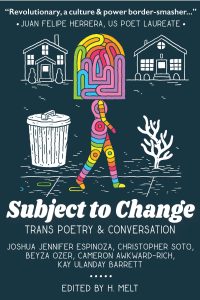

I read Subject to Change: Trans Poetry and Conversation, edited by H. Melt, while on a train going to a conference. Not only did nearly all of these poems mention the restlessness that travel provokes, making it the perfect companion, but the work of these five trans poets (Joshua Jennifer Espinoza, Christopher Soto, beyza ozer, Cameron Awkward-Rich, and Kay Ulanday Barrett) helped me to synthesize a particular experience I tend to have when I leave the trans community and engage with the broader academic world. Instead of talking to me about trans issues, people throw bad poetry at me.

After presenting my work on trans and nonbinary writing, someone said what I was doing was “brave.” At other conferences, people have told me that trans identity is fascinating because it is so liminal; or transformative; or so much like a phoenix rising from the ashes; or something else equally patronizing without necessarily meaning to be. Most gender scholars would say that these lines are transphobic micro-aggressions—but after reading Subject to Change, I much prefer to think of it as bad poetry. These answers don’t engage with trans people—they engage with metaphor, analogies, and tropes because for so long, trans people have been the symbol in stories and poetry, rather than the writers of them.

I didn’t quite put this all together so succinctly, though, until I read Cameron Awkward-Rich’s poem “Essay on the Theory of Motion.” In one of the last stanzas, he delivers these utterly cutting tongue-in-cheek lines:

Get it? Gender is a country, a field of signifying

roses you can walk through, or wear tucked

behind your ear.

Eventually the flower wilts & you can pick

another, or burn the field, or turn & run back

across the tracks.

In this poem, Awkward-Rich attempts to deconstruct the done-to-death analogy of trans narrative as travel story, and does so by directly calling it out. His “Get it?” is the pattern articulated by cis people who consistently see the body of a trans person as a neat poetic trick and not a lived reality. The “Get it?” is also a directcitation of bad writing itself, overused and obvious. The “Get it?” breaks the veil of poetry-as-art and makes poetry become resistance.

Each one of the five authors in this collection takes the typical artistic assumptions of what we want poetry to do and inverts it, while also rearranging entirely the political expectations for trans people. This is not a collection of writing and poetry from trans authors, interspersed with conversations about identity and experience; it is, as Melt says in the introduction of Subject to Change, a place where the seemingly disparate identities of trans person and poet meet and flourish, while also allowing other identities and intersectionalities the space to speak freely.

In Joshua Jennifer Espinoza’s final line of “Poem (Let Us Live),” she questions whether or not what she’s writing is even a poem, rather than her “begging you / to let us live.” Christopher Soto’s work does much the same in testing the boundaries of the poetic form. Though he worries that his lines are not as cohesive as those of some of his contemporaries, h

is work is sporadic while also adhering to a narrative that comes together in a rather clever way. In his “Home (Chaos Theory)” he questions the notion of “‘homelessness’ [as] a singular portrait” and creates a moving story full of evocative images and sensations; just when the reader feels as if they understand that singular portrait, he takes away that feeling in the final line by refusing to represent anything. The poem is long and sprawling, stretching over several pages; it is supposed to illuminate the problem of homelessness with understanding—but the real point is you, the reader, don’t understand and can never understand. Kay Ulanday Barrett does the same with “YOU are SO Brave” when they reprint several things that have been said to them about their disability using many fonts and in several long paragraphs. By submerging the reader in the experience, it’s an attempt at understanding—but the body, and the body’s experience, always stands in the way.

While these tactics may seem to deliberately push away the reader, I was drawn in—perhaps because so many of the writers evoke the language of home. As Awkward-Rich notes in his conversation with Melt, home is a common motif in trans writing, one that is often transformed into a surgical story of magical apotheosis (or braveness). But for these poets, home is explored and rearranged without surgery, launched into space (by beyza ozer), found in trains (Awkward-Rich), or applied to a re-imagined Chicago (Ulanday Barrett). Home can be found in this work, not just because the authors have imprinted their longing and nostalgia in poetry, but because their work turns toward the community that came before them—and, hopefully, will come after.

In the introduction, Melt describes Subject to Change as a work inspired by a queer dance party—but a dance party that will eventually end. There is a heavy feeling in this introduction, especially as the image of the Pulse nightclub shooting is referenced in several subsequent poems. It seems especially difficult to write poetry in this time period, and indeed, that is Melt’s major concern in many of the interviews afterwards; Espinoza talks directly about Trump’s impact. Poetry may not save the day, Melt knows, but it does get people dancing. It does get movement happening. I think that movement forward, toward a home that has yet to be created, is the real point of the collection. Anything to get us beyond the bad poetry of our current state is going in the right direction.

H. Melt, Subject to Change: Trans Poetry and Conversation (Sibling Rivalry Press, 2017). 6×9, perfect bound, 110pp. US$17

Evelyn Deshane has appeared in The Atlantic, Briarpatch magazine, and Bitch magazine. Evelyn (pron. Eve-a-lyn) received an MA from Trent University and is currently completing a PhD at the University of Waterloo. Their latest project, #Trans, is an edited collection about transgender and nonbinary identity online. Follow @evelyndeshane for info.