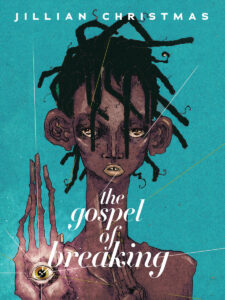

Jillian Christmas, The Gospel of Breaking (Arsenal Pulp Press, 2020), 80 pp., $14.95.

The opening line of Jillian Christmas’ new collection The Gospel of Breaking reads: “tell me what is a body.” This line can be read a few ways—I read it as a question or a plea. The next line branches into qualifications for this question:

tell me what is a body

of thought of work politic

practice how many vessels

gather together around one soul

and what is each holding

and how will we know them

to call them by their names[.]

As the collection’s first poem, “a home I can only leave once” situates the collection within conversations of labour and politics, but the poems that follow also present different understandings of the Black body: the Black body as garden, as a space of Black joy, and as a self-aware source of “unassuming magic,” as Christmas writes in her poem “soft-bellied beast.”

The Gospel of Breaking does not section or group its poems with any indexable markers. Instead, the form and shading of the poems places each in conversation with others in the book. Poems with titles in parentheses are in lower case, except for “I” pronouns, and they introduce the speaker’s mother, sometimes in past-tense recollections and other times in present-tense vignettes. The prose form of these parenthetical poems invites us to read the speaker’s familial relationships in first-person—to dive into these recollections as if they were our own and to see “the clever compromises of [the] heart,” in tricky family dynamics. Other poems are marked by lighter shading or right and left side margins. Some of the longer poems are divided into numbered sections using lowercase roman numerals. In all but one long poem, the numerals only reach ‘iii’ which feels like an assertion of the speaker’s presence, saying: I am here, if you haven’t understood by my third iteration of “I”, perhaps you are not paying attention.

In “sugar plum” the speaker confesses, “I have a tough time telling the difference between truth and myth,” which should perhaps give a reader pause as we wonder if we are simply being told stories, but in the end, the craft and skill of Christmas’ poems makes the distinction between truth and myth matter less and less. I am simply along for the ride, experiencing “the feeling of falling in love while in love” with Christmas’ poems.

One of the most memorable poems in the collection is “things I can do (for Sylvia)” where the speaker describes the experience of being a caregiver for a loved one in the hospital without clinical or sanitized language. As the title suggests, the poem consists of things the speaker can do to alleviate their companion’s pain and suffering:

I can brush your hair, squeeze

this tube of medicated moisture

onto green sponge

and through your open mouth.

I can run my oiled fingertips

across your dried lips,hold your hand, I can still hold

your hands. I can file and paint

your nails same as always, I can

play you all the sad song I know

on ukulele, I surprise myself,

I can pray.

For me, it is the tenderness and physicality of these lines that make this poem impactful and memorable, especially in a time of reduced physical and social contact.

The poems in The Gospel of Breaking are tender. They invite a reader to tend to themselves like “one sweet plump strange girl learning to tend to herself,” and to tend to their loved ones, but the poems are not soft. At times they are bitingly funny, such as “the bike poem” where the speaker’s bike is stolen while they are sick with the flu: “I pray it is perpetually kicking you in the crotch/ seriously what kind of asshat steals a sick person’s/ bike I imagine you are some depraved creature the likes/ of which would make hunter s. thompson’s skin crawl.” The speaker ends the poem with the line “I swear on lance armstrong’s/ good nut that when I find you/ I will have my revenge.” Poems such as this are a respite for the reader and a reminder that Christmas’ impeccable and unforgettable voice is the one guiding us through this collection, whether she writes about depression, trauma, or Lance Armstrong’s good nut.

The Gospel of Breaking asks us to consider what lies beneath each poem and its imagery as Christmas “[makes] closets into coffins” and tells us stories, shifting her voice to serve different purposes. In one of my favourite poems, “they said we wouldn’t need these life jackets on dry land,” the speaker reminds us that “the remedy is loving each other harder,” which is a remedy we would do well to remember.

Amy LeBlanc is an MA student in English Literature and creative writing at the University of Calgary and Managing Editor at filling Station magazine. Amy’s debut poetry collection, I know something you don’t know, was published with Gordon Hill Press in March 2020 and is a finalist for the Stephan G. Stephansson Award for Poetry. Her novella Unlocking will be published by the UCalgary Press in their Brave and Brilliant Series in 2021. Her work has appeared in Room, PRISM International, and the Literary Review of Canada among others. Amy’s next chapbook, Undead Juliet at the Museum, is forthcoming with ZED Press in spring 2021. She is a recipient of the 2020 Lieutenant Governor of Alberta Emerging Artist Award and will be starting her PhD in English in the fall.

Amy LeBlanc is an MA student in English Literature and creative writing at the University of Calgary and Managing Editor at filling Station magazine. Amy’s debut poetry collection, I know something you don’t know, was published with Gordon Hill Press in March 2020 and is a finalist for the Stephan G. Stephansson Award for Poetry. Her novella Unlocking will be published by the UCalgary Press in their Brave and Brilliant Series in 2021. Her work has appeared in Room, PRISM International, and the Literary Review of Canada among others. Amy’s next chapbook, Undead Juliet at the Museum, is forthcoming with ZED Press in spring 2021. She is a recipient of the 2020 Lieutenant Governor of Alberta Emerging Artist Award and will be starting her PhD in English in the fall.