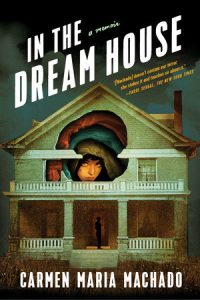

Carmen Maria Machado, In the Dream House (Strange Light, 2019), 264 pp., $24.95.

Carmen Maria Machado’s In the Dream House is a hybrid memoir that combines the author’s personal experience of queer domestic abuse with reflections on genre, literature, film, and identity. Within this criss-crossing of forms, memory is constructed as a Stepford-like “dream house”: a glossy exterior that hides sinister interior mechanics. The book’s structure is formed by repetition with difference. Each chapter is titled “Dream House as” with varying appendages, usually a genre, motif, or trope. Machado asks us to imagine her experience and observations through these different lenses, refracting the eponymous dream house as “Fantasy” or “Lesbian Pulp Novel” or “Pathetic Fallacy” or “apocalypse.” These connections link Machado’s own specific story to a larger assemblage of citations. The result is a rigorous use of intertextuality to excavate the author’s “dungeon of memory” (72).

Short, scalding chapters flash by quickly until moments where the reader is directly addressed. In one pivotal sequence, “Dream House as Choose Your Own Adventure,” the reader is suddenly jarred by a short blurb of text hovering on a blank page:

You shouldn’t be on this page. There’s no way to get here from the choices given to you. You flipped here because you got sick of the cycle. You wanted to get out. You’re smarter than me. (167)

Being where one shouldn’t is a tension that perpetually tugs at Machado’s reader. Such direct addresses dispel the notion that reading personal histories is ever passive in nature. In fact, In the Dream House frames reading as an act of transgression: to begin the book is to cross a threshold into the author’s most intimate past. Early on, Machado goads us for the power dynamics this creates by imagining the possibility the reader might visit the “real” dream house, the home in Iowa that Machado inhabited with her ex-partner:

You could drive there in your own car and sit in front of that Dream House and try to imagine the things that happened inside. I wouldn’t recommend it. But you could. No one would stop you. (9)

Why would a reader ever consider committing such an egregious violation? By conjuring our necessary voyeurism to its most awful zenith, we are left with the type of destabilized, icky feelings usually produced through weird fiction. This is not a trite warning to proceed gently with the details of Machado’s most intimate past, but a reminder that—with this book—a fragile and precarious trust has been extended to us. Machado emphasizes that “places are never just places in a piece of writing…Setting is not inert” (72). To devour In the Dream House’s extraordinary prose is to ingest a complex, painful reality situated in real time and space, a concept the author repeatedly emphasizes through descriptions of the dream house as alive or breathing. As readers, we must actively choose how we receive and hold this animate story.

Machado describes the dream house as a bifurcated structure: a real place and the text itself. This conceptual fragmentation is echoed structurally through the book’s short chapters and frequent shifts between genre. Machado selectively engages critical theory—Derrida or José Esteban Muñoz—to critique the hierarchal constitution of archives. There’s always a ruling body evaluating the relevancy of archival entries, which slips into an inevitable gatekeeping. Instead of discarding the archives as purely hegemonic, however, Machado refocuses our attention to the holes in the system. Considering the patchy canon of material on lesbian domestic abuse, Machado compassionately analyzes why queer archives often omit documentation of queers acting badly. In the Dream House serves as document of abuse that enters into a larger archive, but it also functions as a personal archive in its own right, where narrative takes on the form of memory: a series of moments and observation quilted together and fermented by time.

Described in this way, In the Dream House’s essayistic structure sounds like the postmodern maneuver typical of much recent queer autotheory. If readers of experimental literature have grown weary of this form, they will be refreshed by the urgency of Machado’s prose. Maggie Nelson’s The Argonauts, for example, also fuses philosophy, art, and personal narrative. Yet while the meandering, diaristic in-betweenness of The Argonauts often withholds or obfuscates a more rigorous interrogation of the self, Machado’s voice and identity pulsate through In the Dream House. The book’s fragments—which span popular culture, historical accounts, queer theory, myth and folklore—demonstrate an imaginative range and produce a panoramic representation of Machado’s personality. Machado’s unique method of self-portraiture reminded me of painters like Artemisia Gentileschi, Leonora Carrington, or Frida Kahlo who represent themselves in surreal or allegorical scenes. By detaching themselves from naturalism, these artists evoke the self with greater clarity.

