, as if real-life homophobia and submerged guilt had something to do with this literary restraint or constraint. But isn’t a dimension at the heart of queer love a deep yearning to have a safe space: not so much for queer sex as for a self that is threatened by a society that refuses to accept radical psychological difference? Despite a final flurry of anger and recrimination, violence and resignation, all the drama shrinks into something far less than some of its parts, along with Thomas’s metaphor of a psychosexual hurricane.

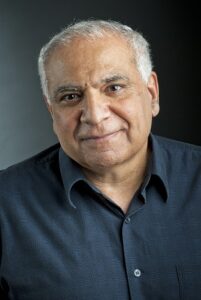

Keith Garebian of Mississauga has won international acclaim for his books on theatre (especially his Broadway production histories and his biography William Hutt: Soldier Actor). He has also been widely praised for his poetry collections Frida: Paint Me as a Volcano (Buschek), Blue: The Derek Jarman Poems (Signature), Children of Ararat (Frontenac), Poetry is Blood (Guernica), Against Forgetting (Frontenac), In the Bowl of My Eye (Mawenzi House), and Finger to Finger (Frontenac). Some of his poetry has been translated into French, Romanian, Bulgarian, Hebrew, Hungarian, and Armenian. His latest gay poetry collection, Stay (JLRB Press), was recently reviewed in Plenitude.

Keith Garebian of Mississauga has won international acclaim for his books on theatre (especially his Broadway production histories and his biography William Hutt: Soldier Actor). He has also been widely praised for his poetry collections Frida: Paint Me as a Volcano (Buschek), Blue: The Derek Jarman Poems (Signature), Children of Ararat (Frontenac), Poetry is Blood (Guernica), Against Forgetting (Frontenac), In the Bowl of My Eye (Mawenzi House), and Finger to Finger (Frontenac). Some of his poetry has been translated into French, Romanian, Bulgarian, Hebrew, Hungarian, and Armenian. His latest gay poetry collection, Stay (JLRB Press), was recently reviewed in Plenitude.