Machado’s writerly magic, established by her first collection Her Body and Other Parties, springs from her capacity to twist genre without seeking to elevate or subsume it within highbrow literariness. Machado’s passions include fanfiction, Star Trek, and Dante’s Peak. Her ruminations on fatness reclaim the stereotype of the fat nerd, rendering this collision of identity tender, generative, special, and exciting. One of the most devastating moments in the book is Machado’s account of a Halloween party she attended during her MFA. Machado describes getting dressed into costume as one of the Weeping Angels from Doctor Who—entities which “feed on the potential energy of the life no longer lived in the present”—while her partner walks through the house yelling at her (84). Throughout the text, Machado describes pop culture poetically like this, transforming the mainstream into the viscerally intimate. The generosity with which Machado embraces pop culture is more frequently found in fandom than in “literary” texts. This quality energizes In the Dream House. To be clear, it’s not simply that Machado takes popular texts seriously or with uncritical enthusiasm. Rather, In the Dream House celebrates how queer expression often takes the form of an intense connection to an expansive bricolage of contrasting works.

More than any other genre, In the Dream House connects with horror as the kaleidoscope through which Machado’s reflections are filtered. By doing so, she reinforces the longstanding and often unacknowledged relationship queer people have had with horror. In one of the book’s best and most surprising sections, “Dream House as Queer Villainy,” Machado defends her love of queer villains from Disney’s cartoonish iterations (Maleficent finally gets her due as a “power-dyke”) to art house cinema (Alain Guiraudie’s Stranger by the Lake). Machado is fascinated by the contradictions embodied by queer villains, “the problem and pleasure and audacity of them” (46). It may seem surprising that she devotes so much time to villains in what is largely an account of abusive maltreatment. She makes clear that she isn’t celebrating the reductive stereotypes often exaggerated by queer villains, where they’re reduced to stand-ins for de-humanizing fears about queer people. Rather, she finds freedom in the notion that “queer does not equal good or pure or right. It is simply a state of being—one subject to politics, to its own social forces, to larger narratives, to moral complexities of every kind” (48). She doesn’t endorse villainy nor is she looking to explain her ex’s behaviour from sympathetic angles. Instead, she sees the analysis of villains as part of a framework that understands queerness to be prismatic and queer relationships to be complex.

In the Dream House asks that readers visit a haunted structure. Machado often moves between first, second, or third person perspectives and addresses multiple audiences: herself, her reader, her ex. As readers, navigating these shifts is akin to the kind of whiplash experienced by characters in a horror film, jerkily attempting to orient themselves in the presence of a malignant spirit or traumatized ghost. In literature and film, the trope of the haunted house is scary not just because of its inversion of domestic pleasantness but because traces of vindictive spectres linger after exorcisms or follow inhabitants when they move. We’re never certain a ghost is gone and they can nearly always be brought back. For Machado, it’s “the memoir [as] an act of resurrection” (5). This is no lethargic zombification of the past. For readers, navigating In the Dream House’s labyrinthine folds becomes similar to circling the hallways in The Shining; gaining a seat at the vitriolic dinner table in Hereditary; or joining the suddenly map-less group in The Blair Witch Project who terrifyingly confront what they thought was fable. To Machado, penning this memoir might have been a ghostly reanimation. For the reader, it is akin to possession: a pained, intense haunting from which we can never quite detach ourselves.

Katherine Connell writes about film and culture. She is a staff writer for the feminist film journal Another Gaze. Her work has also been published in BlackFlash, Canadian Art, Cineaste (forthcoming), Little White Lies, MUBI Notebook, New Statesman, Reverse Shot, and Reel Honey. She is a programmer at Inside Out and serves on the board of directors at Pleasuredome.

Katherine Connell writes about film and culture. She is a staff writer for the feminist film journal Another Gaze. Her work has also been published in BlackFlash, Canadian Art, Cineaste (forthcoming), Little White Lies, MUBI Notebook, New Statesman, Reverse Shot, and Reel Honey. She is a programmer at Inside Out and serves on the board of directors at Pleasuredome.